at Length

Posts Tagged ‘Klompching Gallery’

Kimberly Witham

Tuesday, January 24th, 2017

interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

Pears © Kimberly Witham

At Length: How long have you been photographing and what originally inspired you to begin?

Kimberly Witham: I came to photography through a rather circuitous route. As an undergraduate, I studied Art History. Modern and contemporary art were my focus, and I often wrote about photography. The Serrano “Piss Christ” NEA scandal was happening at the time, so photography was really in the news. After some graduate study in Art History, I decided to switch my career path. I wanted to be a ‘maker’ instead of a critic. In retrospect, it makes sense that I gravitated towards photography, but at the time it was just something that interested me. I started making pictures more seriously about 15 years ago.

AL: Your practice seems to involve two key elements – the still life and dead animals. Were these two elements intertwined from the beginning or did one offer a special fascination?

KW: My still life fascination most likely comes from two sources – my mother is Dutch. I grew up surrounded by a very Dutch world-view and aesthetic. My studies in Art History furthered this fascination. I have always been interested in how images are interpreted. In particular, traditional Dutch still life paintings have intentionally coded meanings.

I have always been attracted to animals and natural history as well. Growing up, we had dogs, cats, horses, chickens, etc. I have always loved natural history museums, birds’ nests, animal bones, you name it. Ultimately, my interest in still life and my interest in natural history collided. My early work includes both still life and landscape. The animals came later, once I moved to the suburbs.

AL: The dead animals you use in your artwork originate as roadkill? Do you go out looking for them?

KW: No. The creatures in my images are found during my daily journeys to work, the grocery store, etc. I am very alert to the side of the road when I travel, but I never cruise around looking. Sadly, I do not need to go out of my way to find dead creatures by the roadside. I am always prepared to stop – I keep plastic bags of various sizes and hand sanitizer in my car. I also have a hack saw for deer antlers . . .

Raccoon © Kimberly Witham

AL: We understand that you learned taxidermy. Why did you do this and how does it affect your photographic and creative process.

KW: I learned taxidermy at the American Institute of Taxidermy in Boulder Junction, Wisconsin. I only studied small mammal and bird taxidermy, as those are the creatures I tend to find. Fish taxidermy is rather complex and holds no appeal for me! I was the only woman, and the only non-hunter in my class. Although I think I was a bit of a novelty to my classmates, they were very good-natured guys. When I did not run away screaming, I think I earned their respect.

In many ways, I consider my still life photos to be documents of sculptural constructions, which exist only for a brief time and only for my eyes. I wanted to find a way to make more permanent manifestations of my still life constructions. Taxidermy seemed like the best way to achieve this goal.

Although I am far from a scientist, taxidermy also allows a greater understanding of the muscular and skeletal systems of the animals I encounter.

AL: Which animals are hardest / easiest to manipulate and work into the images? Do you have favorites?

KW: I have a few pieces with baby deer. While they are small for deer, they are not ‘small’ – somewhere around 40 lbs or so. Due to size and weight they are the hardest to work with. Birds are the easiest, as they are so small and light. I don’t have favorites. Frankly, I would be happy if I never encountered another roadkill creature again. The creatures I work with are simultaneously incredibly beautiful and totally heartbreaking.

AL: Do you make a still life to work with the animal or vice versa?

KW: The whole process happens very organically. To some extent, I am forced to work with the pose the animal died in – rigor mortis is not forgiving. That being said, I do have sketches of ideas inspired by paintings, daydreams, etc. They often include a specific type of animal. More often than not, the photo I think I am going to make is not the one I end up with. I have a studio filled with props, tables, seed pods, skulls, dishes, fabrics, you name it. I just start moving things around to see what will happen. It generally takes a day to make one photo.

Squirrel © Kimberly Witham

AL: ’Of Ripeness and Rot’ was selected for the Fresh 2015 exhibition at the Klomching Gallery. How have these photographs developed from your earlier work?

KW: Prior to beginning work on ‘On Ripeness and Rot’ I created a series of still life images titled ‘Domestic Arrangements.’ These images include roadkill creatures and household items, but the aesthetic was much more bright, colorful and playful. I made these images in response to encountering lots of roadkill after buying a house in the suburbs. I was spending my evenings painting and remodeling an old house, and my days driving to work and picking up roadkill. I often joke that in making ‘Domestic Arrangements’ I was imagining myself as the love child of Martha Stewart and Carl Akeley (the father of modern taxidermy).

As I was finishing that project, events began to unfold in my life which made me think about mortality, beauty and fecundity. The darker aesthetic of ‘On Ripeness and Rot’ developed from that point.

AL: The reference to the Dutch Vanitas is very evident. How would you say you’ve developed this form of still life, and made it your own?

KW: Gosh, that is a tough question. Vanitas paintings referred to both the beauty of the physical world, and the looming threat of death and the afterlife. My images use this age-old visual language, but reference very contemporary conditions (roadkill is a modern problem, after all). My images are more pared down. I have always been a strong believer in the ‘less is more’ adage, and many traditional still life paintings are too over the top for me. I prefer to be more subtle, perhaps because I am dealing with such sensitive materials.

AL: Your images portray great depth of color, are obviously very well conceived, quite restrained – suggesting a detailed and determined process of making. Can you tell us something about how you make the work?

KW: Solitude is everything to me. My studio is quiet – no music, no distractions. Almost all of the images from ‘On Ripeness and Rot’ were made in my old studio, which was the enclosed sun porch on my house. I use naturally light and minimal tools—a few pieces of white foam core to bounce light, a tripod, and a camera. I work slowly and methodically. I find myself moving objects by fractions of an inch to get everything in the ‘perfect’ spot. Color and texture are important elements as well. As I said before, my studio is filled with fabric, objects, etc. and I spend a lot of time looking, thinking and rearranging. Sometimes it just doesn’t work, and I end the day with nothing. Other days it comes together immediately. When I finally have the image, there is always this brief moment where I look through the lens and just gasp for a second.

My family and I recently moved to a new house with more land, and an outbuilding studio where I can lock myself away in silence, even when everyone is home. I am still getting set up. It takes a remarkable amount of time to unpack a studio with so many props.

Hanging Birds © Kimberly Witham

AL: The symbolic use of the dead animals is consistent with the concept of the Vanitas, but you are careful to incorporate them in an understated and quiet manner. How do people respond when they realize what they’re looking at?

KW: I am conscious of the fact that I am walking a fine line. I intentionally avoid using creatures which are mutilated or grotesque. It is important to me that my images show reverence for the creatures pictured, and the natural world as a whole. Most people see that reverence in my images (admittedly, some do not). Many people initially assume that the creatures have been placed via photo-manipulation. Once they understand my working process, the most common questions are “do you where gloves?” and “what do you do with the animals once you have made the photo?”

AL: Are there aspects of the photographs that you intend to be evident, that are perhaps overlooked by viewers? For example, is there a very slight and quiet amount of humor?

KW: There is a vein of dark humor which runs through my work. It is somewhat more evident in ‘Domestic Arrangements,’ but it’s also present in ‘On Ripeness and Rot.’ There is something quite absurd about photographing roadkill, delicate tea cups and flowers in the same frame. I think this absurdity is evident in many of the images.

AL: The scale of the work is quite small, intimate, which ties in with the restrain of visual expression. Tell us about how the size relates to the image.

KW: I don’t want to emphasize theatrical and/or grotesque qualities in my work. I think the scale of the prints also references the way in which they were created. Smaller prints are more intimate, intended to be viewed by one or two people at a time. One is required to be physically closer and to slow down to really see the image. The friction between beauty and revulsion is important to me. I like the idea that a viewer will be attracted to the light and color in the work while viewing from a ‘safe’ distance, and will only notice the disturbing parts once they have come close enough to really see.

AL: Has this work been placed into any notable public collections? Where do you see it living/existing?

KW: One of my pieces was recently acquired by Lehigh University for their photography collection. Other than that, my work resides in many private collections. When I make the work, I don’t really think about where it will ultimately go. I need to make the work that is on my mind and just hope that someone will want to own it. I am always touched when the work resonates with a viewer. I see my work within the context of both art and natural history.

Fall Fruits © Kimberly Witham

AL: Which is your favorite image and do you have it hanging on a wall (which wall)?

