at Length

Posts Tagged ‘Fresh2015’

Kimberly Witham

Tuesday, January 24th, 2017

interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

Pears © Kimberly Witham

At Length: How long have you been photographing and what originally inspired you to begin?

Kimberly Witham: I came to photography through a rather circuitous route. As an undergraduate, I studied Art History. Modern and contemporary art were my focus, and I often wrote about photography. The Serrano “Piss Christ” NEA scandal was happening at the time, so photography was really in the news. After some graduate study in Art History, I decided to switch my career path. I wanted to be a ‘maker’ instead of a critic. In retrospect, it makes sense that I gravitated towards photography, but at the time it was just something that interested me. I started making pictures more seriously about 15 years ago.

AL: Your practice seems to involve two key elements – the still life and dead animals. Were these two elements intertwined from the beginning or did one offer a special fascination?

KW: My still life fascination most likely comes from two sources – my mother is Dutch. I grew up surrounded by a very Dutch world-view and aesthetic. My studies in Art History furthered this fascination. I have always been interested in how images are interpreted. In particular, traditional Dutch still life paintings have intentionally coded meanings.

I have always been attracted to animals and natural history as well. Growing up, we had dogs, cats, horses, chickens, etc. I have always loved natural history museums, birds’ nests, animal bones, you name it. Ultimately, my interest in still life and my interest in natural history collided. My early work includes both still life and landscape. The animals came later, once I moved to the suburbs.

AL: The dead animals you use in your artwork originate as roadkill? Do you go out looking for them?

KW: No. The creatures in my images are found during my daily journeys to work, the grocery store, etc. I am very alert to the side of the road when I travel, but I never cruise around looking. Sadly, I do not need to go out of my way to find dead creatures by the roadside. I am always prepared to stop – I keep plastic bags of various sizes and hand sanitizer in my car. I also have a hack saw for deer antlers . . .

Raccoon © Kimberly Witham

AL: We understand that you learned taxidermy. Why did you do this and how does it affect your photographic and creative process.

KW: I learned taxidermy at the American Institute of Taxidermy in Boulder Junction, Wisconsin. I only studied small mammal and bird taxidermy, as those are the creatures I tend to find. Fish taxidermy is rather complex and holds no appeal for me! I was the only woman, and the only non-hunter in my class. Although I think I was a bit of a novelty to my classmates, they were very good-natured guys. When I did not run away screaming, I think I earned their respect.

In many ways, I consider my still life photos to be documents of sculptural constructions, which exist only for a brief time and only for my eyes. I wanted to find a way to make more permanent manifestations of my still life constructions. Taxidermy seemed like the best way to achieve this goal.

Although I am far from a scientist, taxidermy also allows a greater understanding of the muscular and skeletal systems of the animals I encounter.

AL: Which animals are hardest / easiest to manipulate and work into the images? Do you have favorites?

KW: I have a few pieces with baby deer. While they are small for deer, they are not ‘small’ – somewhere around 40 lbs or so. Due to size and weight they are the hardest to work with. Birds are the easiest, as they are so small and light. I don’t have favorites. Frankly, I would be happy if I never encountered another roadkill creature again. The creatures I work with are simultaneously incredibly beautiful and totally heartbreaking.

AL: Do you make a still life to work with the animal or vice versa?

KW: The whole process happens very organically. To some extent, I am forced to work with the pose the animal died in – rigor mortis is not forgiving. That being said, I do have sketches of ideas inspired by paintings, daydreams, etc. They often include a specific type of animal. More often than not, the photo I think I am going to make is not the one I end up with. I have a studio filled with props, tables, seed pods, skulls, dishes, fabrics, you name it. I just start moving things around to see what will happen. It generally takes a day to make one photo.

Squirrel © Kimberly Witham

AL: ’Of Ripeness and Rot’ was selected for the Fresh 2015 exhibition at the Klomching Gallery. How have these photographs developed from your earlier work?

KW: Prior to beginning work on ‘On Ripeness and Rot’ I created a series of still life images titled ‘Domestic Arrangements.’ These images include roadkill creatures and household items, but the aesthetic was much more bright, colorful and playful. I made these images in response to encountering lots of roadkill after buying a house in the suburbs. I was spending my evenings painting and remodeling an old house, and my days driving to work and picking up roadkill. I often joke that in making ‘Domestic Arrangements’ I was imagining myself as the love child of Martha Stewart and Carl Akeley (the father of modern taxidermy).

