We recently sat down to talk with Kristan Kennedy about washing and wringing and allowing studio bits to get stuck to her paintings, sticking fingers into clay, and Miley Cyrus.

–Julie Dickover

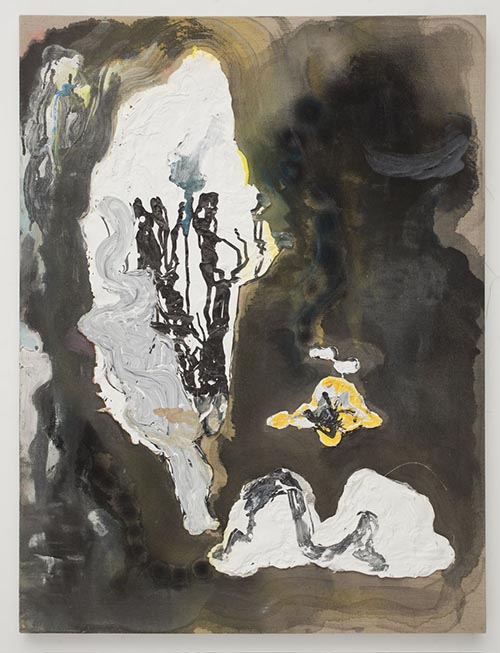

S.F.T.T.M.E., 2014, sumi, dye on linen, 75 x 51 inches

At Length:

The work you’ve made has changed quite a bit from the work you were making in the 1990s. While there is certainly a clear lineage, the older work was very illustrative, with abstraction relegated to the background. You mentioned to me that those illustrative elements were your attempt to lend meaning to the push/pull of the medium found in the background, but now you’ve made the background the new foreground. Could you talk about why you felt the abstraction couldn’t stand on its own?

Kristan Kennedy:

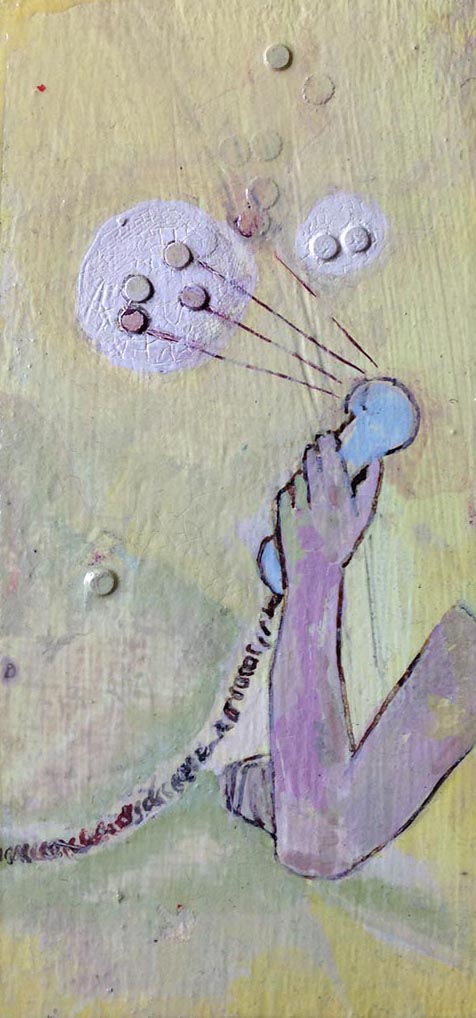

I think my older work was stalling or running in place a little bit. When I look at it I only see the insecurity and struggle that comes from trying to communicate meaning. In a sort of “post-collegiate” haze I was very concerned with them being “about” something. I felt it was necessary to plunk a delicate drawing on top of a very belabored surface. In this case, drawing little objects or scenes, or nods to landscape or other forms became a way to legitimize the work. In the end representation became a distraction.

To Take, ca. 1999, oil on panel

ca. 2011

As the work evolved, I started to imagine covering up those sweet drawings with amoeba like shapes, like throwing a drop cloth over a couch with an insipid cabbage rose print on it, not because you were about to paint the room, but because it was the most economical way to achieve blankness. You still knew the couch was under there — its shape told you everything you needed to know. I just started to trust my instincts and in the end it wasn’t that abstraction could stand on its own (we have the canon of art history for evidence of that) but that I could.

