at Length

James Pomerantz

photography by James Pomerantz

interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

Fishermen with a USA flag they found in the Caspian Sea, Nabran. From the series Caspian Dreams.

At Length: You originally studied mathematics and philosophy, what inspired you to become a photographer?

James Pomerantz: I enrolled in a photography class as an elective at Columbia University, Tom Roma was the teacher. He brought photography to life for me. Class discussions weren’t about focal lengths or apertures—they were about poetry and emotion. Until then, I had never seriously looked at photographs or considered them as more than simply illustrative. I fell in love with photography because of that class.

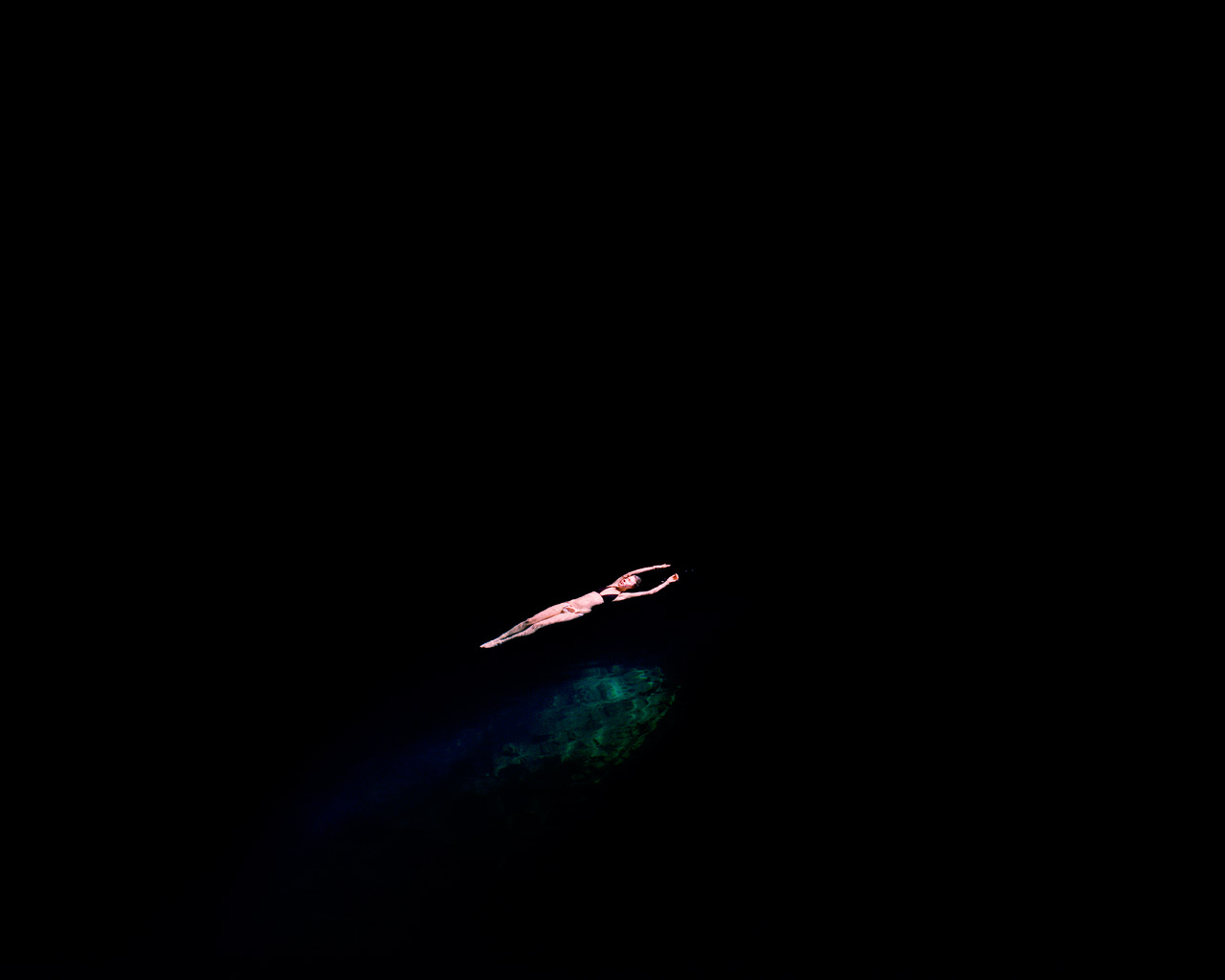

A man floats in a mineral bath on the beach near the oil fields of Bibiheybat. From the series Caspian Dreams.

