at Length

Posts Tagged ‘ClampArt’

Robert Calafiore

Thursday, June 28th, 2018

Robert Calafiore, interviewed by Debra Klomp Ching, about his extraordinary and colorful pinhole photographs.

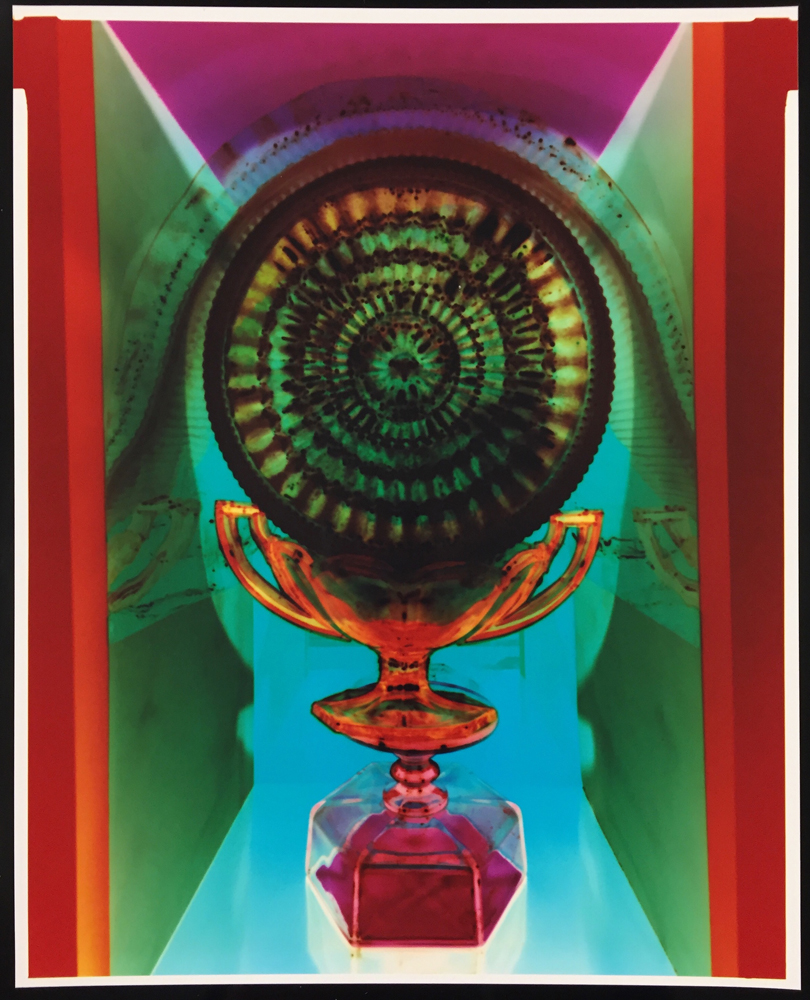

Still Life (2017-2018), 10″x8″ unique pinhole C-Type ©Robert Calafiore/courtesy ClampArt, New York

At Length: Your work was initially brought to my attention via your Instagram feed. How important is your social media presence to your creative practice?

Robert Calafiore: A very close artist friend of mine sat me down one day and said she wasn’t leaving my house until I did two things: build a website and open an Instagram account. I did both. I was excited about launching a website and worked for a few weeks to get the first version up and running. However, I was far more hesitant and nearly unwilling to begin a relationship with another social media app. I had read a great deal about the opportunities it might provide for broad exposure of my work but still had lots of questions. My friend advocated for the app and I ventured a toe in, slowly at first, and then more and more calculated as I became more savvy. What we all know now is that it can be a powerful tool. It became clear to me, after I noticed your gallery following my work, that I had to pay attention and learn how to leverage its use. That decision was one of a few pivotal moments that changed the direction of my work as an artist. Some attention had been building, but it was the first exhibition at Klompching in 2015 that made all the difference. It wouldn’t have happened the same way without Instagram.

AL: How and when did you first come to work with pinhole photography?

