at Length

Posts Tagged ‘art’

Somewhere on the Road to Nowhere: Double Negative

Sunday, September 17th, 2017

In 1969, a young former abstract expressionist decided he was done with painting, went out to the middle of nowhere, set off explosives that displaced 244,000 tons of rocks, and made two 30×50-foot trenches that contained nothing.

That artist, Michael Heizer, was not the only one to name this kind of action “art.” That same year, Dennis Oppenheim dragged a broom through the snow to make Gallery Transplant. Robert Smithson poured hot asphalt down a quarry in Rome. Agnes Denes buried poems in a rice field. Hans Haacke buried himself in a series of photos entitled, fittingly, Self-Burial. They shared a common moniker, if not entirely a common cause: they were artists who had moved out of the gallery and museum system to make what came to be known as land art.

In our hyper-contextualized world of the tagged and displayed, relying upon “nothing” and “nowhere” as aesthetic constructs seems near dead. But there was a moment in American art in the late 1960s and mid-1970s that powerfully championed ephemerality, communality, and anti-materialism. They arrived at these shared philosophies of process from varying aesthetics and professional trajectories. Heizer, for example, was the son of a famous anthropologist; his family had lived in the Nevada desert, where he created Double Negative, since the 1800s. As a child, he accompanied his father on field work which took them from centuries-old Native burial mounds to newer sites, scarred by commerce and munitions. Perhaps it was this wide-open range he was thinking of when he wrote: “The museums and collections are stuffed, the floors sagging, but the real space still exists.”1

There is plenty to rightfully critique about land art. With a few remarkable exceptions, it was an overwhelmingly male-centric enterprise, as morbidly aggressive as it was naïve about gestural nuance. I think those critiques stand even if we are attentive to the dangers of presentism, which I am. And of course, anti-materialism and capitalism often end up bedfellows: today, no one gets into Roden Crater without a hefty donation, and Dia didn’t buy Earth Room for a handful of beads. But it’s my sense that Double Negative remains in the true spirit of land art: it’s open to anyone with the resources to make the trek. So that’s what I did. I went to see Double Negative for myself.

*

What I’m most attracted to in land art is that it insists its work is not to make A Landscape, but thinks of itself as the landscape—a physical testament to the idea that one cannot own what Julian Myers calls “the dream of an elsewhere.”2 Ideally, it has no entrance fee and keeps no hours. At Double Negative, there aren’t even actual directions to guide intrepid visitors; instead there near inscrutable instructions, like “Go to the top of the mesa and turn left at the cattle guard.” No museum houses it; there’s no guard, no gift shop, no wall label, no guide. My destination would be in a space past No.

Double Negative lies at the city limits of Overton, Nevada. My husband and I wound up through the empty streets of well-maintained houses to crawl a vertiginous road, the width of a horse and the incline of a roller coaster. After a half mile, the car righted itself onto a spectacular piece of land called the Mormon Mesa.

Mesas are a characteristic landform of arid environments: weaker rocks wear away and stronger ones remain standing, creating a flat, high area that resembles a huge table. No one lives on Mormon Mesa. There is nothing there. The view is likely unchanged in ten thousand years. Above, white canvas clouds hang in perfect mounds. Below is the entrance to 149,000 acres of slow-moving desert tortoise, quick hissing snakes, and creosote bursage scrub. It is impossibly quiet, because the wind takes every word away.

Outside the car the heat feels like a judgment, and lands everywhere. Walking on the mesa feels like walking on a moonscape. It occurs to me that I had unconsciously dressed entirely in black, as if I really was in a museum. I feel completely absurd.

*

Heizer was trained as a painter, but land art made him a sculptor. Because however revolutionary a project the land artists thought they were creating, that’s what land art is: sculpture. This isn’t so much about the physicality of sculpture—paintings are physical objects, too—but about how the fundamental painterly tools of hue and perspective are replaced by the fundamentally sculptural values of dimension and time.

The art historian Rosalind Krauss calls sculpture a medium “at the juncture between stillness and motion, time arrested and time passing.”3 And an interest in time was primary to the aesthetic of land art, which wanted to be at once ephemeral and epic, mythic and remote. Like sculpture, it is body-centric. In her landmark book Passages in Modern Sculpture, Krauss describes works where “the viewer’s movement as he walks around . . . endows these works with dramatic time.” Modernist painting, for example, could disavow figuration, but sculpture could never exactly disentangle itself from human form because there was always the body of the viewer, walking around it.

To get closer to the point: land art acts as a bridge between sculpture and performance art; the body of work enlists the body of the viewer. Double Negative may be just as still as a Rodin, and, as with a Rodin, I have to bring myself to it—but “bringing myself to it” is a far more dramatic enterprise, and, when I’m there, I’m an even more performative element than I would be in a museum—searching for it, walking around it, getting stinking hot.

I squint. My husband is pointing to something that looks like a landslide.

“That’s it.”

“That? Really? How do you know it’s not just nature?”

“Nature doesn’t cut a hill twice to make perfect facing valleys.”

*

The first noticeable thing is that this is an art that cannot be encompassed completely. I can’t back up far enough to take it all in. The only way to see the matching trenches and their valley in its entirety would be if I was that hawk over there making lazy circles over our head. In a sense, Double Negative can’t be seen at all.

We scramble down into one of the trenches. It’s been over four decades since Heizer made this work. Now, rubble fills sections of the shallows and wind has worn away the precision. Photos can show the size and placement but not the scent and texture of the work. Not the wind, and stillness; the heat and shadow. It is experiential; I exist inside and outside the work in an extraordinary position. I expected it to be a sensation, a question, of scale and grandeur; instead, I have an odd feeling of closeness, as though, out in this vast and indifferent beauty, I’m contained at the center of one person.

That’s a strange tension: land art meant to do away with the individual ego. Heizer’s monographer Germano Celant said that land art particularly eschewed the “narcissistic protagonism of the individual” abstract expressionism, among other forms, privileged and championed.4

Heizer and some of his compatriots felt they were in pursuit of a so-called genuinely American art form that would be democratic in its materials and universal in its methods. They rejected the modernists’ cult of personality by, among other things, demoting the whole criteria of skill. Donatello brilliantly sculpted David, but anyone who could pick up some rocks could make their own jetty. If we define the artist as a mark-maker, then land art thinks that lightning, water, the sun, the forces of entropy are artists.

*

We walked around in Double Negative for at most an hour. It was wonderfully strange to have nothing to touch—or, to put it another way, to be able to touch anything I liked. I threw rocks. I kicked dirt. I closed my eyes and baked in the sun. Yet I also believe I did Double Negative wrong.

I know that sounds strange. Art is not benign; it contains multitudes that include ideas of right and wrong. What was the point? That nothing had stuck to me and I had been nowhere?

When I walk the corridors of a museum I feel the conversation of history, but most land art is one remote work with nothing else in sight: the conversation has been silenced. In some ways, as much as I’m drawn to the ideals of land art, I felt I had been walking an empty grave.

My sense of my own wrongness found a kind of an answer this year when I went to visit a different piece of land art: Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels. A curator at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, which owns the work, gave me advice about best ways to reach the site—the museum–non-museum distinction as well as the stricture on instruction, it turns out, are not as stark as I or land art always want it to be—and said to me, “You should stay as long as you can. Nancy meant people to engage.”

The Sun Tunnels are spectacularly durational. The longer you are in them, the more you see. To lie in the tunnels is to be informed about the frame of nature, the movement of nature and yourself, your own nature. Did Double Negative not invite this? Or did I just not recognize its invitation?

What kind of invitation lies beyond No?