As I was finishing that project, events began to unfold in my life which made me think about mortality, beauty and fecundity. The darker aesthetic of ‘On Ripeness and Rot’ developed from that point.

AL: The reference to the Dutch Vanitas is very evident. How would you say you’ve developed this form of still life, and made it your own?

KW: Gosh, that is a tough question. Vanitas paintings referred to both the beauty of the physical world, and the looming threat of death and the afterlife. My images use this age-old visual language, but reference very contemporary conditions (roadkill is a modern problem, after all). My images are more pared down. I have always been a strong believer in the ‘less is more’ adage, and many traditional still life paintings are too over the top for me. I prefer to be more subtle, perhaps because I am dealing with such sensitive materials.

AL: Your images portray great depth of color, are obviously very well conceived, quite restrained – suggesting a detailed and determined process of making. Can you tell us something about how you make the work?

KW: Solitude is everything to me. My studio is quiet – no music, no distractions. Almost all of the images from ‘On Ripeness and Rot’ were made in my old studio, which was the enclosed sun porch on my house. I use naturally light and minimal tools—a few pieces of white foam core to bounce light, a tripod, and a camera. I work slowly and methodically. I find myself moving objects by fractions of an inch to get everything in the ‘perfect’ spot. Color and texture are important elements as well. As I said before, my studio is filled with fabric, objects, etc. and I spend a lot of time looking, thinking and rearranging. Sometimes it just doesn’t work, and I end the day with nothing. Other days it comes together immediately. When I finally have the image, there is always this brief moment where I look through the lens and just gasp for a second.

My family and I recently moved to a new house with more land, and an outbuilding studio where I can lock myself away in silence, even when everyone is home. I am still getting set up. It takes a remarkable amount of time to unpack a studio with so many props.

Hanging Birds © Kimberly Witham

AL: The symbolic use of the dead animals is consistent with the concept of the Vanitas, but you are careful to incorporate them in an understated and quiet manner. How do people respond when they realize what they’re looking at?

KW: I am conscious of the fact that I am walking a fine line. I intentionally avoid using creatures which are mutilated or grotesque. It is important to me that my images show reverence for the creatures pictured, and the natural world as a whole. Most people see that reverence in my images (admittedly, some do not). Many people initially assume that the creatures have been placed via photo-manipulation. Once they understand my working process, the most common questions are “do you where gloves?” and “what do you do with the animals once you have made the photo?”

AL: Are there aspects of the photographs that you intend to be evident, that are perhaps overlooked by viewers? For example, is there a very slight and quiet amount of humor?

KW: There is a vein of dark humor which runs through my work. It is somewhat more evident in ‘Domestic Arrangements,’ but it’s also present in ‘On Ripeness and Rot.’ There is something quite absurd about photographing roadkill, delicate tea cups and flowers in the same frame. I think this absurdity is evident in many of the images.

AL: The scale of the work is quite small, intimate, which ties in with the restrain of visual expression. Tell us about how the size relates to the image.

KW: I don’t want to emphasize theatrical and/or grotesque qualities in my work. I think the scale of the prints also references the way in which they were created. Smaller prints are more intimate, intended to be viewed by one or two people at a time. One is required to be physically closer and to slow down to really see the image. The friction between beauty and revulsion is important to me. I like the idea that a viewer will be attracted to the light and color in the work while viewing from a ‘safe’ distance, and will only notice the disturbing parts once they have come close enough to really see.

AL: Has this work been placed into any notable public collections? Where do you see it living/existing?

KW: One of my pieces was recently acquired by Lehigh University for their photography collection. Other than that, my work resides in many private collections. When I make the work, I don’t really think about where it will ultimately go. I need to make the work that is on my mind and just hope that someone will want to own it. I am always touched when the work resonates with a viewer. I see my work within the context of both art and natural history.

Fall Fruits © Kimberly Witham

AL: Which is your favorite image and do you have it hanging on a wall (which wall)?

KW: I once heard an expression about artists—that their favorite pieces are the ones they are about to make. I can’t say I have favorites exactly, but there are images which continue to resonate with me – I find myself thinking – “wow, I made that?” I am still in the process of moving into my new home, but I do have a print of “On Ripeness and Rot #10 (raccoon)” ready to hang on the dining room wall. That photograph is an ode to Jan Weenix, a Dutch painter I love. The image expresses abundance and decay in equal measure. It reflects my current mind set well. I also have work by many other artists in my home. I have some of Sarah Sudhoff’s pieces (we traded years back). I also have a portrait of Francesca Woodman, and a really beautiful sculpture by a former classmate of mine, Petra Kralickova.