RC: I have been using an assignment to build a pinhole camera in my experimental photography courses for two decades. Over time, I began to notice a change in the dexterity of my students. What was once a simple project became a grueling task. The cameras were no longer light tight, there were no straight lines and the lids didn’t fit. Students were having difficulty with measuring, cutting and assembling the parts. It intrigued me and my observations of the change grew more careful and led me to study other aspects of their manual skills. I realized that their relationship to their physical world was much different than mine. The sensitivity I had to materials, objects, space and more, was missing or different in my students. I needed to spend time reviewing measurements, using a straight edge to draw and cut lines, holding a utility knife, and using tape while manipulating parts for bonding. Of course, there is now much written about our screen life. It is this shift to an experience of the world through digital life that has altered my students’ manual skills… dexterity. I was fascinated and set down a road to use the pinhole camera myself in a new project I would create around it.

Still Life (2017-2018), 10″x8″ unique pinhole C-Type ©Robert Calafiore/courtesy ClampArt, New York

AL: What was it that inspired you to work with this process? Was it particular photographers, images you had seen, or was it more to do with the process itself?

RC: It was a combination of things. The observations I was making around my students and a passion that was growing for a large collection of family glass I was hoarding came together to spark the start of a long-term project. I wanted to take working hands-on to an extreme. I decided to build my own cameras, use analog materials, make unique prints and employ the glass collection as my main subject. The piles of glass started with a few pieces my immigrant parents were first able to buy after they came to the United States in the 1940s and began building a new life. They are the face of a classic immigrant story. Arriving with nothing and working hard to raise a family, they taught us the value of labor. I watched my parents work blue-collar jobs for over 40 years. As I grew up, they also instilled in me a desire to learn and pushed me not only to work hard but to take advantage of schooling available to me, unlike them. The irony is that as a first generation American and the first in my family to go to college… I decided to major in art. Nobody really knew what that meant or where it would take me. I wanted this work to reflect on my family history, telling my personal story but also relaying some universal narratives found in objects. Objects that hold memories and drip with nostalgia. The camera’s unique perspective and ability to transform the real to a magical and extraordinary place made everything, my vision, possible.

AL: In many respects, you’re working with the most basic form of photographing—the pinhole camera. But it’s not necessarily the most straightforward or easy device to use. What have been the key challenges that you’ve needed to resolve?

RC: The extended exposures, the need for 15 to 20 thousand of watts of light, no viewfinder, and the color paper’s slow ASA were all challenges. When I first began working with the large cameras, 40″ x 30″, about 9-10 years ago, I was photographing male nudes placed in large-scale stage sets. The exposures were at least 20 minutes. The models had a hard time holding poses, and for me, creating images that satisfied what I had imagined was very difficult. On average we shot for three to four days on one set, at least 10, 12, sometimes for 15 takes to get a final image. I worked for about three years to create 20 or so pictures, learning new things every time and solving problems at every turn. Space, props, enough lighting, processing large RA4 materials and more were all obstacles but just as much inspiration too. Process and material are as integral to my work as are the ideas that drive my practice. The experimentation, the techniques and skill, all contributed to my ability to gain more knowledge about the work itself.

Untitled Figure (2008-2011), 40″x30″ unique pinhole C-Type ©Robert Calafiore/courtesy ClampArt, New York

AL: You took the unusual step of not only exposing directly to paper but exposing to color paper. Why not work with a negative and then print the results?

RC: From day one, when I saw the first print emerge from the chemicals, I was captivated. The negative image was able to see not only through and into the subject, but across it as well. It exposed something I couldn’t otherwise see. Something seemingly not meant for my human eyes. It came close to elevating the ordinary to that extraordinary place I wanted to reveal. It left me wanting more.

AL: Considering that photography is a visual art form that allows for infinite copies to be made, why is it important to you to make a unique art object?

RC: I think I have always thought about my photographs as objects themselves. And for me it was important to make each one as individual as the moments, dreams, and experiences that inspired them. No digital tools or technology are ever used. Given the choice of endless change and progress in technology available, I instead choose to use the simplest method for capturing an image, connecting more closely with my interest in understanding how technologies like augmented reality and artificial intelligence are changing our physical relationship to the world.