—–

Merridawn Duckler is a poet and playwright from Portland, Oregon, recently in the Wigleaf Top 50 for work in The Offing. Her art essays have appeared in Ekphrastic Review, Contact Quarterly, “Adventures in Dance” (University Press of Florida), and Nerve Lantern. She was a finalist for the Sozoplo Fiction Fellowship and in non-fiction at Writers@Work. Her fellowships and awards include Yaddo, NEA, SLS in St. Petersburg, the Norman Mailer Center, and the Berta Anolic Fellowship in Jerusalem. She’s an editor at Narrative and the international philosophy journal Evental Aesthetics. Her text-based work at Blackfish Gallery includes a hand-reproduced version of Walter Benjamin’s “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.”

—–

1. Michael Heizer, “The Art of Michael Heizer,” Artforum, December 1969.↩

2. Philipp Kaiser and Miwon Kwon, “Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974” (Prestel Publishing, 2012).↩

3. Rosalind Krauss, “Passages in Modern Sculpture” (The Viking Press, 1977).↩

4. Germano Celant, “Michael Heizer” (Foundazione Prada, 1997).↩

—–

All photographs are the personal photography of the author.

Tags: art, Double Negative, land art, Merridawn Duckler, Michael Heizer, Nancy Holt, nature, sculpture, Sun Tunnels

Posted in Art | No Comments »

The Colossal: Iris van Herpen and Girls Write the Museum

Tuesday, July 25th, 2017

As we enter the workshop room, three girls hover in a slow-motion game of musical chairs. The movement is familiar to me. Commit to a seat too early and there may not be enough seats for your friends, or you may be stuck next to someone who talks too much, or not enough, or otherwise fails to understand—at least, in the same way that you do—the unstated, byzantine codes of teen-hood.

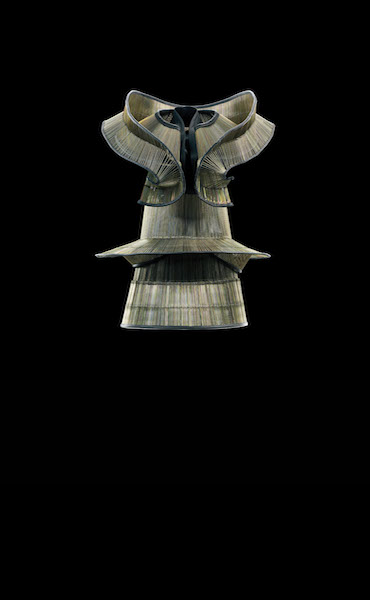

We’re at the Carnegie Museum of Art and have just viewed the Iris van Herpen exhibit, Transforming Fashion, which brings together seven years of van Herpen’s original haute couture. The poetry workshop is organized by Girls Write Pittsburgh, a nonprofit dedicated to empowering girls through writing. Our aim today is to write in response to van Herpen’s designs.

We sit around a long oak table surrounded by floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. The girls range from first to eleventh grade. Each says what they like to write—slam poetry, argumentative essays, short stories. One is a visual artist. Another plays the bells in the school band. It turns out the hoverers go to school together; the other four attend schools scattered across the city. They all seem focused, ready to work. The quietest one runs her fingers over her journal and looks at me, waiting for instructions.

*

I know little about fashion. My wardrobe consists of Toms, jeans, and t-shirts. I’ll focus on the poetry, I think. The words. But as I’m planning the workshop, I read up on van Herpen and become intrigued by her designs. I learn that early in her career, while interning for Alexander McQueen, she was required to do a variety of handwork, including beading and embroidery. Van Herpen says about that time, “I realized that an idea can come from a process of making. While doing handwork there, I had lots of ideas and got restless. I was dying to work for myself again. But it was really good to train myself to have that patience.”1

Van Herpen’s language about the “process of making” reminds me of being forced to write a sestina or a sonnet. As a writer and teacher, I’m continually trying to learn patience. I’m still no good at rhyming couplets, or obeying the sestina’s strict pattern of repetition, the way you have to pull out a word like a stitch again and again to come in at a cleaner angle.

*

As we enter the heavy gallery doors, our docent talks loudly, all business, and keeps waving to us, “Come closer. Closer.” Her bangs are curled under tightly, a brown inverted wave. Her posture, perfectly erect.

Down the expansive marble room stand two straight rows of bald mannequins. Each strikes the same pose—one foot an inch in front of the other, arms hanging down at the side, a slight bend at the elbow. The first collection, “Refinery Smoke,” is inspired by industrial smoke emitted by refineries. I call them the “cloud skirts.” Nutmeg brown cumulus clouds, they are made of metal gauze. A wide cloud formation hugs one mannequin’s hips. Another cloud hovers around her neighbor’s neck, obscuring her face. If you look closely, you see a fine latticework of threads, hard metal masquerading as a downy puffball.

One of the girls crosses her arms over her chest, says to her friend, “How could you sit in that skirt?”

I think of the ending of May Swenson‘s poem, “Question”:2

How will it be

to lie in the sky

without roof or door

and wind for an eyeWith cloud for shift

how will I hide?

The docent shifts her stance, and stares directly at us. “Iris van Herpen was trained as a dancer. This gives her special insight into how the body moves.” The girls seem impressed when she lists some of van Herpen’s clients: “Björk, Tilda Swinton, Lady Gaga.” She adds “Beyoncé” as an afterthought, and a few girls open their mouths and look more intently at the dresses. When asked by an interviewer, “Who buys and wears your clothes?” van Herpen responded, “People who see clothes in a different way.”

*

We move on to the “Skeleton Dress.” “Has anyone ever jumped out of a plane? Gone skydiving?” the docent asks. Nobody says anything; we just glance around at each other stiffly.

Van Herpen’s skydiving experiences inspired her “Capriole” collection. The dress that represents her racing thoughts before jumping resembles a jumble of thick black snakes. My personal nightmare, it’s a dress Björk wore with a big smile on her face. Van Herpen says of the dress, “It visualizes the extreme energy I feel during the one minute free-fall, where I become strangely aware of the inside of my body.”3

My co-workshop leader, Laurie, whispers to me, “It’s like she’s making visible the things we drag around all the time. Putting on the outside what’s inside.”

One of the girls stands in front of a black leather dress that looks like it was pushed out of a pastry bag. Black waves of icing snake up and down the A-line dress in maze patterns. She leans in close, her nose almost touching the leather.

Installation view, Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion at Carnegie Museum of Art. Photo: Bryan Conley

Installation view, Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion at Carnegie Museum of Art. Photo: Bryan Conley

Iris van Herpen, “Radiation Invasion, Dress,” September 2009, Faux leather, gold foil, cotton, and tulle, Groninger Museum, 2012.0201. Photo: Bart Oomes, No 6 Studios

The “Radiation Invasion” collection has the slick look of oil—the dresses alluring and sinister, what Bellatrix Lestrange might wear to drink her morning tea. The designs are based on the radiation that surrounds us, alpha, beta, gamma, x-ray, and neutron waves. Van Herpen imagined what would happen if we could manipulate these waves in the future. “What if our bodies could attract and repel as living magnets?” reads the description I find online.

One of these dresses has a mask that covers the mannequin’s face with silver leather interlaced into a stack of shimmering V shapes. “The dresses are made for model’s bodies. Very slim,” says the docent. I wonder how the girls register this comment. Their faces are impassive.