KW: I once heard an expression about artists—that their favorite pieces are the ones they are about to make. I can’t say I have favorites exactly, but there are images which continue to resonate with me – I find myself thinking – “wow, I made that?” I am still in the process of moving into my new home, but I do have a print of “On Ripeness and Rot #10 (raccoon)” ready to hang on the dining room wall. That photograph is an ode to Jan Weenix, a Dutch painter I love. The image expresses abundance and decay in equal measure. It reflects my current mind set well. I also have work by many other artists in my home. I have some of Sarah Sudhoff’s pieces (we traded years back). I also have a portrait of Francesca Woodman, and a really beautiful sculpture by a former classmate of mine, Petra Kralickova.

AL: Are you now working on new artworks to add to the ‘Of Ripeness and Rot,’ or are you now developing the next installment of your practice with something new?

KW: Both. The past year has been very chaotic for me. My father passed away unexpectedly in April. In August, I moved to a new house and studio, complete with 5 acres of land to wander and explore. When in chaos, I tend to become even more introspective. I have been sketching some images based upon the still life tradition of the ‘laid table.’ While it may sound like a small change, I am trying to work with a horizontal composition and a greater density of objects. Additionally, I was recently re-introduced to the work of the American painter Charles Sheeler. Some of his paintings were included in the really excellent American still life exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Sheeler was both a painter and a photographer. His work is clean, spare and minimal while at the same time quite intricate and beautiful. For some reason, I find Sheeler’s work to be completely seductive at this moment—perhaps I am seeking order. I have about 5 new images, working with this spare aesthetic, with plans for several more.

Kimberly Witham‘s solo exhibition, ‘Reap’, is on view at the Filter Photo Space in Chicago, January 6 – February 17, 2017.

Tags: at length mag, contemporary photography, dutch still life, filter photo space, Fresh2015, kimberly witham, Klompching Gallery, of ripeness and rot, photographer interview, taxidermy, vanitas

Posted in Photography | No Comments »

Bill Durgin

Wednesday, November 2nd, 2016

interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

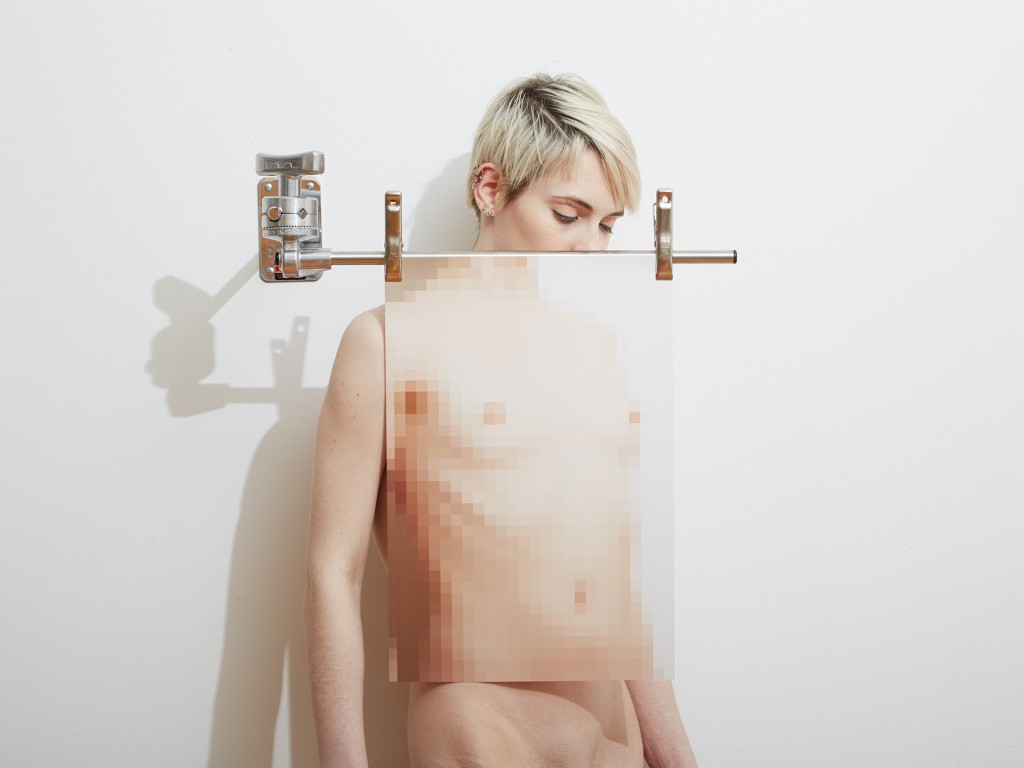

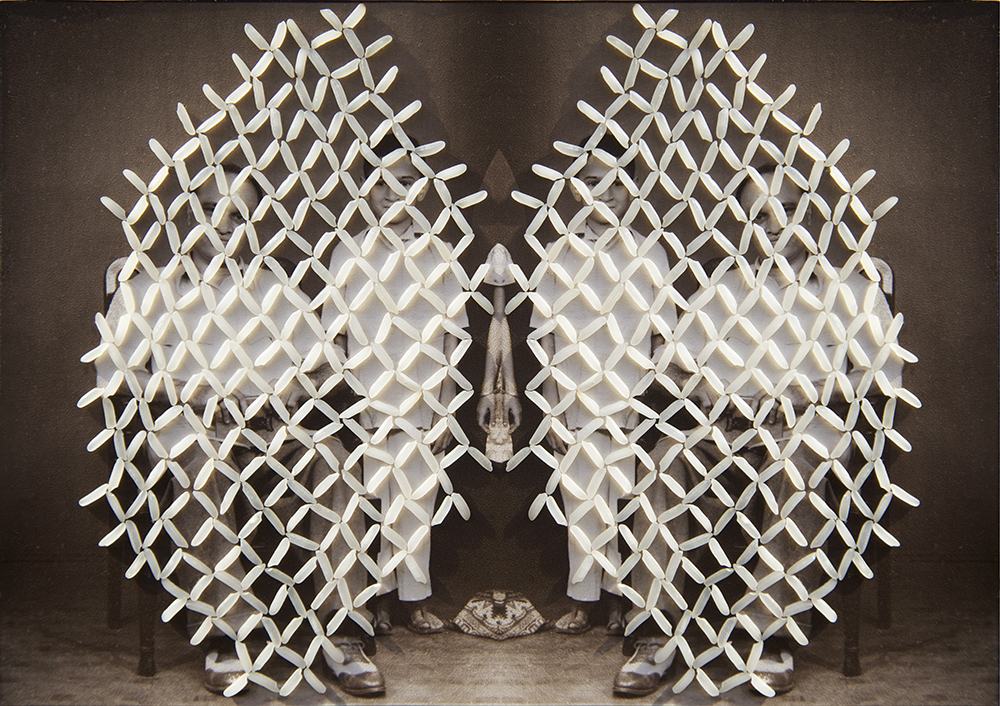

Adrian With Mosaic, 2015 © Bill Durgin

Adrian With Mosaic, 2015 © Bill Durgin

At Length: Your photographic practice, as a whole, engages with the human body. What initially inspired you to make this the focus of your practice?

Bill Durgin: I’ve always been fascinated by how the physical body how ages, the virtuosity of athletes, dancers, performers, and just how people inhabit space. For years I was reluctant to photograph the body as I wasn’t interested in the figurative photography work I’d seen. While working on an earlier series of narrative-based images, I became less fascinated with the before and after of the scene I was creating and more interested in creating something singular, something that did not have a before and after, something that existed only in one frame. It couldn’t be perceived as part of a scene that you would come across. This idea came to me of a torso draped with no arms or legs. I wanted to see if I could image that. I’d originally thought I would have to do it in postproduction, but while working with a friend who is a dancer, I realized how through contortion and perspective I could create this sculptural view in camera. I was hooked.

AL: The Fresh 2015 exhibition featured photographs from the “Studio Fantasy” series. Can you tell us more about this work—especially in terms of how it emerged from your previous series?