Still Life (2017-2018), 10″x8″ unique pinhole C-Type ©Robert Calafiore/courtesy ClampArt, New York

AL: The result of working with a positive photographic paper is that your photographs render in negative form. This produces some surprising and lushly wild color results. I wonder if you could say something about the extent to which you employ color theory, and if there are art historical figures or artifacts that have informed that part of your practice.

RC: The color is certainly one of the qualities about exposing the paper directly that I responded to immediately. It represented a lot for me but mainly my parents’ amazing life and the place from which they came. Of course, as I made more pictures, many other influences came into play. One of the most important would be Henri Matisse and his extensive work with objects in the studio. The repetitive use of objects over time, as well as the use of pattern and still life, has been inspiring. His relationship to the objects is fascinating and provided endless material, as it does for me.

AL: Between 2008 and 2011, you made a series of photographs on the human form. Can you tell me more about this project?

RC: This is how my work with the pinhole camera began. To be honest, I was unsure about what the series would become or what specific ideas would eventually emerge. I did sense that there was something there, and it excited me. These were luscious, indulgent, over-the-top, baroque, and decadent pictures that exposed my interest in the relationship between figure and environment. Influenced by art history, mythology, religion and my personal, sometimes intimate experiences with other people.

AL: Why did you change your subject so radically, from the human form to the still life?

RC: I was unsure where I was going with the figurative work. I needed some time to live with and think about the work I had made. The two subjects weren’t so different for me either. I am equally passionate about my relationship to both.

AL: Your choice of object for the still life studies is glassware. But it’s very specific isn’t it?

RC: Yes, as I mentioned earlier, this collection began with a few pieces from my parents and grew by taking pieces from everyone in my extended family and then friends. Most recently, the collection has been added to by way of purchase through flea markets, garage sales and antique shops.

Still Life (2017-2018), 10″x8″ unique pinhole C-Type ©Robert Calafiore/courtesy ClampArt, New York

AL: There’s also a wonderful abstraction—with both the form and temporality. How does this tie in to your creative and conceptual vision?

RC: I love the abstract passages that occur in the work. Though not abstract as a whole, finding the abstract moments in my work lends it some of the magical and otherworldly qualities that I seek to create. In transforming the ordinary to the extraordinary, abstraction within the pictures allows the subject to become more than it is. Hence the whole is greater than the sum of all its parts. Something new. Something iconic.

AL: You’ve said elsewhere that you make many more prints than what make the final edit. Is there a good amount of serendipity involved? Are you able to control the results more, the longer you are making the work?

RC: Yes, I have become much better at controlling results. However, I have always worked intuitively and find it important to my work to allow for surprises. Listening to the work and not getting stuck on what I had initially envisioned is critical. It still takes several tries with most set ups, but I am beginning to see some of those as variations and possibly something I can use in some way.

Untitled Figure (2008-2011), 40″x30″ unique pinhole C-Type ©Robert Calafiore/courtesy ClampArt, New York

AL: Are you continuing to work with still life—and glassware—or do you have other subjects you’ll be turning to?

RC: This summer I will return to working with the male figure. Given our current political climate and shift in cultural values, I feel like the work now has a more specific purpose. I will set out to embrace and promote our differences and provoke audiences to once again consider the benefits of those differences. And as has always been clear to me, in the end, we are more similar than different.

AL: People have really started to pay attention to you and your work. What have been the highlights for you, regarding this recognition?

RC: Wow! I still feel like I am dreaming. The most rewarding impact has been meeting so many fabulous artists, gallerists, writers, and industry experts. I have made countless new friends and connected with a whole new circle. The supporters and collectors are just wonderful. It has allowed me to continue to forge ahead with more work.

AL: Recently you exhibited at the ClampArt gallery in New York, where you’ve also attained representation. Anything else on the horizon?

RC: I am so very fortunate to have received exposure for my work. It is to be credited to many people like yourself, who offered support and opportunity over the last few years. I hope to work this summer and into early next year to finish a new body of work. Beyond the incredible relationship with ClampArt, I am working to get the work included in more reviews and critical essays as well as in front of curators who may find the work a good match for certain museum exhibitions and more.

Robert Calafiore lives and works in Connecticut, and is represented by the ClampArt Gallery in New York.