AL:

What occurred along the way that prompted you to embrace abstraction for what it was?

KK:

Along the way, I saw something in nothing.

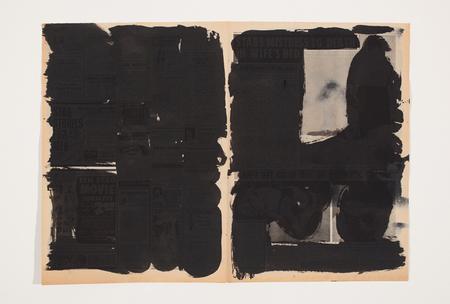

N.T.N.L.M.R.R.W.Y.T.B.L.R., 2011, Archival inkjet print, edition of 3

AL:

You used the word “cloying” to describe the work once you began to eliminate “information” from the paintings. Why ‘cloying’?

KK:

AHH! I think I meant less cloying. Less yes. Meaning, I could not escape a certain sentiment with representational work, an image of something inextricably linked to a feeling, time, place, or person — if not for me — for the viewer. It is why I started to upend my own work, by washing paintings out. Often when I return to a linen sheet, which has been wrung out by my hands or washing machine, the work I have done half disappears. I have collaborators in making them and they are chance and evaporation.

AL:

On that same thought, you also mentioned something about how presence creates an absence in your painting, and how this creates the potential for more meaning. Is this a characteristic you seek out when looking at work by other artists?

T.U.R.E.N., 2011, Ink and gesso on linen, 30 x 24 inches

KK:

No, it is not. I am glad there is not one way to make work or one resulting style. For now there is only one way for me.

AL:

I like that answer. Here are a few snippets from a text you sent me several weeks ago: “…Eradicating the hand while simultaneously respecting it…putting something in the painting, and then allowing for information to get stuck to it…information to be eradicated and destroyed (by the washing machine, by wringing it out, by covering it up, by bundling or tearing, by freeing it from the frame, by allowing it to fill or cover a room)…” I really respond to this, and the idea of creating a void in the painting, removing the hand while still respecting it, is very interesting. It’s a conundrum. If you are trying to eliminate information to arrive at a greater potential for meaning, what is the purpose of simultaneously allowing bits and bobs to get in there, incorporating found objects, etc.?

T.H.O.M., 2012, sumi and acrylic ink on linen, 25 x 24 inches

KK:

Those bits and bobs are just shapes, and they might seem additive but they obscure information too. In past paintings those adhesions were mostly made of detritus from the studio, bits of gesso pulled out of old dried up buckets or other abused art materials. So the stuff of the painting was made of the stuff of painting — exclusively.