BD: While I was an undergrad at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, I saw a television ad for Lagerfeld Photo eau de toilet. It showed a photo session in a shabby chic loft with a stereotypically beautiful model shooting with a stereotypically handsome photographer, no other production staff. Shot in black and white, very diffused, the shoot was a flirtatious dream sequence. At the time I was working in commercial photo studios and the school’s darkrooms, sweating, getting dirty, smelling of chemicals, schlepping equipment, enduring the demands of anxiety-inducing production schedules…. I loved the irony of it, seeing the photographic shoot portrayed as fantasy while working in its much less glamorous reality.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pbS2ha5IQLY

I was reminded of this while shooting head shots for a friend. He brought a bottle of wine and offered me some. While I do love wine I can’t drink while I shoot and said so; there are too many variables to focus on, and I’ll inevitably mess something up. He was surprised and said he had a completely different picture of what I did on a daily basis. When I realized that even my friends had this fictionalized glamorous view of my studio practice the idea for Studio Fantasy came immediately. Unlike other series the name came first, and I started showing the edges of the sets and some of the banality around studio practice. In my previous bodies of work I carefully composed each image to avoid stray objects and supports. This series put those in the forefront. I wanted to depart from the set of rules I had laid upon myself, freeing up my technique and exploring some new ideas while still investigating new ways of imaging the body.

Fake Wine Spill, 2015 © Bill Durgin

Fake Wine Spill, 2015 © Bill Durgin

AL: In this body of work, you have maintained the human form as a central focus, but also incorporated photographs of objects without bodies. Why is this?

BD: Still lifes in the series are about making the banal beautiful, elevating studio tools and props to be the primary subject. Using gaffer tape to make a graphic tonal composition, the beauty of a plastic bag suspended from a C-stand, apple boxes leaning against each other with a print that visually erases one, a fake wine spill shot to reveal its inherent farce.

AL: In many respects, then, the studio, along with its various props, has emerged as a key subject. Can you tell us more about how you’ve explored this?

BD: “If I was an artist and I was in the studio, then whatever I was doing in the studio must be art.” – Bruce Nauman

The studio, specifically my studio, is the key subject in this series. Aside from the obvious titular reason, I’ve been interested in the labor of studio practice. I have always revered Bruce Naumans’s approach to working in the studio, going there everyday working through the boredom of being alone all day and making that the work. Also his approach to creative blockage, “It generally goes back to the idea that when you don’t know what to do then whatever it is you’re doing at the time becomes the work.” – Bruce Nauman

I use the studio as a blank slate from which to build an image. There were certain rules I set as my work working method: show edges of the set or parts of the studio, use minimal props, a single bare bulb light source, include any tool used including color charts. I start with an empty studio area and bring in whatever support catches my eye that day. When working with a model, I’ll direct them to where the focal point is and then we’ll improvise and refine a pose. I’ll then take part of that image, pixelate it, print it, then bring that back into the set and continue improvising and refining.

Priscilla With Color Checker, 2015 © Bill Durgin

Priscilla With Color Checker, 2015 © Bill Durgin

AL: It’s not just the studio that you examine, but this notion of the photographic space as well. What visual devices have you employed to examine these ideas?

BD: The camera itself is an editing tool; you are creating a visual space and omitting anything outside of the edge of the frame. The lens has a singular monocular view, which I exploit to achieve my composition, showing and hiding parts of the studio, the set, and sometimes the figure. “Studio Fantasy” is about making a photograph, not a documentary of what happens during the shoot.

I was looking at a lot of sculpture throughout this series. While I do see much work in person, I would always be looking at photographs of it in my studio. I was taking inspiration not just from the sculptures themselves but how they were translated into the photographic space. I treated my sets as a sculpture and documented them from a very specific perspective.

AL: The use of the pixilation appears to be a nod toward contemporary image consumption, through platforms such as social media, for example, but we wonder if there is something else going on. Can you expand on this element of the work?

BD: I saw an image on Instagram where someone had pixilated part of a body to fit the Community Guidelines. I was drawn to how the image looked more like a beautiful collage than a censored image. I could never find the image again, and perhaps it’s just the memory of that image that inspired this direction. I was drawn to the idea of using a form of censorship as a tool for incorporating a different dimensional plane within an image, like a collage. It also became a new way of abstracting the body and calling attention to the aspect of nudity rather than hiding it. The viewer becomes very aware of what is seen and what isn’t.

AL: How do you want your work to be received or understood in this context?

BD: I want the pixilation to be seen as a form of collage. I first saw it used in television news as a way to keep persons and incriminating documents anonymous. It was also sometimes used to hide nudity, often streakers at sporting events. Now I see it most often used on social media for the purpose of obscuring nudity, especially on Instagram. While I use it as a compositional tool, I also enjoy that it references anonymity and censorship.

Jen With Mosaic, 2015 © Bill Durgin

Jen With Mosaic, 2015 © Bill Durgin

AL: Overall, your practice presents itself as disciplined, formal, rigorous. How do you go about making what you do? What is your process?

BD: I usually start with a bare studio and an idea. That idea could be a sculpture I saw, a pose in a painting, a new piece of equipment in the studio, or just a piece of plywood leaning against the wall, and more often than not it is a combination of props and a pose. This idea is a launching point, something to set up before the shoot begins. When I get on set with the subject, a model, prop or myself, improvisation takes over. I select an area to be pixilated, print it out and bring it back into the set when improvisation takes over again. I’ll often have to do several prints, try different supports, a constant back and forth between staging the new set and improvising with it.

AL: Do you view your practice as a formal interrogation of the subject? If so, what are the key qualities or concerns that thread the different bodies of work together?

BD: My work is more of a personal interrogation of the subject(s). While there are definitely formal issues investigated, representation, figuration, compositional strategies, theories of perception, there’s also very personal motives and emotional content within the images. I’d say that the main elements that go through all my bodies of work are image construction and a constant push for the new ways to image the body through various formal and personal perspectives.

AL: Would it be fair to say that the “Studio Fantasy” series interweaves several theoretical/conceptual notions? For example, the photograph as constructed and mediated, the labor of the hand, scopic illusion and so on?

BD: Definitely. Since the beginning I’ve always focused on constructing photographs; it’s just what I’ve been drawn to do, and with each body of work a new set of concerns gets added: historical context, both photographic and art historical; the use of camera angle and perspective, and the gaze created by that perspective; studio labor; body image; photographic space as partial truth. Some images address more concepts than others, and “Studio Fantasy” brings in ideas of creating images in a digital age while the construction of those images finds its core in hands-on studio technique.

AL: The color palette of the series is very restricted, why is this?

BD: I wanted the studio to be the ground from which these images emerged, so that determined the palette. Being a minimalist, adding color wasn’t a concern. I guess my studio just isn’t very colorful.

Self Portrait, Gray Card and Multiclip, 2015 © Bill Durgin

AL: It’s also somewhat quieter than your previous work, less risqué. Do you think this helps to make photographs more accessible and palatable to art collectors? Or, if this not a concern or conscious shift?

BD: I actually thought this work was more risqué, bringing the topic of nudity right to the front. Perhaps the bodies are more recognizable, but there was no conscious effort to make anything more palatable. I wasn’t thinking of sales while making it, just ideas and experimentation.

AL: Following the Fresh 2015 exhibition, you were shortlisted for the Aperture Portfolio Prize. What impact has this exposure had on your success as an artist, and what is next on the horizon?

BD: It was an honor to be in Fresh 2015 and shortlisted for the Aperture Portfolio Prize. I definitely had a bump in exposure, but most of all it is validating as an artist to be recognized for your work. This was a new direction for me, so it has encouraged me to continue expanding, growing and experimenting with my work. Right now I’m working on a series entitled “Figure-Ground,” stemming from the principal in gestalt theory that a figure is perceived through its distinction from its background. I am layering several images from a single shoot, partially erasing and layering figures, blurring the boundary between what is figure and what is background.

Tags: Bill Durgin, Fresh2015, Interview, Klompching Gallery, Photography, Studio Fantasy

Posted in Photography | No Comments »

Peter Croteau

Wednesday, July 1st, 2015

interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

Mountain I, 2012 © Peter Croteau

Mountain I, 2012 © Peter Croteau

At Length: How did you start the “Mountains” project, and what was the inspiration?

Peter Croteau: The project began while I was in graduate school at RISD. In my work I explore the in-between spaces in the landscape, otherwise known as spaces of dross. During this time I was attempting to shift my process and see the everywhere-nowhere spaces I had been photographing in a new way. The shift occurred when I was photographing piles of snow at night. I was interested in the liminal quality of snow, and the strange contrast snow has with the night sky under parking lot lights.

One of the photographs I came back with was different from the others. I had moved in on the space, and the camera frame had been transformed into something ambiguous—something that could be from another world. This ambiguity was an exciting new way of representing the landscape for me, and I decided to return to many sites of dross that I had been photographing, to attempt to transform them into something other.