Tags: Art Interview, at length mag, ClampArt, Debra Klomp Ching, Klompching, Photography, pinhole, robert calafiore

Posted in Photography | No Comments »

Frank Yamrus

Monday, April 2nd, 2012

interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

Untitled (Single Man) © Frank Yamrus

At Length: You’ve been a producing artist for some 20 years, but it’s been 6 years since your last solo exhibition in New York. Why has it been so long?

Frank Yamrus: Yes, you are absolutely correct. My last one-person exhibition in New York, Bared & Bended, was a collection of 42 images—landscapes documenting my first and only winter in Provincetown on Cape Cod. These images were made in 2004 and at that time I was struggling with a personal relationship and starting to feel burnt out by my photography career. It seemed quite natural for me to seek refuge, in this place that I call my spiritual home, for contemplation.

Over the course of my winter on the Cape, I found great solace in this landscape, seemingly familiar but now blanketed by winter’s elements and surrounded by thick wintry light. After making this work, I put my camera down to reevaluate my career in photography. It was not until a couple years later that I felt the creative juices flowing, and again, it was a personal crisis—of sorts—and while in Provincetown, that inspired me to reach for my camera.

This six-year lapse reflects the time it took me to make this work and, to be quite honest, to feel comfortable with releasing this highly personal body of work to the public. Early in the process I showed some images to get feedback, but then went back to work very privately and quietly. I rarely shared any of these new images made after 2008. Last year, when Brian (Clamp) and I sat down to look at the work, he was surprised at the depth of the portfolio.

Untitled (Smoke) © Frank Yamrus

AL: It’s no secret that your newest body of work, I Feel Lucky, really results from—or at least was sparked by—a mid-life crisis. What role have the photographs performed, in the journey that you’ve made as you approached and passed the age of 50?

FY: As a photographer I don’t think I knew of another way to process this landmark event, so it was quite natural for me to reach for my camera and make these photographs. That very first impulse to take a picture felt unsurprisingly familiar and yet awkward, as I was not convinced I was ready to make work. However, once I made the first image, I was seduced, and the project began to slowly, but consistently, reveal itself. As I documented this journey, it gave me the opportunity to take another look at my life’s decisions and retrace my path to 50 as well as look beyond.

Initially, I made photographs about the “big” decisions, and some of those images feel appropriately iconic. As the project expanded, the “smaller” moments gave life to the narrative and helped me to see a more congruous life. Most of all, this process was empowering, as the images became cornerstones of my understanding, each image leading to another, creating dialogue to address the complexities of identity and life. Ultimately, I felt confidence and inspiration from these pictures and the response to this work has reinforced those emotions.

AL: Throughout the series, we witness the whole gamut of dispositions and emotions that you’ve experienced—humor, introspection, loss, joy, frustration, uncertainty, self-gratification, confidence—and yet, together, I Feel Lucky appears to be just a small glimpse of Frank Yamrus.

FR: Life is full and very complex. I agree this is but a glimpse of Frank Yamrus. Diane Arbus once said, “[a] photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know.” I subscribe to this sentiment and my imagery is, and has always been, about process and not about resolution.

The I Feel Lucky images, individually and collectively, inform. They are the evidence of life’s full spectrum of offerings: my hopes and dreams, my joy and sorrows, my happiness and pain, etc. And in spite of the filters of time and memory, the human desire to fabricate and stretch reality, these images feel authentic, and provide clarity and insight. Surely they capture the essence of my identity but, by no means, reveal all my secrets or truths.

Untitled (Boo Boo) © Frank Yamrus

AL: Does this survey of feelings, then, suggest a lack of answers, a lack of catharsis in facing up to and surviving a questioning of identity? Or would you say they represent an acceptance or acknowledgment of who and where you are?

FR: This survey of feelings is the very foundation of self-identity, and does not represent a lack of answers at all. As my personal history played out before the camera, these were the very elements that were the most closely scrutinized. I found this process to be emotionally rigorous and intellectually challenging, but in the end, oddly comforting and extremely rewarding. One of the many beautiful things about age is wisdom, and this investigation certainly uncovered the wisdom I acquired over my life’s journey. I was not looking for “answers,” although that in itself may be “the” answer. Fundamentally, I was interested in the evolution of identity. For example, two of the images I made for this series, Untitled (Lucky) and Untitled (Fountain), explore my relationship with my history and, ultimately, my identity in Provincetown.