*

How to say in language what van Herpen’s dresses do? I can feel my words touching the textures and shapes of her dresses, but the whole of them make an experience words can grope, but fail to hold. For me, each dress functions the way a poem does: “A poem should not mean / But be.”4

Van Herpen allows the material she’s working with to help dictate the form. “It’s my direct action with the material that often is my design process,” she says. “Each technique and each material asks for another approach and process, and that’s what challenges me, to find new ways of thinking and doing.”5

For writers, words are our sole material. But in the process of ekphrasis, a verbal description of a visual work of art, the visual can be a springboard to new language. Ekphrasis creates something separate but connected, not entirely a new thing, but one charged with the force of the new.

Art can give us a new space to move our thoughts around in, an unfamiliar space in which to imagine standing. It’s especially necessary for young people. I remember my own teenage years—the sudden feeling of options narrowing. I wouldn’t be an Olympic soccer player, or an astronaut. Walls rising up around me. Those walls already felt gendered: I could like sports but should also be pretty; I could be smart, but not outspoken. Some things made me feel free: books, music, nature, art. Art offers us permission to expand. To be uncontainable.

*

Van Herpen’s work, which is in a form that is at least imagined as capable of containing people, feels colossal. It reaches beyond—not only language, but also our usual understanding of physical reality, what the materials of our world can do.

To make the “Chemical Crows” collection, van Herpen and her team took apart 700 children’s umbrellas. I’m drawn to a dress that has wings made of brass umbrella ribs arcing above the shoulders. I want to run my fingers over each brass rib.

Iris van Herpen, “Chemical Crows,” Dress, Collar, January 2008, Ribs of children’s umbrellas and cow leather, Groninger Museum, 2012.0192.a-b. Photo: Bart Oomes, No 6 Studios

Installation view, Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion at Carnegie Museum of Art. Photo: Bryan Conley

One dress has hundreds of ribs fanning out in a tall, regal collar. I’d like to wear it on a day when I don’t want to talk to anyone. A few of the girls whisper something about warriors. I hear them saying, “Cool, cool.”

*

Van Herpen’s “Bird Dress” has seagull skulls nested in it, made to look like live birds, with fierce eyes and open mouths. One looks about to bite the mannequin’s pallid neck. Some girls seem impressed by this fact, others grossed out. Van Herpen said of this dress, “There are 3 birds that are fighting together and trying to fly off. The dragon-skin feathers move completely differently from normal feathers. They vibrate in all directions when you wear the dress, which creates a strange optical illusion when looking at the birds in motion. I tried to visualize the surreal movement between man and nature here. The dress looks technical, but is completely handmade.”6

My favorite dress looks like an organ in a European cathedral, and also like something Artemis would wear on the hunt. It’s made of magiflex, a plastic used in the sign industry—the dress is at once rigid, intricate, and earthy. I hover near it awhile, wishing I could try it on. Maybe I wore this dress in another life.

My notes tumble into a list of oppositions that later seem beside the point: technical/handmade; soft/hard; wood/plastic; process/product; utility/beauty.

*

In the workshop room after viewing the exhibit, we ask the girls to take a few minutes and look through their notes.

“What words or thoughts interest you? Underline them if you want,” I say.

Someone asks, “What is the point of creating clothes that aren’t accessible to real, everyday people?”

“It’s about expression and experimenting.”

Another girl says, “Yeah, it’s fashion as an art form.”

“But why can’t she make it more open for normal people to wear?”

I thought the girls would be interested in writing into their imaginations—naming superpowers, or science fiction flights of fancy—instead of wanting something for normal people to wear. I think of my eleventh-grade English teacher, Dr. Brozick, standing at the chalkboard next to the scrawled question, “What is normal?” He had nipple rings that poked through his shirt, and supposedly rode his motorcycle cross-country to go whale watching in California every summer. I loved him and I feared him.

I can’t remember anything more than the question—and what it did to me. It was the first time I saw that word. “Normal.” I started looking at people differently, wondering why I bought clothes at the Gap, or hadn’t dyed my hair green. But I think by the word “normal” the girls mean a dress they can wear in everyday life. Something that is of use.

Gaga and van Herpen would agree that there is no normal. Yet the dominant tide of our culture still pulls us all toward a milquetoast middle ground.

Marianne Moore argues that in poetry, we find:7

Hands that can grasp, eyes

that can dilate, hair that can rise

if it must, these things are important not because ahigh-sounding interpretation can be put upon them but because

they are

useful; when they become so derivative as to become

unintelligible, the

same thing may be said for all of us—that we

do not admire what

we cannot understand.

Van Herpen would have us live in Moore’s “imaginary gardens with real toads in them.” And, I think this is what the girls want: some sense of a colossal world in which the ordinary can also live, as well as the reverse—the colossal in the everyday.

Installation views, Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion at Carnegie Museum of Art. Photo: Bryan Conley

Our first writing prompt uses the beginning of Lucille Clifton’s poem “it was a dream.”8

in which my greater self

rose up before me

accusing me of my life

The handout reads, “What does your greater self or fiercer self look like, sound like, act like? What does she say?”

Like the girls interrogating van Herpen’s dresses, I sometimes wonder, what is the use of art and poetry, of one workshop on a Sunday afternoon in April?

We write for a while to the prompt, and share with the person next to us. The girl next to me shares her poem. I have to lean in to hear her voice. She reads about how her best self, her fiercest self, walks down the street with pride. Holds her head high. It’s a concise, powerful lyric poem. She’s only in seventh grade. But she doesn’t leave her contact email, so I can’t reach out to ask for the poem. I keep trying to remember the words. I can see them in neat printing on the lined page of her journal.

*

I wish I’d had a workshop like this when I was their age. I was writing alone, not sharing with anyone. It took me twenty years to write a poem about being harassed by the boy who sat behind me in eighth grade homeroom. He would lean up every morning and whisper things in my ear while I was trying to finish my homework. Things like, “You have such a nice ass” or “I know you’re actually a slut.” My spine froze. I pretended I didn’t hear him. I wish I had been able to write about it and share it with someone who might have understood. I wish I could have imagined being protected by the Artemis dress. His knife-like words bouncing off my body like tiny leaves.

*

One of the older girls, Sophie, shares her poem. We all listen, then comment on parts we liked. One of the girls says, “I liked how you said you felt inhuman. That felt powerful to me.”

Sophie later says she’d love for me to include it in my essay. Here’s an excerpt:

Freedom

I’ve always felt like I don’t belong.

I’m not referring to feeling isolated from people. I’m not referencing the idea of being a unique and “weird” individual. What I am trying to convey is much less earthly and far darker than anything human.

I feel inhuman.

I feel like my body is not mine at all. I feel like an outsider in this sphere that we call our world. I feel like I am not a person. I truly feel like life was not meant for me.

And I’ve felt this way since I had the ability to form and remember thoughts.

I feel like I’m an invisible gas just floating about, with nothing but thoughts to call my own.

But I AM human. I DO live in a body. It’s mine. I have eyes and a brain and muscles and skin. I live and experience the earthly life.

—Sophie Williams

We’re out of time, so we give the girls a prompt to take with them: Pretend you are writing a letter to yourself. What do you want to say? You might think about the van Herpen dress you found most striking. What about it compels you? What makes you feel free?