One of my main inspirations for the project was Joe Dealʼs last body of work, West and West. Deal became tired of the amount of photography that replicated New Topographics aesthetics and only focused on manʼs impact on the earth. He felt that photographs of suburbia, and man-inflicted landscape, are in danger of becoming too familiar and easily dismissed.

With the oversaturation of images of ravaged landscapes comes a sense of complacency in the amount that we consume from the land. In West and West, Deal decides to turn the other way and re-imagine the Great Plains as how they may have been before we were there, as he imagined them as a child.

I found this act of reimagining the world key to my process as I began reframing spaces of dross. I found the process of turning a mound into a mountain was an act of reimagining the landscape as a wild space.

Mountain II, 2012 © Peter Croteau

Mountain II, 2012 © Peter Croteau

AL: One of the first impressions of the photographs is one of monumental grandeur, juxtaposed with ambiguity regarding scale. What statement are you making with such a bold and confident portrayal of seemingly banal mounds of dirt and rubble?

PC: From my photographs I’d like people to take away the idea that nature isn’t just a physical thing, but also a state of mind that we can expand to include more elements than just grand and distant spaces. Nature can include what is right outside our back door. We need to look at our own surroundings—whether urban or rural—as natural ecosystems. We need to factor how man, space and other life forms fit together rather than see ourselves as estranged from the natural world.

I attempt to accomplish this by turning mounds into seemingly wild spaces shaped by the hand of God, only to have the viewer realize that it is in fact the human hand that does the shaping. Humans create these ready-mades for me to transform. This transformation asks viewers to question what constitutes sublime, wild space. Through my reframing of these transitional spaces I want to show how humans shape, build, destroy, and regulate the landscape through capitalistic systems.

If this free will were to be fully realized and society could moved beyond a desire to simply accumulate wealth, then we could begin to understand just how we need to shape this world. This may open possibilities for new designs and life styles, allowing us to coexist with the world in a state of balance.

AL: Does the ambiguity of scale also extend to the actual geographic locations of the photographs? In other words, could they be anywhere or somewhere specific?

PC: The ambiguity of the objects I photograph extends beyond actual geographic locations. The viewer is not supposed to know where the photograph was taken, but is allowed into a space where they can make their own assumptions about where in the world they are. The sites I photograph are so commonplace that they are everywhere and nowhere.

Mountain III, 2012 © Peter Croteau

Mountain III, 2012 © Peter Croteau

AL: How was it that you selected the locations? Are they places that have some personal or other significance?

PC: Most often the sites I photograph are something I see when driving, and then return to at a specific time of day. The only personal significance they hold for me is that I am drawn to site of the in-between. Having moved over a dozen times in my life, there has always been a sense of dislocation in my life. I feel an affinity to the everywhere/nowhere quality of these spaces. Beyond personal affinity, I am interested in how problematic—but necessary—spaces of dross are, and how they speak to our economic relationship with the land of mass consumption and sprawl.

AL: In some respect, the landscapes you’ve depicted seem innocent and natural; it’s only with closer scrutiny that visual hints indicate human intervention. Is there a fine line that separates the two?

PC: Humans have made this fine line exist. I am trying to break that line between what we see as natural and what we see as manmade.

Mountain IV, 2012 © Peter Croteau

Mountain IV, 2012 © Peter Croteau

AL: What do you want the viewer of your photographs to see?

PC: I just want my viewers to be caught in a moment of ambiguity, where they are forced to question: What is reality? What is nature? And how do I relate to them? I want them to question the existence of the mountains and likewise ask their existential questions of themselves.

AL: The photographs display a formal composition. Why have you photographed them in this way?

PC: I have studied a history of landscape representation and employ many formal tropes from photographers and painters. More specifically, I am using the tropes of the Hudson River School painters, who depicted the American landscape as a vast beautiful land that was ripe for the taking under the philosophy of manifest destiny. By framing dross in relation to these historic painters, I am drawing up a dichotomy between the expansive landscape of dross that exists now and the wild frontier of the American West.

AL: Despite their formality, or perhaps because of it, the mood is very stoic and melancholic.

PC: In my attempt to make the unexceptional spaces in the landscape look like somewhere fascinating, the mood is very important. Getting my camera down as low as I can, and looking up at these objects in the landscape, creates a sense of monumentality and stoicism in the objects. Through my use of lighting and other weather factors, I attempt to draw mood out of the stoic forms. This mood can range from a deep melancholy to one of excited beauty. Use of lighting and weather to bring out the mood of the objects is one of the most important aspects for making these photographs believable—as distant, sublime spaces.

Mountain XI, 2012 © Peter Croteau

Mountain XI, 2012 © Peter Croteau

AL: The photographs are very fresh, in the sense that you have depicted something rather unexpected and often overlooked. What was it that fascinated you about common piles of earth, or did you seek them out in order to visually communicate an already-formulated concept?

PC: What fascinates me is the existential nature of man I see held within these spaces. I see man creating his own destiny in the ever-shifting American frontier of dross. I am trying to further the ideas set forth by Joe Deal, about reimagining the world as something other. By focusing in on sites where man has had the most direct involvement, but reframing them as something natural, I am creating my own vision of the world, which speaks to how we bend the planet to our own will.

Mountain XVI, 2012 © Peter Croteau

Mountain XVI, 2012 © Peter Croteau

AL: Are you continuing to make landscape photographs?

PC: I am working on a couple of different projects right now. First off, I have been trying to further develop the dialogue I started with “Mountains,” by trying to make spaces of dross look like other elements of the natural landscape, such as valleys, rivers and glaciers.

I am also just photographing the in-between spaces around Providence, documenting the shifting landscapes and trying to replicate some views after a period of time has passed.

Also, I have been going through photographs I made during undergrad in Stroudsburg, PA, of the main street and how it leads into a continuous strip that I feel comprises much of the American landscape.

Lastly, I have been skateboarding for over 15 years, and I am working on a project photographing the marks skateboarders leave behind on walls and other surfaces. I feel these marks relate to those of the Abstract Expressionist painters. I am attempting to make the case that these marks from skateboarding are analogous to the marks made by the modern artist.

Peter Croteau is an American artist and graduate of RISD. He was selected as one of the exhibiting artists for Klompching Gallery’s 2013 edition of FRESH: The Wall/The Page/The Internet, July 17–August 10, 2013.

Tags: Fresh 2013, Klompching Gallery, Landscape, Mountains, Peter Croteau, Photography

Posted in Photography | No Comments »

Maxine Helfman

Tuesday, November 19th, 2013

interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

White Satin Bow, 2012 © Maxine Helfman

At Length: The series of boys in girls’ dresses is called Fabrication. Tell us about the relationship between that title and the subjects.

Maxine Helfman: I’ve always been fascinated by the ‘elephant in the room,’ so I titled each piece by a description of the fabric of the dress, shifting the focus to the ‘fabrication,’ rather than the gender. It was also interesting that the word fabrication has another meaning—a falsehood.

AL: The boys in the portraits display all the usual emotions one would expect of a boy when dressed in a dress!

MH: I cast all of the boys to be ‘typical boys.’ The sessions were very matter-of-fact, but almost every one of the boys came out with the clothing on backward. Buttons and zippers in the back made no sense to them.

AL: The dresses you’ve used look quite retro. Were they selected specifically to reflect a specific era/time?

MH: I wanted the dresses to be more timeless, as those selected seemed to be.

AL: Why is that?

MH: It gives them more of an innocence and less reference to a specific time, keeping the time-frame more vague.

Blue Organza, 2012 © Maxine Helfman

Blue Organza, 2012 © Maxine Helfman

AL: The color palette and incorporation of a ‘falling away’ of the background at the edges of your photographs also adds some value to this retro feel. Is there a particular aesthetic that you are referencing in this context?

MH: The edges and color palette appear in a lot of my work; it takes the photographs out of time and place. For the same reason, I also tend to shoot a lot of my work without props and on simple backgrounds, so those details don’t overshadow the message.

AL: It’s interesting that a certain level of ‘age of innocence’ comes across through the portraits. Were you looking to create this emotional response?

MH: While I take a simplistic approach to most of my work, the issues they bring up are much more complicated. During the process of producing the work—and showing it—I am always surprised at the observations and discussions they bring up.

AL: Also, does this in some way reflect a sense of loss, that only those born pre-1970′s might relate to?