AL: Are you now working on new artworks to add to the ‘Of Ripeness and Rot,’ or are you now developing the next installment of your practice with something new?

KW: Both. The past year has been very chaotic for me. My father passed away unexpectedly in April. In August, I moved to a new house and studio, complete with 5 acres of land to wander and explore. When in chaos, I tend to become even more introspective. I have been sketching some images based upon the still life tradition of the ‘laid table.’ While it may sound like a small change, I am trying to work with a horizontal composition and a greater density of objects. Additionally, I was recently re-introduced to the work of the American painter Charles Sheeler. Some of his paintings were included in the really excellent American still life exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Sheeler was both a painter and a photographer. His work is clean, spare and minimal while at the same time quite intricate and beautiful. For some reason, I find Sheeler’s work to be completely seductive at this moment—perhaps I am seeking order. I have about 5 new images, working with this spare aesthetic, with plans for several more.

Kimberly Witham‘s solo exhibition, ‘Reap’, is on view at the Filter Photo Space in Chicago, January 6 – February 17, 2017.

Tags: at length mag, contemporary photography, dutch still life, filter photo space, Fresh2015, kimberly witham, Klompching Gallery, of ripeness and rot, photographer interview, taxidermy, vanitas

Posted in Photography | No Comments »

Bill Durgin

Wednesday, November 2nd, 2016

interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

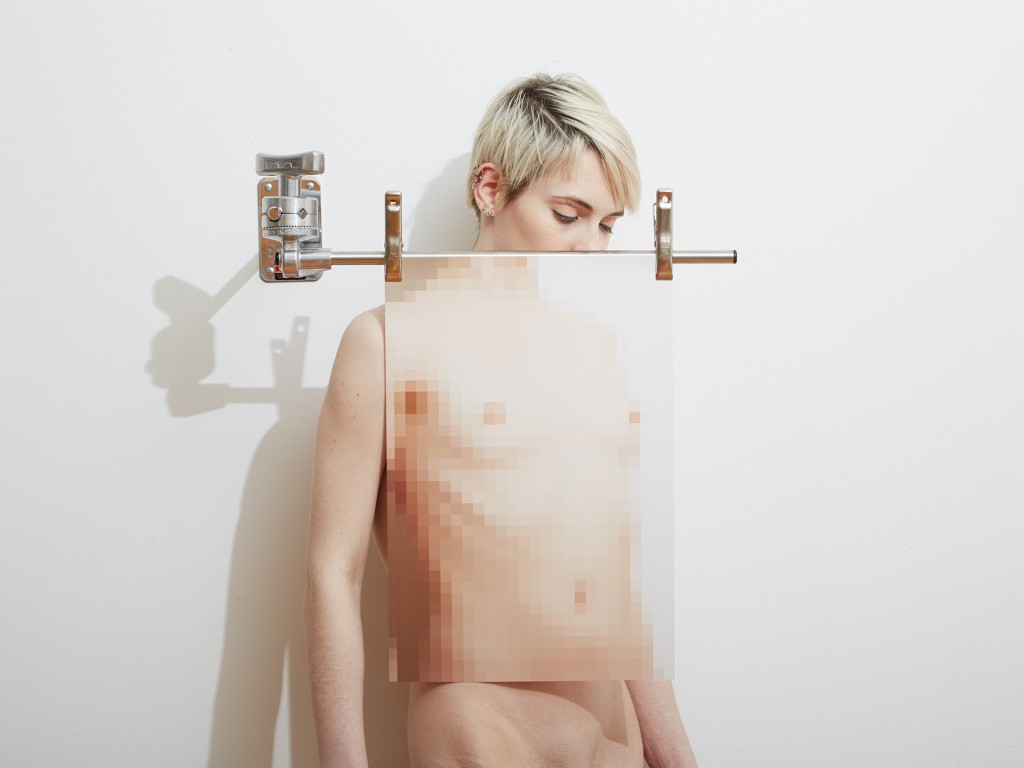

Adrian With Mosaic, 2015 © Bill Durgin

Adrian With Mosaic, 2015 © Bill Durgin

At Length: Your photographic practice, as a whole, engages with the human body. What initially inspired you to make this the focus of your practice?