AL: You have spent a good amount of time photographing in the Caucasus. How did you get interested in that area and what brought you there?

JP: I had spent time in Asia, Africa, The Middle East…all the places I felt compelled to explore as a young photojournalist. While they were all interesting, I never felt a connection to any of them. I thought I would give the Caucasus a shot. I had seen Rena Effendi’s photographs from Azerbaijan—there was something about the faces in her portraits that intrigued me. She had also stated that she felt that Azerbaijan was photographically a black & white country—I was curious about what she meant. My plan was to go to Azerbaijan and produce a photo essay about the oil industry there. It also didn’t hurt that I had heard that Azerbaijan has amazing kebabs—I used to be a cook and I’d be lying if I said that food doesn’t play into my travel decisions.

High school graduate and friend in Baku, Azerbaijan. From the series Caspian Dreams.

AL: What are the underlying questions or issues that you are exploring in documenting that region?

JP: Within a few days of landing in the capital, Baku, I forgot about oil and just wandered. I found myself relating on a personal level to what the country was experiencing 17 years after the fall of the Soviet Union. I remembered what I was like at 17—awkward, unsure, trying to figure where I fit in my world. Of course, I was projecting my own history onto the region, but I don’t have a problem with that. The work that most moves me is the result of a collaboration between the artist and subject, a sort of symbiosis. My work from Azerbaijan isn’t objective by any means and is as much about me as it is about the country and its people.

A destroyed cable car in Tkvarcheli, Abkhazia. Once a mining town with a population of over 20,000, the war saw the closure of almost all local businesses and now less than 5,000 people remain. From the series The Balance of War: Abkhazia.

AL: Caspian Dreams and The Balance of War: Abkhazia deal with upheaval and transition. What are the connections between the two projects and what were the key challenges of working on these?

JP: While both projects are personal, the work from Abkhazia was made for the World Press Joop Swart Masterclass. As part of the weeklong workshop, we had to prepare a photo essay in advance that revolved around a word that they provided. The word we were given was “balance.” The two projects are aesthetically similar as I made the Abkhazia work shortly after Caspian Dreams and both projects share that same post-Soviet, Caucasus color palette. There were additional challenges to shooting in Abkhazia—it is still a disputed region occupied by Russian forces. I had an Abkhaz press card, but that didn’t mean a thing to the Russian soldiers. I was also in Abkhazia at a fairly tense time, just a few weeks before the 2008 Russia–Georgia War. It seemed to make sense to go to Georgia and Abkhazia after Azerbaijan—they’re neighbors. At some point, I would also like to visit Armenia.

Young refugee and cat, Tskaltubo, Georgia. From the series The Balance of War: Abkhazia.

AL: Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, there have been many photographers documenting various aspects of life in the republics—such as Stanley Greene’s Open Wound, Simon Roberts’s Motherland, and Andrew Moore’s Russia—to name just a few. Do you feel there is a trend for Western photographers to pick up on the subject? If so, what’s your view of that and where do you view your place within it?

JP: The collapse of the Soviet Union was an historic event that had a global impact. Many of the countries that gained independence as a result are now in an interesting stage of development. When I was in Azerbaijan, it had the fastest growing economy in the world because of its oil. But, there were also hundreds of thousands of displaced people living in terrible conditions as a result of the Nagorno-Karabakh War. It was an interesting time to be in that part of the world. The three bodies of work you mentioned are so, so different in content and form. The Russia–Georgia War did result in a lot more coverage by foreign press for a short period of time and Magnum recently released their book Georgian Spring but I wouldn’t say there’s any sort of trend to pick up on the subject. The Soviet Union was almost 2.5 times the size of the United States but the countries in the region are still much less covered than many others.

Refugee wall, near Kutaisi, Georgia. From the series The Balance of War: Abkhazia.

AL: How would you characterize your visual style and approach?

JP: It varies. Sometimes I like to work very fluidly, without much of an agenda—it’s a great feeling to just wander and discover. At other times, I’ll make a shot list of things I’m looking for—it all depends on the project. I think there’s often a lot of pressure to specialize, to have a particular style and to remain consistent from project to project. I would much rather vary how I shoot to suit the subject than try to shoehorn the world to fit a limited style. Right now I’m working on one project with webcams, another with a point and shoot and another using large format.