MH: I can only speak for myself, but I think you might be right. We live in a world of too much information and no regard for privacy. I certainly grew up in a much simpler time.

Size 7 Floral, 2012 © Maxine Helfman

Size 7 Floral, 2012 © Maxine Helfman

AL: The personalities on the faces of the boys, and in their body language, are quite absorbing. More than one visitor seeing your work at the Klompching Gallery didn’t realize that the subjects were boys at all. How challenging was it to capture the appropriate expressions that you were looking for with each subject?

MH: I was looking for an age that I knew they could make their own decision about whether to do the project. I wanted to make sure they were all comfortable with it. They were all very natural.

AL: Elsewhere, you’ve stated that you like to raise questions through your photographs, rather than answer them.

MH: I usually approach issues of race, gender, culture and identity. With the boys, it is simply a boy in a dress, yet some are bothered or disturbed by it.

AL: What are the questions that you want people to ask?

MH: What does it represent? What is it that makes it unsettling? Would girls in boys’ clothes raise the same issues? My photographs are about questioning and challenging beliefs.

AL: Why is this important to your fine art practice?

MH: I’m not someone who wanders with a camera. The subject is usually an issue I’ve been thinking about, or an idea that comes from something I’ve heard—I listen to a lot of NPR and BBC. I think there are a lot of ways to get a message out. Sometimes that message is through photojournalism or documentary, or in my case it’s fine art. It’s important for me to use it as a voice.

Pink Iridescent, 2012 © Maxine Helfman

Pink Iridescent, 2012 © Maxine Helfman

AL: And yet, identity, or the construction of identity, is a theme that runs through your other work. How do you see your different projects relating to each other?

MH: I take the same straightforward approach to challenge and confront the issues of identity. My series Historical Correction is a collection of what look like traditional Flemish portraits, but the subjects are African American.

AL: What are you working on now and what’s coming up?

MH: I’m finishing up a series of African American geishas and have a few other series in the works.

Maxine Helfman is an American artist who was selected as one of the exhibiting artists for Klompching Gallery’s 2013 edition of FRESH: The Wall/The Page/The Internet, July 17–August 10, 2013.

Tags: Fresh 2013, Klompching Gallery, Maxine Helfman

Posted in Photography | No Comments »

Manuel Cosentino

Thursday, August 15th, 2013

interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

Behind a Little House (A), 2008 © Manuel Cosentino

Behind a Little House (A), 2008 © Manuel Cosentino

At Length: The Behind a Little House series was photographed over a two year period from 2008–2009. What were your considerations when making the initial photographs—what were you looking for?

Manuel Cosentino: I find it essential to work on long-term projects, because it allows me to develop a strong relationship with the subject and become familiar with all its idiosyncrasies. I select locations which seem to want to share a universal story and start collaborating with them. It is a two-way dialogue which entails a lot of listening on my part. Each photograph needed to play a specific role in the project—individually and as a whole—and I devoted a great amount of time, while on location, to thinking about this relationship and how it would have impacted the reading of the work. Each day was unique and had something to say, but only the sky in the first photograph could have started the series, and only the one in the last could have ended it.

Behind a Little House installed at the Klompching Gallery, 2013. © Klompching Gallery

Behind a Little House installed at the Klompching Gallery, 2013. © Klompching Gallery

AL: The resulting series had not been made public until 2012, suggesting a period of refinement and editing. Talk us through how you arrived at your sequence of eight photographs, and why you have grouped them as a set of five, a pair and a single image?

MC: I always like to forget about the photographs for a while, so that I can see them for the first time once more—it clears my mind. I devoted a long time to the construction of the project as a whole, focusing on the dialogue between all the images. I considered carefully the number of pieces and wanted to create an installation which could have been easily exhibited around the world without taking up too much space. There in no secondary photograph; they’re all key. The three-set structure in some ways follows in the footsteps of the three-act-play, devised as far back as the Roman theater. They set the rhythm of the work and punctuate the overall dramatic structure of the project. The viewer is taken through a visual journey. It starts, in a literal sense, to becoming allegorical and symbolic, and finally the last piece reveals the conceptual side of the artwork.

AL: One of the questions that many people have asked is, “where is the little house?” You choose not to say exactly where it is. Why is this?

MC: I never mention where the little house is. I prefer it to transcend geographical placement and become an idea. We all live under the same sky after all …

Behind a Little House (B), 2009 © Manuel Cosentino

Behind a Little House (B), 2009 © Manuel Cosentino

AL: So, the title itself tells us that the work is not so much about the house, but rather about the sky behind. Is the sky a metaphor for a bigger concept?

MC: Throughout the work there is a stratification of layers that anyone can choose to explore or not—it’s up to the public to decide how deep they want their involvement with the project to be. The title plays a fundamental role, as do the little house and the sky—they all work together. The last photograph in the series, and the participatory artist book, take the symbolic and metaphoric meaning of the work even further, allowing for all facets of the project to be fully experienced.

AL: In many ways, then, the photographs appear quite simple, and yet they speak in so many different ways to different people. Is there an overriding message in the work, or a sense of universality that you are seeking to portray?

MC: Simplicity is the best language to talk about anything complex. Anyone can relate to the little house. I chose it because it reminded me of the little house that I’d draw as a child. It holds a strong symbolic value and speaks the same universal language as the sky. When looking at the photographs, anyone pours into them his or her own life and sees them in a unique way.

Behind a Little House (D), 2009 © Manuel Cosentino

Behind a Little House (D), 2009 © Manuel Cosentino

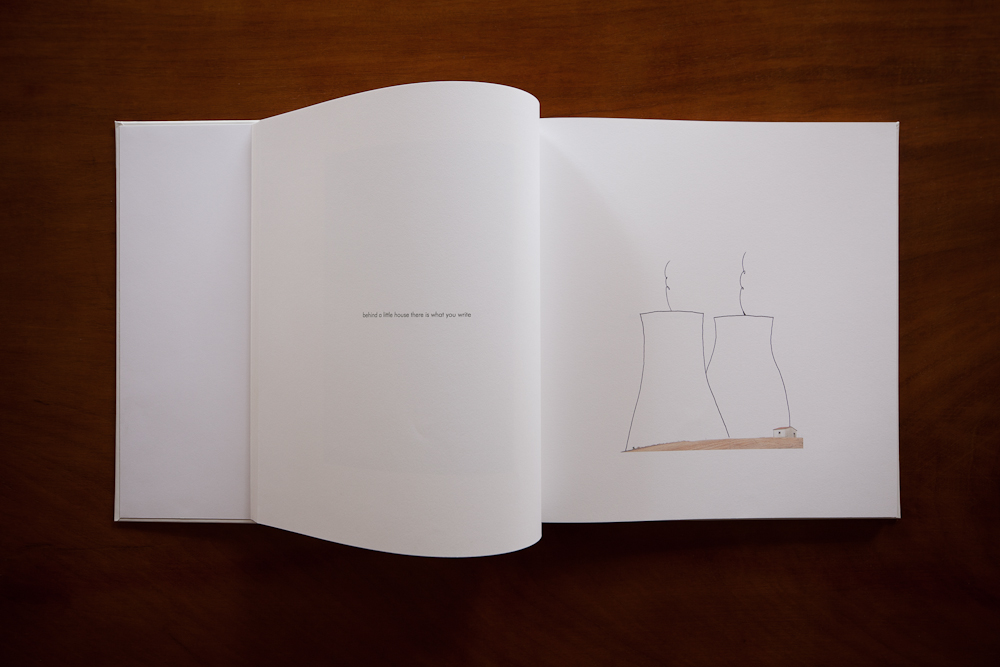

AL: An interesting element of the work is the addition of an artist book that visitors to the exhibited artworks are invited to draw in. Can you explain what this is and what it means to you?

MC: I am interested in exploring alternative ways to present, interact with, and consume photography, as a way to activate and facilitate the dialogue between the artwork and the viewer. The participatory artist book allows me to develop a deeper bond with the public, and lead them from a position of observers to that of active participants. I always imagined it a little bit like a self-contained universe. The first photograph starts the series with a ‘Big-Bang’ and sets everything into motion; the last is a new beginning—it represents that piece of ‘carte blanche’ that we are all given with our lives. By drawing in the book, anyone is at the same time breathing life into it, keeping it alive page after page, and is also responsible for his or her contribution within a wider context.