In Untitled (Lucky) I’m disguised behind my shirt—not wanting to be recognized and not wanting to tempt fate—in this land that I once called sacred, that was my altar as I processed the loss of many friends. Sometimes I do not recognize myself in this reverent landscape under any other circumstances. Other times, when the stars are properly aligned, I embrace the entirety of that history confidently. My face is unmasked in Untitled (Fountain), as I mischievously glance at the camera and brashly spit a fountain of salt water. Fully exposed to the summery sunshine and brilliant blue water, I playfully seize the spirit of Provincetown and stake out my future in this land that holds my past.

AL: Provincetown is clearly of pivotal importance in your life. Why?

FR: When I made those landscape photographs on the Cape in 2004 that I referred to earlier, I wrote an essay about Provincetown that feels true to this day. “Provincetown is my home—it is comfort food and my favorite reading chair. It is the smell of a newborn’s hair or that moment when you first wake up in the morning snuggled against your lover. It is the place that offers me the intangibles: security and happiness, as well as the place for discovery, development, and ultimately a source of inspiration. I have spent endless summers in Provincetown but it is not where I reside. It is home, the place I visit, physically or emotionally, when I need a fix.”

Untitled (Sunset) © Frank Yamrus

AL: You published the series as a book. Do you see this as the ideal way for an audience to engage with the photographs?

FR: There a few things that I love about the book format for this project. First and foremost, the privacy and intimacy the book offers for these portraits is undeniable.

AL: One aspect of the book which works really well is that the photographs don’t appear to be arranged chronologically. It’s difficult to tell which image was made first and which last!

FR: Generally speaking, books tend to lend themselves to a linear read, which was not appropriate for this collection of photographs. With the I Feel Lucky book, I purposely avoided employing a chronological sequence. I was interested in creating an experience that reflected my non-linear process of examining, or perhaps more accurately, re-examining, these pivotal decisions and moments in my life. The dialogue created by the placement of the images was rooted in visual elements rather than related issues, feelings or chronology. This telling of my story had no beginning, middle or end.

AL: And as photographs, they’re printed at what, these days, is considered small-scale—measuring 20 x 28 inches. What determined the scale?

FR: As we all know, size matters, and for this work, this issue of scale was a delicate balance. My gut reaction was to make small prints to keep with the notion of private moments. I’m a fan of small images, and love the physical act of walking up to an image in order to digest it. However, I usually experiment with image size, and as I scaled-up the images from 5 x 7 to 10 x 14 and then finally to 20 x 28, these images came alive: facial details, gestures and background information commanded attention.

Another consideration, of course, was how the photographs would work in a gallery. My goal was to create a group conversation with the images, and as visitors walk into ClampArt they can hear the internal dialogue. At least I can. Image size and the density of the installation contributed to this success. When I took the 20 x 28 prints to the gallery, I felt this size met this goal and was happy that I was not printing on a larger scale, which oftentimes demands more visual space between the images.

Untitled (Disappear) © Frank Yamrus

AL: It’s interesting, too, that in a number of the photographs you’re not alone. Different people come into the frame and you provide little indication of their place in your world.

FR: The importance of my relationships was integral in my understanding of self. Although I don’t identify the people in my pictures, they are truly part of my life—sometimes playing themselves and at times playing others.

Untitled (Disappear) was constructed around the notion of anticipatory loss. As Sunil Gupta writes in his essay Everyman: Frank Yamrus, “Untitled (Disappear) is chilling. It evokes an insoluble mystery, a doubt that will linger forever. The nocturnal blue and the closed eyes remind us of impending gloom. This is a moment of recognition that a shared intimacy is no more. The image is more a requiem of a relationship than an image of the relationship itself.”

I don’t believe you need to know that the model in bed with me is Larry—my long-term partner of more than thirty years—to understand the significance of this photograph. In Untitled (Red), Lucas, a new love, serves as my model, but the image is more about a disconnect—anonymous sex and fetishism—than about our relationship.