If you get stuck, try what Jan Beatty does in her poem, “I’ll Write the Girl.” Name what you’ll never write, then write what you will.9

The thing I’ll never write is the green leaf

with its rubbery-hard veins, I’ll never

write the structure exposed, insteadI’ll write the girl picking it up, green leaf,

her pudgy hand & her wanting it, that’s it

—–

Emily Mohn-Slate‘s recent work is forthcoming or has appeared in New Ohio Review, Crab Orchard Review, Indiana Review, Tupelo Quarterly, Poet Lore, and elsewhere. Her manuscript, The Falls, was a finalist for the 2016 Agnes Lynch Starrett Prize offered by University of Pittsburgh Press, and the 2017 Blue Light Book Prize offered by Indiana University Press/Indiana Review. She teaches creative writing at Chatham University and lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

—–

1. Alice Gregory, “Iris Van Herpen’s Intelligent Design,” The New York Times Style Magazine, April 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/08/t-magazine/iris-van-herpen-designer-interview.html.↩

2. May Swenson, “Question,” Nature: Poems Old and New (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1994).↩

3. Liz Stinson, “Iris van Herpen’s Extraordinary Clothes Are More Like Wearable Sculptures,” Wired, November 2015, https://www.wired.com/2015/11/iris-van-herpens-extraordinary-clothes-are-more-like-wearable-sculptures/.↩

4. Archibald MacLeish, “Ars Poetica,” Collected Poems 1917-1952 (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1952).↩

5. Stinson, “Iris van Herpen’s Extraordinary Clothes Are More Like Wearable Sculptures.”↩

6. Stinson, “Iris van Herpen’s Extraordinary Clothes Are More Like Wearable Sculptures.”↩

7. Marianne Moore, “Poetry,” Others for 1919: An Anthology of the New Verse, edited by Alfred Kreymborg (New York: N.L. Brown, 1920).↩

8. Lucille Clifton, “it was a dream,” The Book of Light (Copper Canyon Press, 1992).↩

9. Jan Beatty, “I’ll Write the Girl,” Red Sugar (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2008).↩

—–

Exhibition Credits, from Carnegie Museum of Art website. Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion was co-organized by the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, and the Groninger Museum, the Netherlands. The exhibition was curated by Sarah Schleuning, High Museum of Art, and Mark Wilson and Sue-an van der Zijpp, Groninger Museum. Support for this exhibition has generously been provided by Creative Industries Fund NL.

Tags: art, Emily Mohn-Slate, fashion, Girls Write the Museum, Iris van Herpen, poetry

Posted in Art | No Comments »

Four Paintings by Margarita Gokun

Wednesday, May 17th, 2017

Editor’s Note

In 1766, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing wrote a piece called Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry. In it, he famously described poetry as a temporal art and painting as a spatial one. Generations of scholars, critics, poets, and artists have complicated this since, of course, and some hold that neither temporality nor spatiality have much to do with either.

The occasion for Lessing’s essay is not a poem or a painting, but a sculpture, Ancient Greek, of the Trojan priest Laocoön. He tried to warn that the Trojan Horse was, indeed, a Trojan Horse, and for his trouble was besieged by god-sent serpents. (He had already angered the gods once, by breaking his celibacy.) The Trojans assumed, to their demise, that his fate meant that the Horse was safe. Laocoön’s sons, born of divinely-forbidden sex, gaze up from his serpent-twined body to look at his contorted face, and the ringlets of Laocoön’s hair look like tiny and vehement snakes themselves, a Medusa if Medusa’s beasts had turned on her rather than seem to leap to her defense, his head thrown back.

I started thinking of Laocoön again, sculpture and essay alike, when I joined At Length‘s staff, which made me start wondering how the art section might engage with the idea of being, well, at length. For all of both of their seeming certainty or legibility, both the sculpture and the essay are ekphrases, which, to me, entails an attempt at an impossible translation. The Laocoön sculptors tried to take a particular moment in a myth and transform it into a perpetual, concrete object. Lessing tried to transform various forms of art into a system of analysis. Both works are problems, not solutions, in the richest sense of the former word: a puzzle, a riddle, an enigmatic statement, as full of the unpredictable as the inside of a horse that, invisibly, contains an army.

“Length” is a versatile word: it’s a verb (as in lengthen) and a noun, and it’s about both space and time. And “at” is a shifty preposition: it can indicate a point at which things meet, as in, touching length; it can signal a place, or a time, or both; it changes in meaning when applied to different nouns, like, of course, to go on at length. Both words are ambiguous, particularly in terms of the kinds of relations they draw between various positions, persons, utterances, places. “At length,” too, is a problem. The pieces that intrigue me—both in terms of artwork itself and art writing—won’t try to solve the problem of the phrase “at length,” or any of the problems they find themselves encountering and engaging, but instead try to inhabit those puzzles, and crawl into the rich mysteries they present.