AL: Besides inviting the public to become part of the project, you contributed yourself to the artist book with the first drawing, featuring two power plants towering behind the little house. Why have you chosen this subject?

MC: People coming to the exhibitions are first drawn to the wall-mounted photographs and are meant to happen upon the participatory artist book afterwards. It is at this time that, suddenly, the power plant drawing starts to suggest a further layer of interpretation. It was inspired by one of Mitch Epstein’s most famous photographs from the American Power series. When looking at ‘my little house’ embraced by pristine skies, and ‘Mitch Epstein’s little house’ dwarfed by power plants—they might look like two very different and distant places. But I strongly believe that they’re not that far apart ….

Behind a Little House, artist book. © Manuel Cosentino

Behind a Little House, artist book. © Manuel Cosentino

AL: Each exhibition of the artwork has a new book. What happens with the books at the end of each exhibition?

MC: To respect the participant’s trust, the artist book is not for sale and at the end of each exhibition it becomes part of my personal collection, or is donated to a public/private institution. Furthermore, anyone who has taken part in the project is credited at the end of all future books. That is also where my name first appears in the artist book, as I don’t see myself as its author, but as one of the many people who breathed life into it. In the future I envision an exhibition where all participatory artist books will be brought together and exhibited as a whole.

Behind a Little House (H), 2009 © Manuel Cosentino

Behind a Little House (H), 2009 © Manuel Cosentino

AL: This is your first body of work as an artist, and it has been embraced by so many people—going viral on social media/blogs/online magazines, exhibited across a number of venues in Europe, Asia and the USA—and has been acquired for collections, including the Bibliotéque Nationale in Paris. Are you now working on something new?

MC: I think that it is very ironic, for my first body of work to go viral. I often refer to it as an intimate participatory art project, specifically because I have chosen to sacrifice the dissemination opportunity given by large-scale web 2.0 distribution/interaction methods. I’ve chosen instead, to communicate through the intimacy of a book—in order to reclaim a physical connection with the public. The media attention has been truly exciting and has allowed me to reach an audience far beyond my wildest dreams. However, I do believe that the photographs and the participatory artist book should be experienced in the flesh. As for the future, I have been working relentlessly on my next project, which will be released in 2014, following a four-year obsession started—similarly to the Behind a Little House project—from a simple spark.

Manuel Cosentino is an Italian artist who was selected as one of the exhibiting artists for Klompching Gallery’s 2013 edition of FRESH: The Wall/The Page/The Internet, July 17–August 10, 2013.

Tags: Fresh 2013, Klompching Gallery, Manuel Cosentino

Posted in Photography | No Comments »

Priya Kambli

Tuesday, August 13th, 2013

interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

At Length: In your statement about the Kitchen Gods series, you said that a key kernel for the work was discovering a family photograph that had been damaged. Tell us more about that.

Priya Kambli: One of my most startling early childhood memories is of finding one of my father’s painstakingly composed family photographs, pierced by my mother. She cut holes in them, so as to completely obliterate her own face while not harming the image of my sister and myself beside her. Even as a child I was aware that this act was quite significant, but what it signified was beyond my ability to decipher. As an adult I continue to be disturbed by these artifacts, which not only encompass the photographer’s hand but also the subject’s fingerprints.

Even though her incisions have a violent quality to them, as an image-maker I am aesthetically drawn by the physical mark—its presence and its careful placement. These marred artifacts have formed a reference point and inspiration for my new body of work, Kitchen Gods, but they do not limit the form my own work takes.

The purpose and focus of this series is to create and contextualize a body of work that creatively references the conflict in the image-making process—my father constructing an image of his family through his camera lens and my mother re-shaping that image with her knife.

Muma, Sona and Me—from the family archive of Priya Kambli

Muma, Sona and Me—from the family archive of Priya Kambli

AL: You’ve gone on to create your own narratives, utilizing various techniques of manipulation. What relationship do these techniques have to the content of the photographs? For example: your use of rice and flower petals.

PK: My son, Kavi, once asked me if we were going to keep the flowers that I was buying at the grocery store, or if they were for art. The series, Kitchen Gods, is a conversation with my ancestors. The conversation begins with the family photographs that I carried with me in my suitcase when I moved from India to the United States, and which have been my companions ever since.

My choice of materials is dictated in part by play, and figuring out what works in the studio. My preference tends to be for materials that are domestic and humble in nature, and usually grounded in everyday use. But I think, besides being humble, simple, or common items, rice and petals (for example) are used to adorn household shrines—the kind of shrines Indian housewives keep in their kitchens. You might drape a garland of flowers over a holy man’s portrait, or a dish of rice might be kept, ready to use in small ceremonies (arthi). In my work I re-contextualize the familial qualities of these things, to serve my own artistic and creative purposes.