In Untitled (Brooke) and Untitled (Stone), my models allowed me to explore the notion of fatherhood and visualize myself in a role that feels so completely foreign to me. The comfort I needed to make these pictures feel real was dependent on my close relationships with these models.

Lastly, in his essay The Borrowed Mirror, Bill Hunt addresses an image of me and my dad and insightfully captures my use of others in these photographs. He says: “Untitled (Dad) combines the dimensions of reality and fantasy effectively. The figure in the snapshot is less important than our sense that Yamrus’ search for meaning is entirely framed in this mirror. It is an image of reflection, handsomely and thoughtfully composed.”

Untitled (Dad) © Frank Yamrus

AL: Those who have followed your career for some time will recognize in this body of work, references to earlier photographs. Was this something that you consciously sought out?

FR: Yes, one of the underlying relationships that exist throughout this series is my relationship to photography, and my own work became fodder for this series. Being a photographer is a crucial part of my identity, and quite naturally referencing my own images became part of this process.

For example, I spent eight years in the moors of Provincetown making work about the loss of many friends to HIV/AIDS. I played off those images, that time, and my relationship to Provincetown throughout this series. Untitled (Sandman) and Untitled (Cemetery) are two examples. This tribute not only reflects my deep fondness for this place but also the importance of that time in my life and its impact on my career.

Untitled (Sandman) © Frank Yamrus

AL: Some will argue that self-portraiture is generally understood as the domain of the female artist. As a male, do you bring something different and new to this genre? If so, what is it that?

FR: I believe this argument has strength if we look at the genre in more contemporary terms; however, now we must consider the recent proliferation of self-portraits created for social media and how these pictures are shaping the complexion of this debate. Who hasn’t taken one or a hundred pictures of themselves to post on Facebook? However, my intention was to jump into this conversation with the same brutal honestly and raw vulnerability that I’ve noted in self-portraits made by women photographers. Even though my series is a blend of documentary and fiction, reality and fantasy, there is no denying its candor, humor and honesty. For me, that is what feels fresh about this work.

AL: From the point of view of commerce, do you feel there’s a place in public/private collections for these images? What transition, as an artist, have you made by placing highly personal images into the public domain—by way of the book and an exhibition?

FR: A number of these images have found their way into public and private collections, so my answer is a resounding “yes.” Although these images represent personal moments, I believe they also have a universal appeal as evidenced by these acquisitions. I generally don’t think about commerce while I am making work. But once it’s done, the work needs to find an audience. Sometimes this task is more challenging than making the work itself!

With respect to transition, I’m not quite sure enough time has transpired for me to answer this question. Initially, as I stated earlier, I was a bit skeptical about putting these images on public view, but thus far, I’ve received tremendous support. For the most part, I’m objective about the images as single pieces, however, collectively, as a body of work, I’m still attached. Interestingly, this attachment does not feel any differently than it did with other bodies of work I’ve created. Perhaps in years to come, I may feel differently about putting my face, my body, my being on public view but it’s much too early to tell. Although this work feels complete, I’m certain I will add pieces here and there. Who knows, I may go through this process as I approach 60. Right now, I’m ready to move on.

Untitled (Chapstick) © Frank Yamrus

AL: You seem to have survived 50! Do you really feel lucky and what are you moving on to?

FR: I do feel lucky, grateful and at the moment tired. The exhibition preparation and book were very consuming over these past 18 months. Next, I Feel Lucky moves to the Albert Merola Gallery for an exhibition, which will feature the images made in Provincetown, to kick off their summer season on May 18th. After that, a well-deserved vacation, perhaps some romantic walks on the beach taking corny pictures of sunsets and if my luck holds out Penelope Umbrico will find these pics on Google and incorporate them into one of her typologies! As far as new work, I’m interested in exploring my new hometown, New York, and its people.

Frank Yamrus lives and works in New York. In February 2012, I Feel Lucky was a solo exhibition at ClampArt in New York City coinciding with the publication of the accompanying book. I Feel Lucky will next be exhibited at the Albert Merola Gallery in Provincetown, May 18–June 7, 2012.

Tags: ClampArt, Frank Yamrus, I Feel Lucky, Klompching Gallery, Photography

Posted in Photography | No Comments »