—Sumita Chakraborty, Art Editor

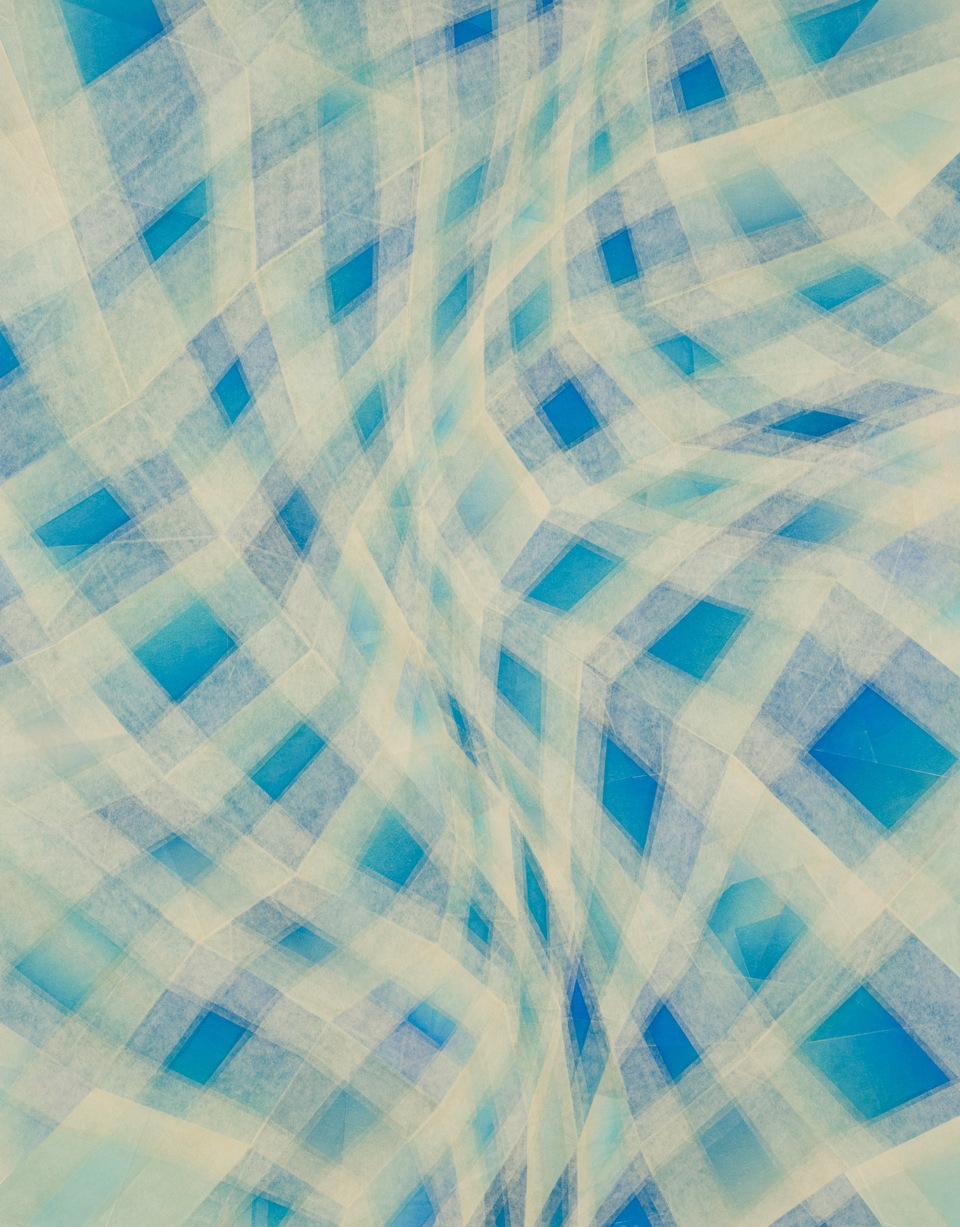

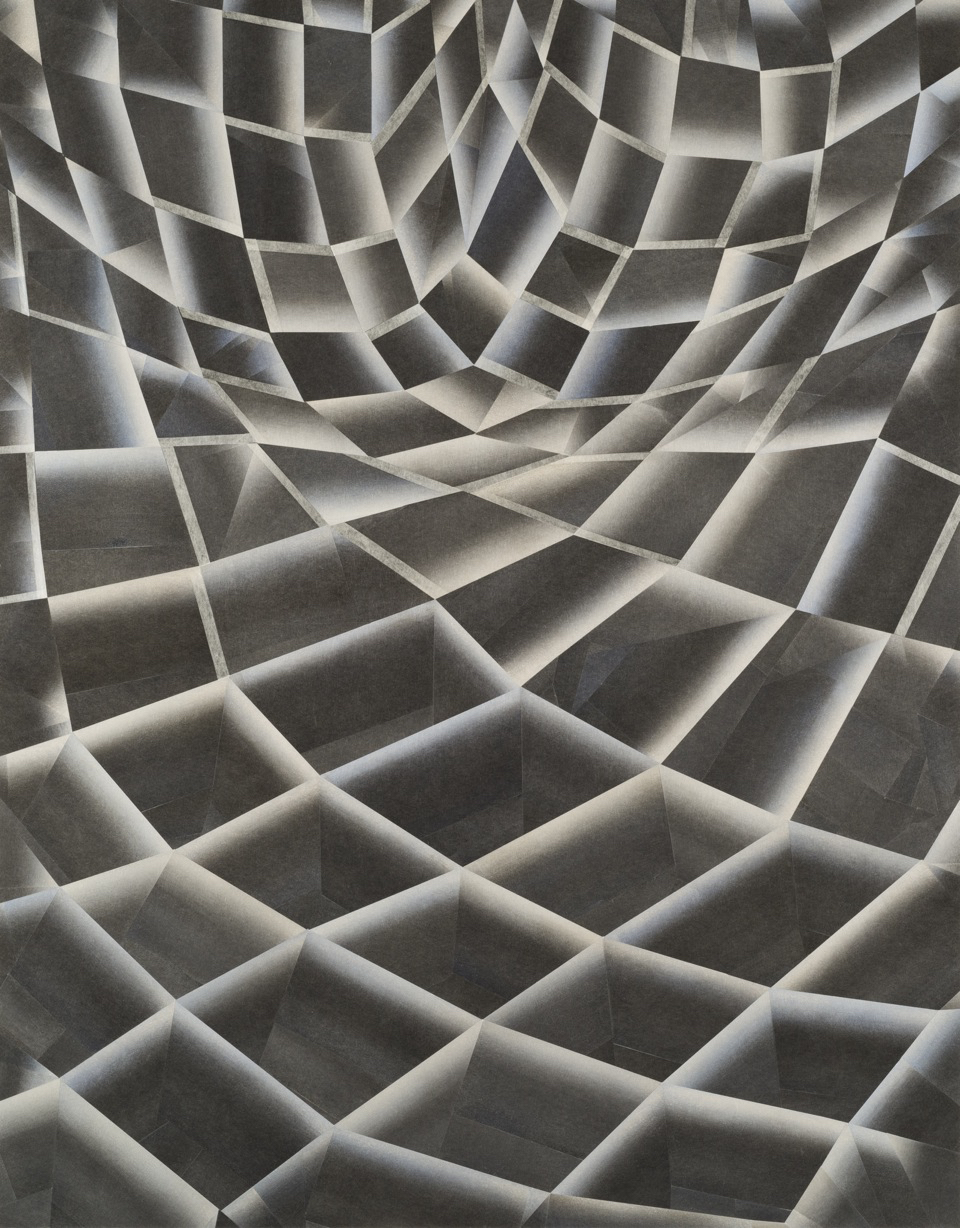

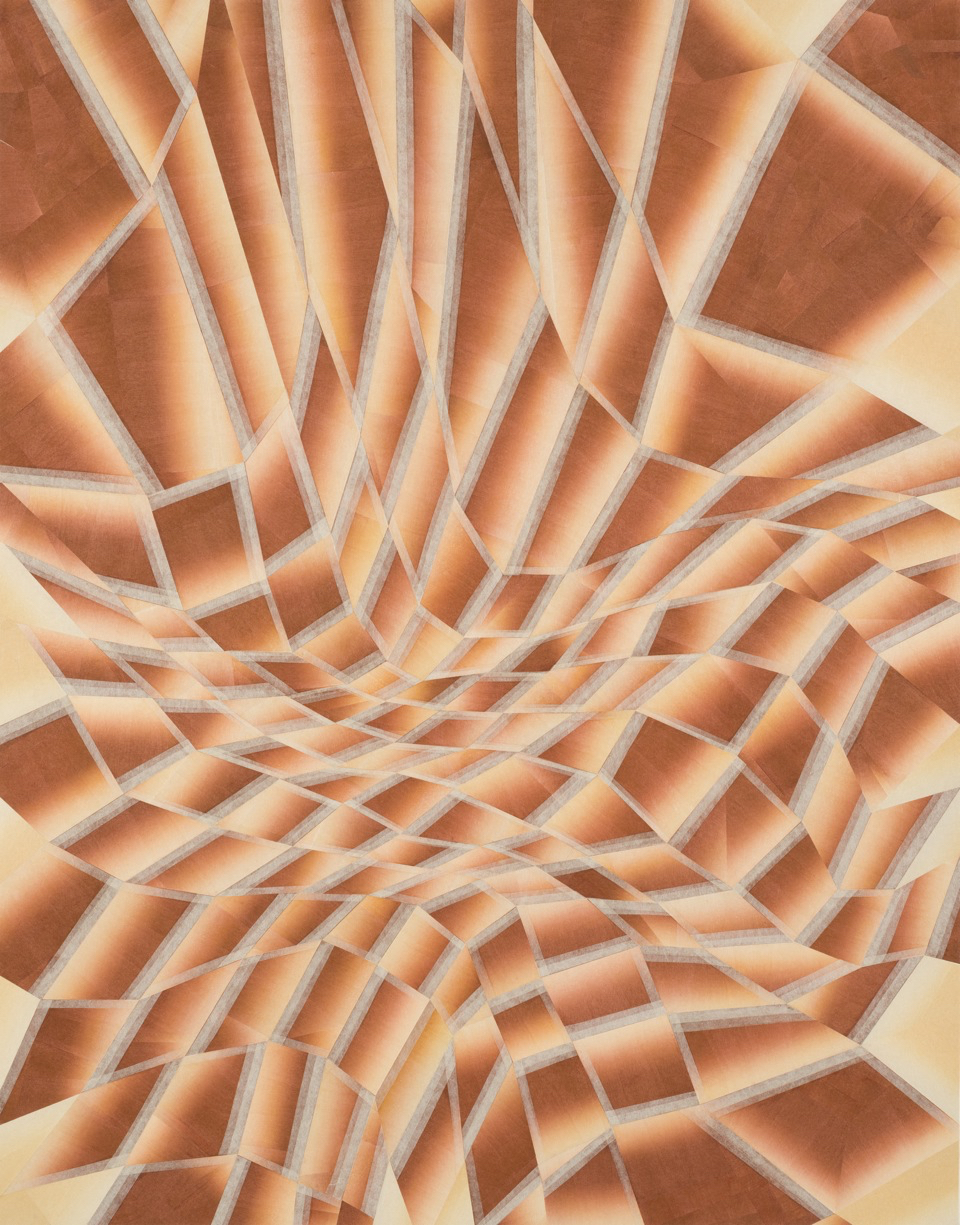

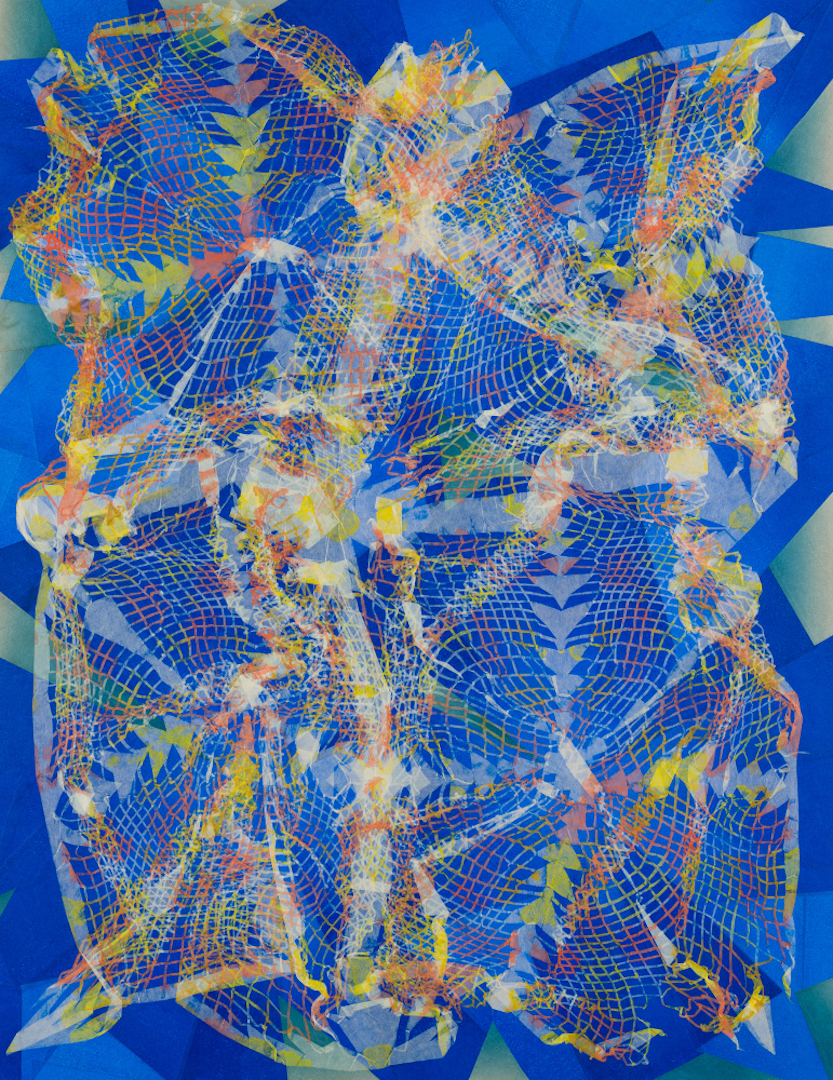

Birth of a Star, Light Travel, Blue Fog, and Orange Light:

Four Paintings by Margarita Gokun

To begin, I present four pieces by Margarita Gokun, a writer, novelist, and painter whose writing has appeared in The New York Times, the BBC, The Wall Street Journal, NPR, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, The Guardian, Smithsonian, Saveur, and elsewhere. Her paintings are currently a part of an ongoing exhibition at Casa Sefarad in Madrid, Spain. The exhibit, titled “In Spanglish,” features Gokun as well as two other American artists who are currently living in Spain.

Margarita gave me the option of selecting any of her pieces to feature in At Length; below you will find two pieces each from two of her series, “Thoughts” and “Experiences.” All four seem to me to take their titles, and the title of the series in which they are in, as provocations. All four imbue their uncertain lacunae with a kind of palpable, haunting, and enticing energy. All four give us just enough that we can discern to make us want to reside in what we do not.

Birth of a Star, mixed media on canvas, 50x60cm, 2010, “Thoughts” series

Light Travel, mixed media on wooden recycled wine boxes, 55x34cm each, 2016, “Thoughts” series

Blue Fog, oil on canvas, 33x43cm, 2011, “Experiences” series

Orange Light, mixed media on canvas, 50x60cm, 2012, “Experiences” series

Tags: art, Margarita Gokun, mixed media, painting

Posted in Art | No Comments »