Bill Durgin: I’ve always been fascinated by how the physical body how ages, the virtuosity of athletes, dancers, performers, and just how people inhabit space. For years I was reluctant to photograph the body as I wasn’t interested in the figurative photography work I’d seen. While working on an earlier series of narrative-based images, I became less fascinated with the before and after of the scene I was creating and more interested in creating something singular, something that did not have a before and after, something that existed only in one frame. It couldn’t be perceived as part of a scene that you would come across. This idea came to me of a torso draped with no arms or legs. I wanted to see if I could image that. I’d originally thought I would have to do it in postproduction, but while working with a friend who is a dancer, I realized how through contortion and perspective I could create this sculptural view in camera. I was hooked.

AL: The Fresh 2015 exhibition featured photographs from the “Studio Fantasy” series. Can you tell us more about this work—especially in terms of how it emerged from your previous series?

BD: While I was an undergrad at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, I saw a television ad for Lagerfeld Photo eau de toilet. It showed a photo session in a shabby chic loft with a stereotypically beautiful model shooting with a stereotypically handsome photographer, no other production staff. Shot in black and white, very diffused, the shoot was a flirtatious dream sequence. At the time I was working in commercial photo studios and the school’s darkrooms, sweating, getting dirty, smelling of chemicals, schlepping equipment, enduring the demands of anxiety-inducing production schedules…. I loved the irony of it, seeing the photographic shoot portrayed as fantasy while working in its much less glamorous reality.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pbS2ha5IQLY

I was reminded of this while shooting head shots for a friend. He brought a bottle of wine and offered me some. While I do love wine I can’t drink while I shoot and said so; there are too many variables to focus on, and I’ll inevitably mess something up. He was surprised and said he had a completely different picture of what I did on a daily basis. When I realized that even my friends had this fictionalized glamorous view of my studio practice the idea for Studio Fantasy came immediately. Unlike other series the name came first, and I started showing the edges of the sets and some of the banality around studio practice. In my previous bodies of work I carefully composed each image to avoid stray objects and supports. This series put those in the forefront. I wanted to depart from the set of rules I had laid upon myself, freeing up my technique and exploring some new ideas while still investigating new ways of imaging the body.

Fake Wine Spill, 2015 © Bill Durgin

Fake Wine Spill, 2015 © Bill Durgin

AL: In this body of work, you have maintained the human form as a central focus, but also incorporated photographs of objects without bodies. Why is this?

BD: Still lifes in the series are about making the banal beautiful, elevating studio tools and props to be the primary subject. Using gaffer tape to make a graphic tonal composition, the beauty of a plastic bag suspended from a C-stand, apple boxes leaning against each other with a print that visually erases one, a fake wine spill shot to reveal its inherent farce.

AL: In many respects, then, the studio, along with its various props, has emerged as a key subject. Can you tell us more about how you’ve explored this?

BD: “If I was an artist and I was in the studio, then whatever I was doing in the studio must be art.” – Bruce Nauman

The studio, specifically my studio, is the key subject in this series. Aside from the obvious titular reason, I’ve been interested in the labor of studio practice. I have always revered Bruce Naumans’s approach to working in the studio, going there everyday working through the boredom of being alone all day and making that the work. Also his approach to creative blockage, “It generally goes back to the idea that when you don’t know what to do then whatever it is you’re doing at the time becomes the work.” – Bruce Nauman

I use the studio as a blank slate from which to build an image. There were certain rules I set as my work working method: show edges of the set or parts of the studio, use minimal props, a single bare bulb light source, include any tool used including color charts. I start with an empty studio area and bring in whatever support catches my eye that day. When working with a model, I’ll direct them to where the focal point is and then we’ll improvise and refine a pose. I’ll then take part of that image, pixelate it, print it, then bring that back into the set and continue improvising and refining.

Priscilla With Color Checker, 2015 © Bill Durgin

Priscilla With Color Checker, 2015 © Bill Durgin

AL: It’s not just the studio that you examine, but this notion of the photographic space as well. What visual devices have you employed to examine these ideas?

BD: The camera itself is an editing tool; you are creating a visual space and omitting anything outside of the edge of the frame. The lens has a singular monocular view, which I exploit to achieve my composition, showing and hiding parts of the studio, the set, and sometimes the figure. “Studio Fantasy” is about making a photograph, not a documentary of what happens during the shoot.

I was looking at a lot of sculpture throughout this series. While I do see much work in person, I would always be looking at photographs of it in my studio. I was taking inspiration not just from the sculptures themselves but how they were translated into the photographic space. I treated my sets as a sculpture and documented them from a very specific perspective.