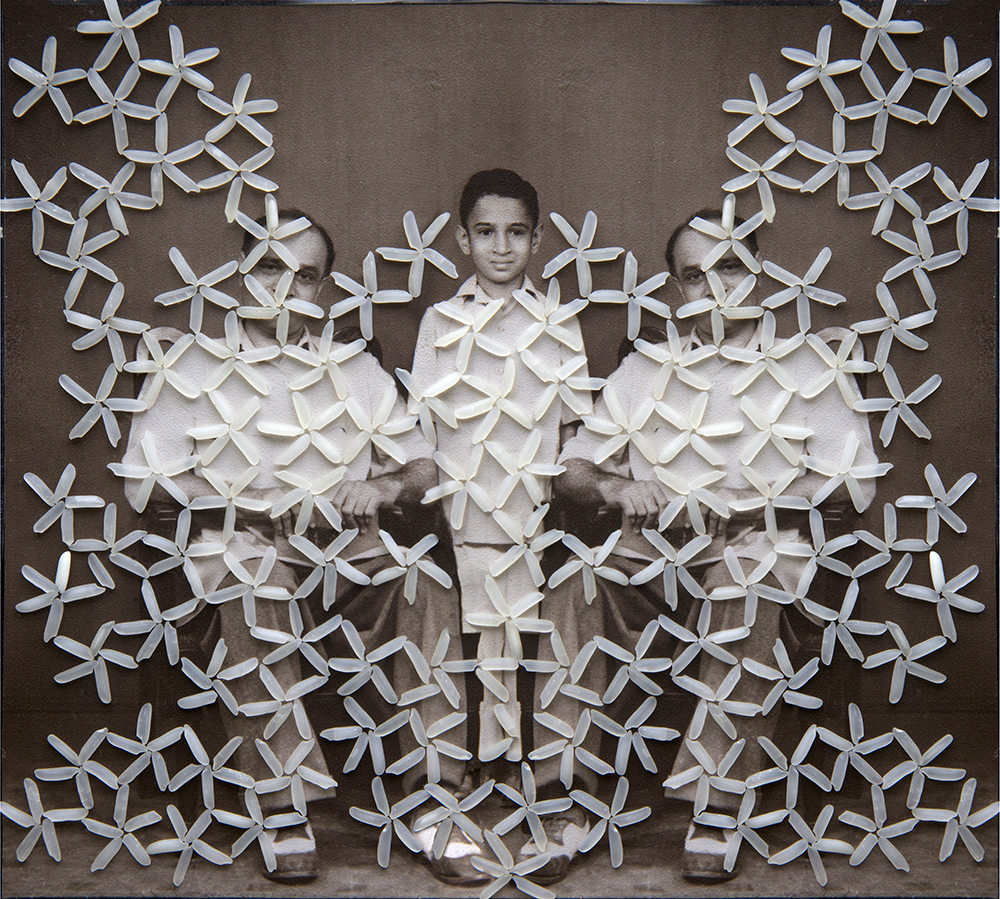

Mama and Dada Aajooba, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

Mama and Dada Aajooba, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

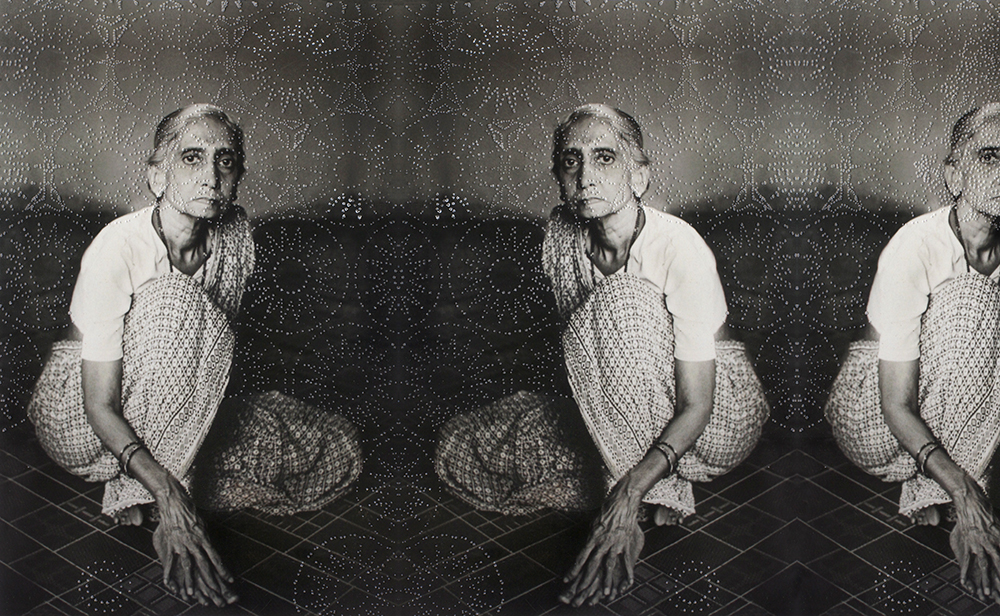

AL: And the intriguing technique of creating a partial mirror-image?

PK: Going through the family photographs I realized, because of the way my father photographed, there were a lot of duplicates–well, almost duplicates; the images had slight variations. I was really intrigued by this element of repetition and wanted to incorporate it into my own work.

Dada Aajooba and Dadi Aaji, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

Dada Aajooba and Dadi Aaji, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

AL: There is the overarching theme of memory and family. What is your personal story regarding the meaning of these photographs? What does the title Kitchen Gods mean and how does this relate to the people in the images?

PK: My need to decipher and address my family photographs is personal. My work is rooted in my fascination with my parents, both of whom died when I was young. Therefore, for me these family photographs hold even more mythological weight. In my work I labor to maintain my parents and my ancestors, the way Indian housewives do their kitchen deities. I also strive to connect the generations—my ancestors and my children—who have been separated by death and migration. Like my mother, I alter these photographs to modify the stories they tell.

Aaji, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

Aaji, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

AL: The photographs are very intimate, and this is further grounded by their scale. Have you executed them in this way with the audience in mind or something else? And then, each photograph is presented with an expanse of white space surrounding the images. What is the purpose of this visual device?

PK: The scale of the image is derived from the original unaltered photographs themselves. Most of them are pocket sized, intimate, and now have my finger-prints pressed into them. I am gentle and rough when handling them, knowing full well that they are irreplaceable, but at the same time unable to refrain from playing with them—like paper dolls, cajoling them to come alive. The purpose of anchoring the images in the white space is an aesthetic as well as pragmatic selection, dictated by my choice of scale. I wanted to give the image prominence, without having to compromise on the choice of scale.

AL: Your photographs are clearly highly personal statements about family and the role of family photographs. In a wider context, what is the value of the family album to you? From the point of view of parent, artist and also academically—the family album as genre?

PK: I am fascinated by family albums, but I am also realistic and pragmatic about them. I am aware that for my children, disconnected from my roots, photographs of my family and ancestors don’t have the same pull that they do to me—their [my children’s] interest in these photographs and people is that of kind strangers. Through this work I am attempting to recreate a much more tangible family album that I can bequeath to them.

Dada Aajooba and Mama, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

Dada Aajooba and Mama, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

AL: What has inspired you to be a photographer?

PK: I never wanted to be a photographer. My most vivid childhood memories are of standing beside my sister in front of my father’s Minolta camera—waiting, while he carefully framed and exposed us onto film. My father, an amateur photographer, took the task of making images rather seriously. And we (my father’s family) often found ourselves to be his unwilling subjects. Our reluctance was related to his perfectionism. We, his subjects, were constantly herded from one spot to another, posed in one pool of light and then another. As a child I was certain that being photographed by my father was my punishment.

Interestingly I find myself donning the role of the photographer, demanding that same commitment that I balked at, hence most of my subject matter tends to be objects, artifacts or self-portraits—things that I can put through a wringer without feeling that I am donning my fathers shoes.

Priya Kambli was selected as one of the exhibiting artists for Klompching Gallery’s 2013 edition of FRESH: The Wall/The Page/The Internet, July 17–August 10, 2013.

Tags: Fresh 2013, Klompching Gallery, Priya Kambli

Posted in Photography | No Comments »

Frank Yamrus

Monday, April 2nd, 2012

interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

Untitled (Single Man) © Frank Yamrus

At Length: You’ve been a producing artist for some 20 years, but it’s been 6 years since your last solo exhibition in New York. Why has it been so long?

Frank Yamrus: Yes, you are absolutely correct. My last one-person exhibition in New York, Bared & Bended, was a collection of 42 images—landscapes documenting my first and only winter in Provincetown on Cape Cod. These images were made in 2004 and at that time I was struggling with a personal relationship and starting to feel burnt out by my photography career. It seemed quite natural for me to seek refuge, in this place that I call my spiritual home, for contemplation.

Over the course of my winter on the Cape, I found great solace in this landscape, seemingly familiar but now blanketed by winter’s elements and surrounded by thick wintry light. After making this work, I put my camera down to reevaluate my career in photography. It was not until a couple years later that I felt the creative juices flowing, and again, it was a personal crisis—of sorts—and while in Provincetown, that inspired me to reach for my camera.

This six-year lapse reflects the time it took me to make this work and, to be quite honest, to feel comfortable with releasing this highly personal body of work to the public. Early in the process I showed some images to get feedback, but then went back to work very privately and quietly. I rarely shared any of these new images made after 2008. Last year, when Brian (Clamp) and I sat down to look at the work, he was surprised at the depth of the portfolio.

Untitled (Smoke) © Frank Yamrus

AL: It’s no secret that your newest body of work, I Feel Lucky, really results from—or at least was sparked by—a mid-life crisis. What role have the photographs performed, in the journey that you’ve made as you approached and passed the age of 50?

FY: As a photographer I don’t think I knew of another way to process this landmark event, so it was quite natural for me to reach for my camera and make these photographs. That very first impulse to take a picture felt unsurprisingly familiar and yet awkward, as I was not convinced I was ready to make work. However, once I made the first image, I was seduced, and the project began to slowly, but consistently, reveal itself. As I documented this journey, it gave me the opportunity to take another look at my life’s decisions and retrace my path to 50 as well as look beyond.

Initially, I made photographs about the “big” decisions, and some of those images feel appropriately iconic. As the project expanded, the “smaller” moments gave life to the narrative and helped me to see a more congruous life. Most of all, this process was empowering, as the images became cornerstones of my understanding, each image leading to another, creating dialogue to address the complexities of identity and life. Ultimately, I felt confidence and inspiration from these pictures and the response to this work has reinforced those emotions.

AL: Throughout the series, we witness the whole gamut of dispositions and emotions that you’ve experienced—humor, introspection, loss, joy, frustration, uncertainty, self-gratification, confidence—and yet, together, I Feel Lucky appears to be just a small glimpse of Frank Yamrus.

FR: Life is full and very complex. I agree this is but a glimpse of Frank Yamrus. Diane Arbus once said, “[a] photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know.” I subscribe to this sentiment and my imagery is, and has always been, about process and not about resolution.

The I Feel Lucky images, individually and collectively, inform. They are the evidence of life’s full spectrum of offerings: my hopes and dreams, my joy and sorrows, my happiness and pain, etc. And in spite of the filters of time and memory, the human desire to fabricate and stretch reality, these images feel authentic, and provide clarity and insight. Surely they capture the essence of my identity but, by no means, reveal all my secrets or truths.

Untitled (Boo Boo) © Frank Yamrus

AL: Does this survey of feelings, then, suggest a lack of answers, a lack of catharsis in facing up to and surviving a questioning of identity? Or would you say they represent an acceptance or acknowledgment of who and where you are?

FR: This survey of feelings is the very foundation of self-identity, and does not represent a lack of answers at all. As my personal history played out before the camera, these were the very elements that were the most closely scrutinized. I found this process to be emotionally rigorous and intellectually challenging, but in the end, oddly comforting and extremely rewarding. One of the many beautiful things about age is wisdom, and this investigation certainly uncovered the wisdom I acquired over my life’s journey. I was not looking for “answers,” although that in itself may be “the” answer. Fundamentally, I was interested in the evolution of identity. For example, two of the images I made for this series, Untitled (Lucky) and Untitled (Fountain), explore my relationship with my history and, ultimately, my identity in Provincetown.