Takuji Hamanaka

Monday, January 18th, 2016

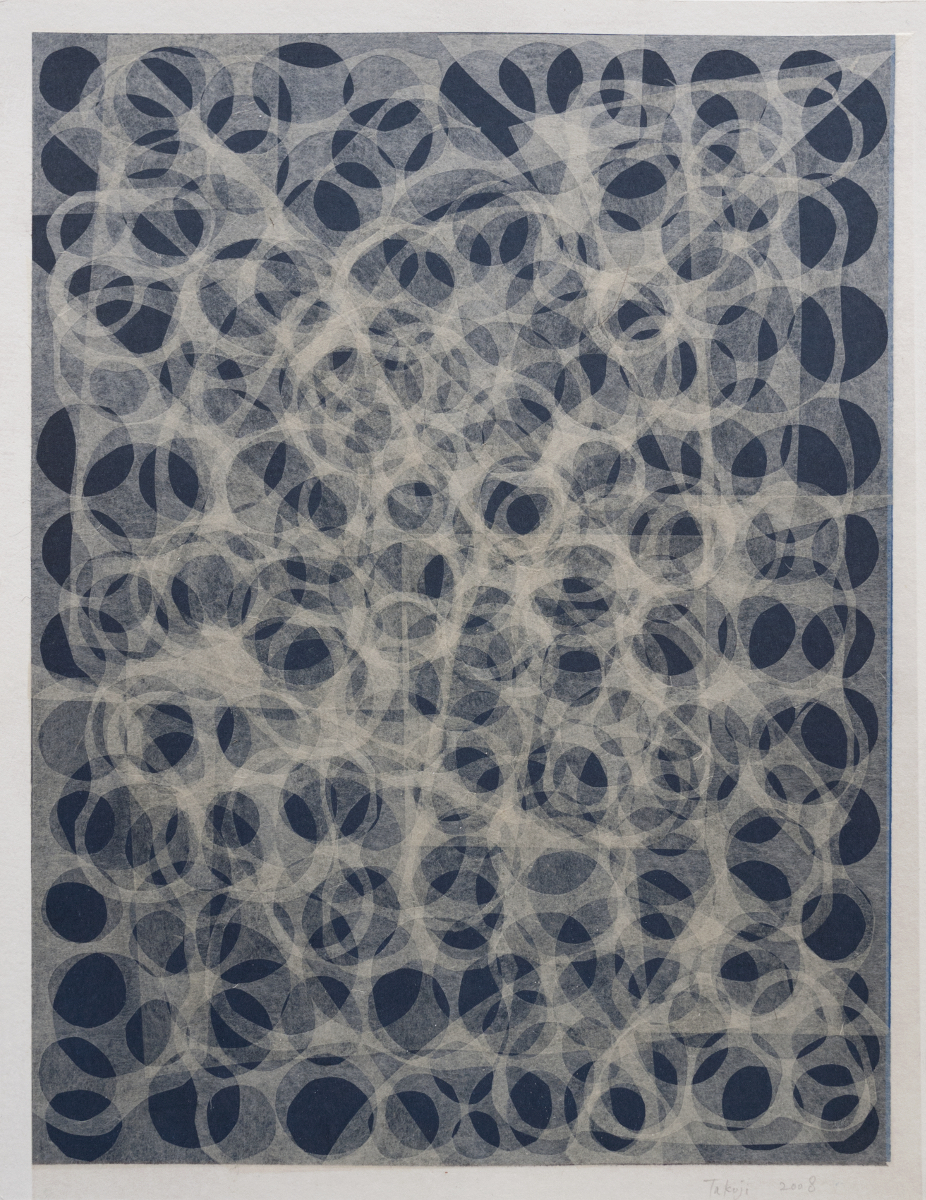

Negative Circle, 2008, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 12 3/4 x 9 7/8 inches. Image courtesy of Owen James Gallery.

In the spring of 2015, artist and printmaker Takuji Hamanaka taught an introductory workshop in Japanese woodblock printmaking at Penland School of Crafts in North Carolina. At Length‘s art editor-at-large, Elaine Bleakney, was a student in the workshop, and followed-up the experience by corresponding with Hamanaka about his painstaking inventions in process, including an extracurricular use of Japanese Gampi paper–an extremely light tissue familiar to printmakers.

At Length

I’m curious about your recent series of Gampi paper collages that alter the traditional Japanese woodblock printmaking method you have mastered. What inspired these works?

Takuji Hamanaka

It started out by a mess my mother made. In my parent’s apartment where I stay whenever I come back to Japan, there is shoji screen facing east. In the morning when the sun hits the paper on the screen, light transmits through paper, brightening the room without exposing what’s in the room to the outside.

One visit, I found a repair on the screen–a rather common occurrence you would find on a shoji screen. It turned out that my mother had broken a hole through the paper when she was vacuuming the floor. She had cut a small round piece of paper and glued it to hide the puncture. It’s something we would have seen much more back in the days when there were children in the household; you can imagine how fun it could be for a child to poke through paper with a stick or a finger. This thought was inspiring for me, maybe because I have spent many years now in a foreign land and I might have forgotten one of those typical images of daily life back home.

Once I came back to Brooklyn, I wondered if it would be possible to capture the effect I saw on my mother’s repaired screen. I started using a couple of different Japanese papers and experimented with paper-on-paper collage. They looked interesting but since I used plain paper there was no color and it was hard to see the layers unless I placed the collage by the window. After a couple of experiments with different papers and mixing this up with woodcut, I started using Gampi paper. I have known Gampi as used in the Chine-collé technique in etching and lithography. But I wanted my application of Gampi to be quite different from the way it is usually done.

Traditionally, Gampi is used at the receiving end of printing: its surface is fine and smooth so that an image on a plate or stone can be transferred to it much better than other heavier papers. What I do is use Gampi as a more active main component in image making. I cut a large number of papers, sometimes hundreds of them in different shapes, and repeatedly paste them on the woodcut.

Night, 2012, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 30 3/8 x 23 3/8 inches

TH

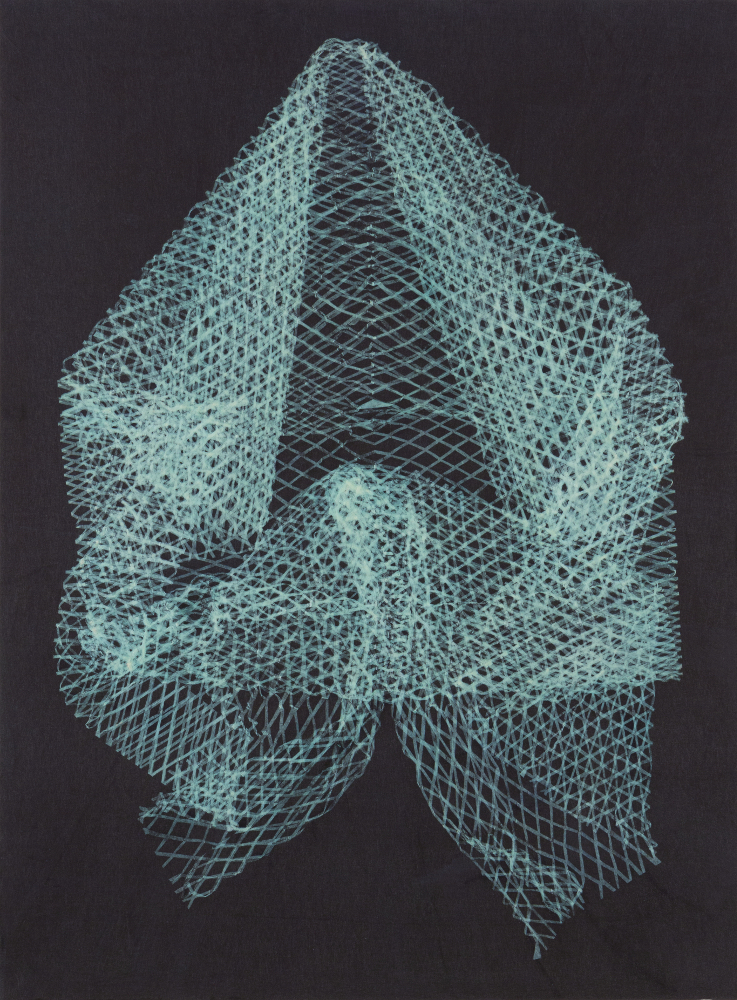

I like the translucency of Gampi paper and the effect I can achieve by layering. Once many layers of paper are pasted on the woodcut it attains a somewhat contradictory visual effect: in one sense it appears to be so flat because of nature of paper yet if you take microscopic point of view there are mountains and valleys of paper. It’s as if you’re looking down into clean and deep water, seeing from the surface to the bottom, capturing the distance between the peak and the depth. I also feel that repeatedly pasting paper after paper is like making a time recording device: time spent on one particular piece is visible and can be returned to even at the end of the process.

For the last several years I have been thinking about characteristic expressions or materials in printmaking and using them in an unconventional context or a context that I haven’t tried before. My use of Gampi is one example of this. Also, I exclude act of cutting wood, except for a base-color woodcut on which I build layers of shape.

Quiet Person, 2013, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 26 x 20 inches

AL

How long does one of the Gampi collages take? Do you find that–embarking on a technique with the paper that is unconventional–your errors also feel unconventional or surprising?

TH

Collage works takes so much time to complete. The paper itself is so thin and light that it requires extra care to handle/cut it in the shape I like, and in some of these works I cut hundreds of different-shaped papers, individually pasting them in one work.