AL: The use of the pixilation appears to be a nod toward contemporary image consumption, through platforms such as social media, for example, but we wonder if there is something else going on. Can you expand on this element of the work?

BD: I saw an image on Instagram where someone had pixilated part of a body to fit the Community Guidelines. I was drawn to how the image looked more like a beautiful collage than a censored image. I could never find the image again, and perhaps it’s just the memory of that image that inspired this direction. I was drawn to the idea of using a form of censorship as a tool for incorporating a different dimensional plane within an image, like a collage. It also became a new way of abstracting the body and calling attention to the aspect of nudity rather than hiding it. The viewer becomes very aware of what is seen and what isn’t.

AL: How do you want your work to be received or understood in this context?

BD: I want the pixilation to be seen as a form of collage. I first saw it used in television news as a way to keep persons and incriminating documents anonymous. It was also sometimes used to hide nudity, often streakers at sporting events. Now I see it most often used on social media for the purpose of obscuring nudity, especially on Instagram. While I use it as a compositional tool, I also enjoy that it references anonymity and censorship.

Jen With Mosaic, 2015 © Bill Durgin

Jen With Mosaic, 2015 © Bill Durgin

AL: Overall, your practice presents itself as disciplined, formal, rigorous. How do you go about making what you do? What is your process?

BD: I usually start with a bare studio and an idea. That idea could be a sculpture I saw, a pose in a painting, a new piece of equipment in the studio, or just a piece of plywood leaning against the wall, and more often than not it is a combination of props and a pose. This idea is a launching point, something to set up before the shoot begins. When I get on set with the subject, a model, prop or myself, improvisation takes over. I select an area to be pixilated, print it out and bring it back into the set when improvisation takes over again. I’ll often have to do several prints, try different supports, a constant back and forth between staging the new set and improvising with it.

AL: Do you view your practice as a formal interrogation of the subject? If so, what are the key qualities or concerns that thread the different bodies of work together?

BD: My work is more of a personal interrogation of the subject(s). While there are definitely formal issues investigated, representation, figuration, compositional strategies, theories of perception, there’s also very personal motives and emotional content within the images. I’d say that the main elements that go through all my bodies of work are image construction and a constant push for the new ways to image the body through various formal and personal perspectives.

AL: Would it be fair to say that the “Studio Fantasy” series interweaves several theoretical/conceptual notions? For example, the photograph as constructed and mediated, the labor of the hand, scopic illusion and so on?

BD: Definitely. Since the beginning I’ve always focused on constructing photographs; it’s just what I’ve been drawn to do, and with each body of work a new set of concerns gets added: historical context, both photographic and art historical; the use of camera angle and perspective, and the gaze created by that perspective; studio labor; body image; photographic space as partial truth. Some images address more concepts than others, and “Studio Fantasy” brings in ideas of creating images in a digital age while the construction of those images finds its core in hands-on studio technique.

AL: The color palette of the series is very restricted, why is this?

BD: I wanted the studio to be the ground from which these images emerged, so that determined the palette. Being a minimalist, adding color wasn’t a concern. I guess my studio just isn’t very colorful.

Self Portrait, Gray Card and Multiclip, 2015 © Bill Durgin

AL: It’s also somewhat quieter than your previous work, less risqué. Do you think this helps to make photographs more accessible and palatable to art collectors? Or, if this not a concern or conscious shift?

BD: I actually thought this work was more risqué, bringing the topic of nudity right to the front. Perhaps the bodies are more recognizable, but there was no conscious effort to make anything more palatable. I wasn’t thinking of sales while making it, just ideas and experimentation.

AL: Following the Fresh 2015 exhibition, you were shortlisted for the Aperture Portfolio Prize. What impact has this exposure had on your success as an artist, and what is next on the horizon?

BD: It was an honor to be in Fresh 2015 and shortlisted for the Aperture Portfolio Prize. I definitely had a bump in exposure, but most of all it is validating as an artist to be recognized for your work. This was a new direction for me, so it has encouraged me to continue expanding, growing and experimenting with my work. Right now I’m working on a series entitled “Figure-Ground,” stemming from the principal in gestalt theory that a figure is perceived through its distinction from its background. I am layering several images from a single shoot, partially erasing and layering figures, blurring the boundary between what is figure and what is background.

Tags: Bill Durgin, Fresh2015, Interview, Klompching Gallery, Photography, Studio Fantasy

Posted in Photography | No Comments »