In Untitled (Lucky) I’m disguised behind my shirt—not wanting to be recognized and not wanting to tempt fate—in this land that I once called sacred, that was my altar as I processed the loss of many friends. Sometimes I do not recognize myself in this reverent landscape under any other circumstances. Other times, when the stars are properly aligned, I embrace the entirety of that history confidently. My face is unmasked in Untitled (Fountain), as I mischievously glance at the camera and brashly spit a fountain of salt water. Fully exposed to the summery sunshine and brilliant blue water, I playfully seize the spirit of Provincetown and stake out my future in this land that holds my past.

AL: Provincetown is clearly of pivotal importance in your life. Why?

FR: When I made those landscape photographs on the Cape in 2004 that I referred to earlier, I wrote an essay about Provincetown that feels true to this day. “Provincetown is my home—it is comfort food and my favorite reading chair. It is the smell of a newborn’s hair or that moment when you first wake up in the morning snuggled against your lover. It is the place that offers me the intangibles: security and happiness, as well as the place for discovery, development, and ultimately a source of inspiration. I have spent endless summers in Provincetown but it is not where I reside. It is home, the place I visit, physically or emotionally, when I need a fix.”

Untitled (Sunset) © Frank Yamrus

AL: You published the series as a book. Do you see this as the ideal way for an audience to engage with the photographs?

FR: There a few things that I love about the book format for this project. First and foremost, the privacy and intimacy the book offers for these portraits is undeniable.

AL: One aspect of the book which works really well is that the photographs don’t appear to be arranged chronologically. It’s difficult to tell which image was made first and which last!

FR: Generally speaking, books tend to lend themselves to a linear read, which was not appropriate for this collection of photographs. With the I Feel Lucky book, I purposely avoided employing a chronological sequence. I was interested in creating an experience that reflected my non-linear process of examining, or perhaps more accurately, re-examining, these pivotal decisions and moments in my life. The dialogue created by the placement of the images was rooted in visual elements rather than related issues, feelings or chronology. This telling of my story had no beginning, middle or end.

AL: And as photographs, they’re printed at what, these days, is considered small-scale—measuring 20 x 28 inches. What determined the scale?

FR: As we all know, size matters, and for this work, this issue of scale was a delicate balance. My gut reaction was to make small prints to keep with the notion of private moments. I’m a fan of small images, and love the physical act of walking up to an image in order to digest it. However, I usually experiment with image size, and as I scaled-up the images from 5 x 7 to 10 x 14 and then finally to 20 x 28, these images came alive: facial details, gestures and background information commanded attention.

Another consideration, of course, was how the photographs would work in a gallery. My goal was to create a group conversation with the images, and as visitors walk into ClampArt they can hear the internal dialogue. At least I can. Image size and the density of the installation contributed to this success. When I took the 20 x 28 prints to the gallery, I felt this size met this goal and was happy that I was not printing on a larger scale, which oftentimes demands more visual space between the images.

Untitled (Disappear) © Frank Yamrus

AL: It’s interesting, too, that in a number of the photographs you’re not alone. Different people come into the frame and you provide little indication of their place in your world.

FR: The importance of my relationships was integral in my understanding of self. Although I don’t identify the people in my pictures, they are truly part of my life—sometimes playing themselves and at times playing others.

Untitled (Disappear) was constructed around the notion of anticipatory loss. As Sunil Gupta writes in his essay Everyman: Frank Yamrus, “Untitled (Disappear) is chilling. It evokes an insoluble mystery, a doubt that will linger forever. The nocturnal blue and the closed eyes remind us of impending gloom. This is a moment of recognition that a shared intimacy is no more. The image is more a requiem of a relationship than an image of the relationship itself.”

I don’t believe you need to know that the model in bed with me is Larry—my long-term partner of more than thirty years—to understand the significance of this photograph. In Untitled (Red), Lucas, a new love, serves as my model, but the image is more about a disconnect—anonymous sex and fetishism—than about our relationship.

In Untitled (Brooke) and Untitled (Stone), my models allowed me to explore the notion of fatherhood and visualize myself in a role that feels so completely foreign to me. The comfort I needed to make these pictures feel real was dependent on my close relationships with these models.

Lastly, in his essay The Borrowed Mirror, Bill Hunt addresses an image of me and my dad and insightfully captures my use of others in these photographs. He says: “Untitled (Dad) combines the dimensions of reality and fantasy effectively. The figure in the snapshot is less important than our sense that Yamrus’ search for meaning is entirely framed in this mirror. It is an image of reflection, handsomely and thoughtfully composed.”

Untitled (Dad) © Frank Yamrus

AL: Those who have followed your career for some time will recognize in this body of work, references to earlier photographs. Was this something that you consciously sought out?

FR: Yes, one of the underlying relationships that exist throughout this series is my relationship to photography, and my own work became fodder for this series. Being a photographer is a crucial part of my identity, and quite naturally referencing my own images became part of this process.

For example, I spent eight years in the moors of Provincetown making work about the loss of many friends to HIV/AIDS. I played off those images, that time, and my relationship to Provincetown throughout this series. Untitled (Sandman) and Untitled (Cemetery) are two examples. This tribute not only reflects my deep fondness for this place but also the importance of that time in my life and its impact on my career.

Untitled (Sandman) © Frank Yamrus

AL: Some will argue that self-portraiture is generally understood as the domain of the female artist. As a male, do you bring something different and new to this genre? If so, what is it that?

FR: I believe this argument has strength if we look at the genre in more contemporary terms; however, now we must consider the recent proliferation of self-portraits created for social media and how these pictures are shaping the complexion of this debate. Who hasn’t taken one or a hundred pictures of themselves to post on Facebook? However, my intention was to jump into this conversation with the same brutal honestly and raw vulnerability that I’ve noted in self-portraits made by women photographers. Even though my series is a blend of documentary and fiction, reality and fantasy, there is no denying its candor, humor and honesty. For me, that is what feels fresh about this work.

AL: From the point of view of commerce, do you feel there’s a place in public/private collections for these images? What transition, as an artist, have you made by placing highly personal images into the public domain—by way of the book and an exhibition?

FR: A number of these images have found their way into public and private collections, so my answer is a resounding “yes.” Although these images represent personal moments, I believe they also have a universal appeal as evidenced by these acquisitions. I generally don’t think about commerce while I am making work. But once it’s done, the work needs to find an audience. Sometimes this task is more challenging than making the work itself!

With respect to transition, I’m not quite sure enough time has transpired for me to answer this question. Initially, as I stated earlier, I was a bit skeptical about putting these images on public view, but thus far, I’ve received tremendous support. For the most part, I’m objective about the images as single pieces, however, collectively, as a body of work, I’m still attached. Interestingly, this attachment does not feel any differently than it did with other bodies of work I’ve created. Perhaps in years to come, I may feel differently about putting my face, my body, my being on public view but it’s much too early to tell. Although this work feels complete, I’m certain I will add pieces here and there. Who knows, I may go through this process as I approach 60. Right now, I’m ready to move on.

Untitled (Chapstick) © Frank Yamrus

AL: You seem to have survived 50! Do you really feel lucky and what are you moving on to?

FR: I do feel lucky, grateful and at the moment tired. The exhibition preparation and book were very consuming over these past 18 months. Next, I Feel Lucky moves to the Albert Merola Gallery for an exhibition, which will feature the images made in Provincetown, to kick off their summer season on May 18th. After that, a well-deserved vacation, perhaps some romantic walks on the beach taking corny pictures of sunsets and if my luck holds out Penelope Umbrico will find these pics on Google and incorporate them into one of her typologies! As far as new work, I’m interested in exploring my new hometown, New York, and its people.

Frank Yamrus lives and works in New York. In February 2012, I Feel Lucky was a solo exhibition at ClampArt in New York City coinciding with the publication of the accompanying book. I Feel Lucky will next be exhibited at the Albert Merola Gallery in Provincetown, May 18–June 7, 2012.

Tags: ClampArt, Frank Yamrus, I Feel Lucky, Klompching Gallery, Photography

Posted in Photography | No Comments »