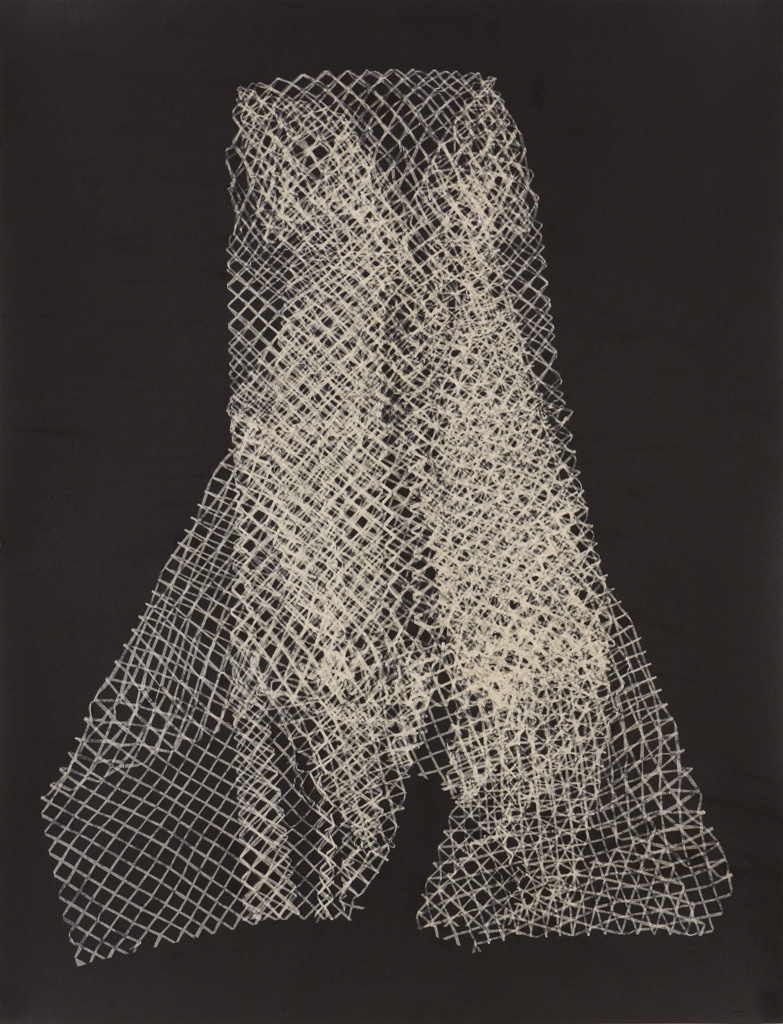

Sometimes I found that when I applied wet Gampi to print, it didn’t adhere in clean way and looked like bad wrinkled paper. This really disturbed me. I put aside those mistakes. But after a while I looked back and found potential to explore some other direction in my works. How what disturbed me became something interesting, I don’t know–but the more I looked at them the more I started to see differently. This is how I started cutting many grids on a sheet of Gampi, making a sort of paper lace and fold like Veil [shown below]. Error would happen often in a way that could be inspiring. Of course sometimes an error was just error and pissed me off!

Veil, 2013, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 26 x 20 inches

AL

The scene you speak of–your mother repairing the shoji screen–I’m wondering if you’ve told her that it inspired your current work?

TH

After I made a good chunk of collage works I did tell my mother how I got inspiration in the first place and she demanded some credit, only laughingly.

AL

Does it surprise you, looking back and through to the place where you have arrived in your work?

TH

I often think about using the characteristic expressions and materials of printmaking in different contexts. I guess you could call it ‘transplanting’ or ‘displacement.’ Putting familiar elements in unfamiliar places creates different meanings and that simple act really intrigues me.

AL

Did these acts of displacement feel like acts of bravado, at first, considering your years of formal training in traditional Japanese woodblock printmaking?

TH

It is true that I was trained in a very traditional printmaking style [at the Adachi Woodcut Print Studio in Tokyo] where they force you to you adhere to a set of values in visual sense, and the ways things should be done.

I appreciated that visual sense and respected it very much. I still do. But even when I was an apprentice I was aware how living in very restricted environment (traditional printmaking) affects your way of thinking. In a way it feels like a complete world where the rule is clear and the standard is set and you only need to achieve that, no more than that. That alone is not an easy task. But the limit is set. For me, making art is to break [a limit] and displacement helps me realize this.

In traditional printmaking, a clean beautiful finished surface of print is critical and you aim to achieve that. In contrast, I felt an urge to curve and mess up lines using a v-shaped gouge to make a print complete. This was against what I acquired at the shop and it was a very interesting moment for me. I understand to some people this might be nothing but for me it was a good step forward to making interesting works.

AL

Did your work on woodblock print editions for artists like Sol Lewitt and others encourage you in a more experimental direction?

TH

Having the opportunity to work on a Sol Lewitt print project [at Watanabe Studio in Brooklyn in the early 1990s] had educational meaning to me. I did not have much of a personal interaction with Lewitt but he was a very generous person. I not only looked through what he had done, but I also began looking at artists from the 1960s and 70s. The studio I worked for had lots of Lewitt books and also old editions of Artforum. I rediscovered many great works made by various artists then.

Whirlwind, 2015, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 32 x 25 inches

AL

We haven’t talked about your actual displacement–from Japan to living and working in New York City. Do you feel, looking at some of your recent work, that living in a large foreign city is something expressed in your works? In your prints Night and Negative Circle for example, I wonder if the energy in these patterns have any connection to living in a place where space is compressed or even claustrophobic at times.

TH

I have never thought about making a connection between my works and living in city. Do some of my works look urban to you, I wonder.

I am aware that it is good thing for me to stay away from NYC from time to time. Wherever you live I think it’s nice to step outside of your familiar environment and see it from another point of view, if you can.

One thing I can say I like about living in a big city is that I can be anonymous. This gives me a sense of freedom.

Shattering Echo, 2015, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 32 x 25 inches

AL

How do you experience the city geography? Do you walk often?

TH

I’ve enjoyed walking since I was young in Japan. On sunny days I used to walk to the nearest town to check out a bookstore and such. It was long walk, a little more than two hours round trip, but I enjoyed that. I did not enjoy using public transportation. I liked the private space I could maintain while walking.

I still prefer walking to riding a bicycle in my neighborhood here in Brooklyn. I like the speed of walking: no rush, not so fast.

AL

When you were young, what sorts of books did you enjoy looking at?

TH

When I was young I would go to various second-hand bookstores. I wasn’t a physically strong kid but I never seem to get tired when I was at a bookstore. I would search through piles of old book and magazines for hours. Mostly I was interested in literature and books about woodcut. I also liked the book as object, a beautiful cover design and text to read. These combined seemed to me a perfect medium.

Kasutera, 2015, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 32 x 25 inches

AL

There is something about color in your newer works, the layering of color and tones, that evoke interior emotional life to me. Do you have thoughts about color and your relationship to it?

TH

There had been a time where I could only work in black and white–for a long time. Generally my relationship with color wasn’t good, it was always difficult and I tended to minimize the use of color. But my very current works and a new series of works I hope to finish in a few months will be a departure. I am quietly excited about the possibility these new works embody.

Distorted Web, 2015, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 32 x 25 inches

Takuji Hamanaka presenting a slideshow of his work at Penland School of Crafts. Photograph by Elaine Bleakney.

Takuji Hamanaka is an artist and printmaker living in Brooklyn, New York. He apprenticed in traditional woodcut printmaking in Tokyo, Japan. In recent works he combines printmaking with collage, using extremely thin Japanese paper called Gampi. His work has been exhibited at the International Print Center, New York; Whitman College, Washington; National Academy of Fine Arts, India; and the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh, Scotland, among others. Takuji Hamanaka has received a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship, NY; KALA Art Institute Fellowship, CA and has been a resident at the MacDowell Colony, NH; Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, ME; and at Open Studios, Museum of Arts and Design, NY. He is represented by Owen James Gallery in NY.

Tags: art, collage, Elaine Bleakney, etching, Gampi paper, Japanese woodblock printmaking, Japanese woodcut, lithography, Penland School of Crafts, printmaking, Takuji Hamanaka, woodblock

Posted in Art | No Comments »