Refugee, Lenin, Marx and Engels, Tskaltubo, Georgia. From the series The Balance of War: Abkhazia.

AL: You’re currently in the MFA program at the School of Visual Arts. Why did you decide to go back to school?

JP: I went back to school hoping to accomplish the following:

1. To strengthen my technical skills. Prior to SVA, I knew very little about lighting and post-processing.

2. To strengthen my understanding of contemporary photography and the history and theory behind it.

3. To be a part of a community that revolves around rigorous critiques with established artists and equally curious peers.

My hope upon graduating is to continue my shift from the magazine and newspaper world to the fine art world. I would also love to teach. An MFA is helpful for both.

AL: As a photographer with an established track record, you’re studying alongside a number of people who have yet to build their careers. How are you finding that?

JP: Everybody brings something different to the table. A professional career doesn’t have all that much to do with having an ability to appreciate photography or to provide insightful feedback. Many of the other students studied art as undergraduates and know far more than I about Renaissance art or Greek sculpture or architecture or digital imaging or lighting—their feedback is priceless. All that matters is that they care about photography and are curious. A career in photography is more about business and not the act of photography itself. I really appreciate the purity that there is at school, it’s not about magazine assignments or contests or sales or shows. It is about learning and experimenting and having fun.

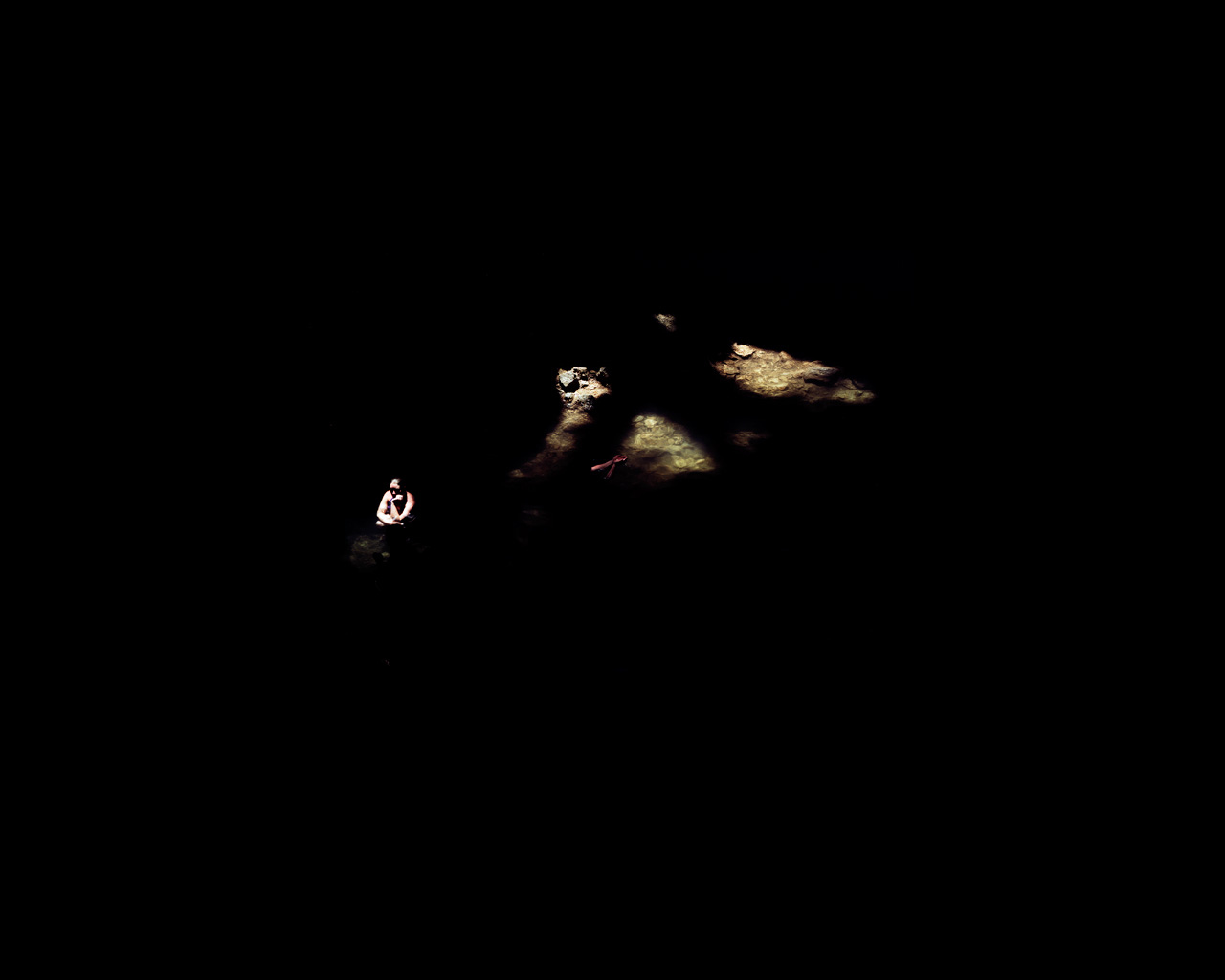

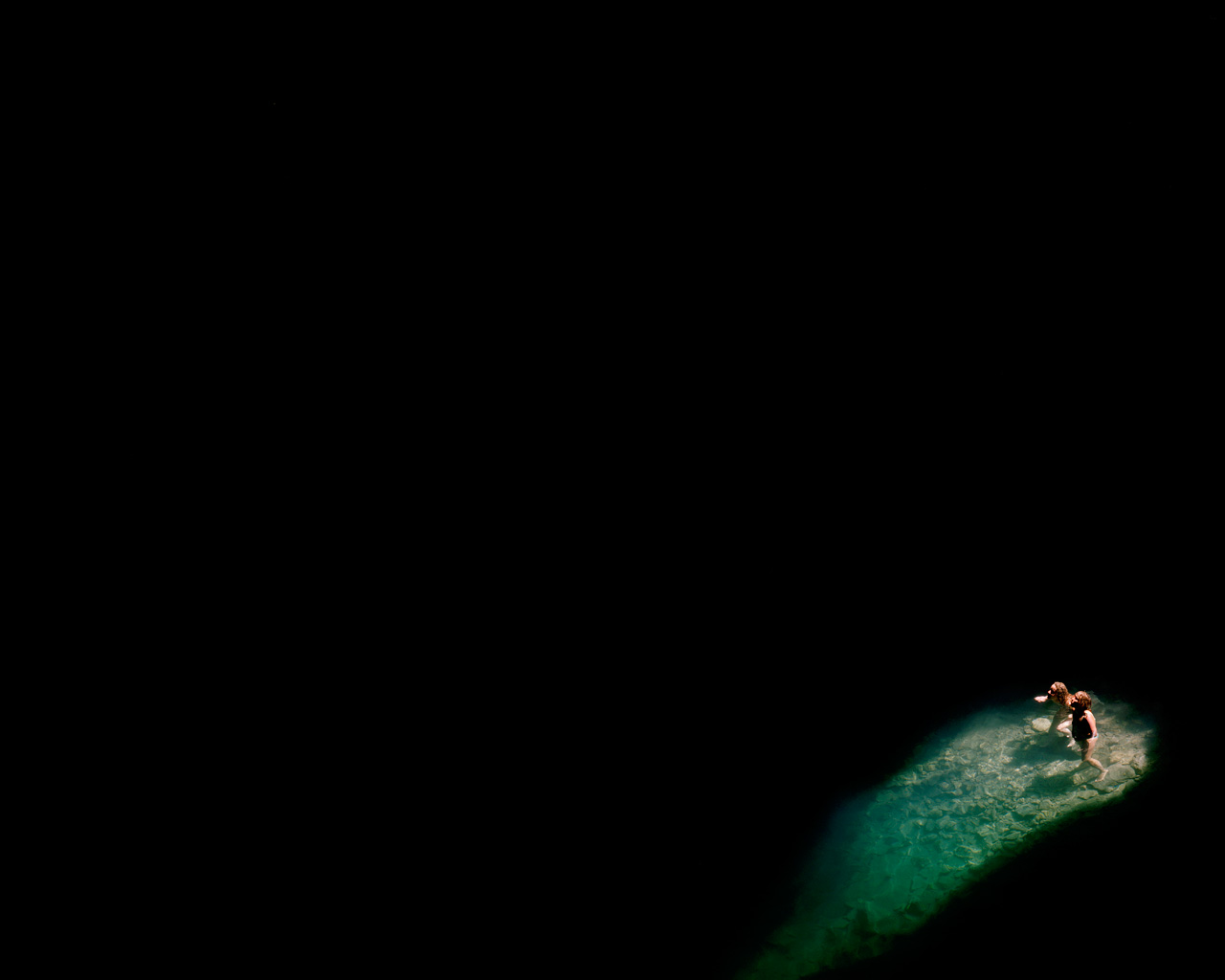

From the series Agua Sagrada.

AL: Whilst you’ve been in school, you’ve been signed to Institute for Artist Management. How is that working?

JP: Well, so far so good. It’s an amazing group of photographers. The people running it are open-minded and looking to explore new ways to promote the artists and their work. I’m very excited to be a part of it!

AL: You’ve shot for magazines and know that the past year has been challenging for the print industry—with many notable magazines and newspapers shutting down. There has been talk of the “Death of Print”—or at least its rapid decline. In this context, do you feel a need to alter your approach once you’ve completed your studies and re-enter the photography field full-time?

JP: I think that a working photographer in the 21st century needs to be as diverse as possible. Know how to work with still and the moving images. Know how to use all of the available software out there. Keep an open-mind. There are photographers like Jason Eskenazi, Rob Hornstra and Stephen Gill who are self-publishing wonderful books. There are storytellers like Tim Hetherington who are working with whatever medium is most suited for the task at hand. There are artists like Broomberg and Chanarin, Simon Norfolk and Luc Delahaye who are referencing traditional paintings in their photographs and merging the language of fine art and photojournalism. I want to be as educated and versatile an artist as possible so that no matter what happens in the print industry or the fine art world, I can continue making work that I care about and that I hope has relevance to the world.

From the series Agua Sagrada.

AL: You’ve been chronicling your time in school on your new blog A Photo Student. Why are you doing this and what kind of responses have you been getting?

JP: I started the blog as a resource for people considering MFA programs. When I was looking at schools, I was unable to find much information about the various programs. I wanted to provide a window into the day to day of a photo MFA program. As the blog has developed, I’ve realized a few other benefits. The blog lets me write, curate, critique, teach and learn all at the same time. It also lets me maintain some of the relationships I’ve developed in the past few years while I’m locked away in school! It’s also my photo diary. Years from now, I’ll be able to look back at what work I appreciated, what I was reading, what issues I was wrestling with…

It’s a ton of work but I think it’s worth it. The feedback has been 99% positive with a few comments about how education in the arts is a waste of time or how theory is meaningless. I think general, sweeping statements are pretty meaningless.

From the series Agua Sagrada.

AL: Last June, some of your Agua Sagrada work was included in the Summer Show at the Bonni Benrubi Gallery in New York. The work seems to be quite a departure from your previous work. Can you tell us more about the project?

JP: The work was made in a cenote in Mexico. Cenotes are underground fresh water sources. For the Mayans, they were also places of spiritual importance. Not only were they the sources of their drinking water but the Mayans also often performed various religious activities around the cenotes. Today, cenotes are visited by tourists who pay to swim in the cool water. The work is different from my previous work but I think that’s a reflection of my state of mind at the time I made it. I made Agua Sagrada before I had committed to going back to school and it was during a period of dissatisfaction with the work I had been making. My first trip to the cenote was also made the same week I proposed to my fiancée, so it was a period of contemplation and transition.

I sat on a ledge in the cenote and photographed people interacting with the single shaft of light that entered through a hole in the cave ceiling. It was a comforting body of work to produce and I intend to go back. Again, I shoot differently depending on the subject. For Agua Sagrada, I wanted to emphasize the spiritual relationship between the bathers and the light. Their gestures and body language take on new meaning in the photographs. Just as in Azerbaijan, the photographs are just as much about me and what I felt as they are about what I saw.

AL: Where do you see your work going from here?

JP: I’m interested in exploring the ever-shifting line between documentary and art. I’ve been feeling a bit goofy lately so I think I’m going to work on some funny projects. I think my most successful work has embraced the quirky so I want to see how that develops. For some reason people think that humorous work shouldn’t be taken seriously—I really appreciate artists like Tim Davis, Martin Parr and Stephen Gill. It would be nice to make people laugh and think.

To see more work by New York-based photographer James Pomerantz, visit his website. You can also follow his blog A Photo Student—an insightful chronicle of his adventures back in school, as well as additional observations on photography in general. James Pomerantz is represented by Institute for Artist Management. All images © James Pomerantz.