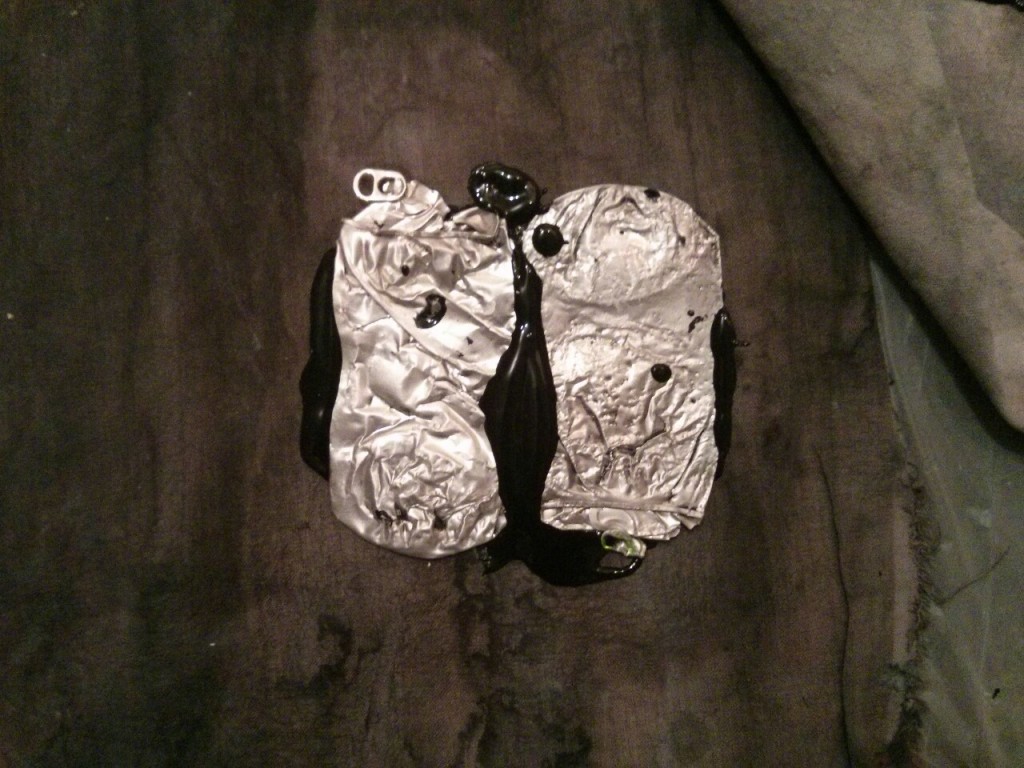

A.M.W.H.N.U.W.H.R.O.N.D.A.C.R.B.N.I.W.S.N.D.A.G.U.T.R., 2013, aluminum cans, gesso, sumi ink, acrylic ink and fabric dye, 178 x 79 inches, Courtesy of the artist and Fourteen30 Contemporary, Portland, OR

The flattened cans are similar in that they have gone through some kind of mashing or changing or mottling, and transformed into something new. They also were objects that were passed in between my friends for some reason, maybe in an effort to say “look at this nothing, isn’t it something?!” I was given a few that were so achingly beautiful that they just made their way into the paintings despite my own rules.

A.M.W.H.N.U.W.H.R.O.N.D.A.C.R.B.N.I.W.S.N.D.A.G.U.T.R., 2013, detail

AL:

What rules are those?

KK:

In this instance, the rules are to use what I have — gesso as glue to stick stuff to paintings that are also of paintings — so the cans deviate from this, as do the food tins I have recently been collecting. It’s all garbage in the end I suppose, and then it became silly to extricate anything from the paintings, so the outside objects found their way in. Otherwise, use my hands more than brushes. The washing machine and the sink and my buckets of water have equal say in what ends up on the linen.

Artist’s studio, 2012

Artist’s studio, 2013

AL:

You seem to embrace the utilitarian qualities of the un-stretched canvas, laying it over furniture, twisting it up on the wall like a curtain, draping it over some stairs. What does this mean for you?

Installation view, NADA Hudson, 2012, Hudson, NY

KK:

It’s about freedom.

AL:

Is this related to your self-imposed system of rules that you mentioned above?

KK:

Yes, possibly. Or maybe it is about freeing myself from the self-imposed rules of “the system,” and by that I mean my own impressions of what makes art legitimate. I am certainly not the first person to liberate linen from a frame and in fact I do make stretched paintings but for me it was about them having some potential for movement and shape shifting.

AL:

Is there a perfect environment in which you would like to see your work “installed?” I use quotes because as I write this question, I’m thinking of the image of the painting in the sink. So beautifully in its proper place in the world…right where it belongs.

Artist’s studio, 2013

KK:

Oh the sink! That sink is a piece of work in and of itself, a strange clunker that I love. I do like finding the right shape for a piece in the place it will live. The small blue piece that was in the show at Misako & Rosen was meant for a wall — it is a little scrap of a thing — but when Rob Halverson the curator of that show asked me where I would like it, I could not stop thinking of it sliding down one of their concrete stairs. And that is where it lived, or where it came alive.

R.B.E.S., 2012, Installation view, gesso, sumi ink and acrylic on linen, OO, Misako & Rosen, Tokyo, Curated by Rob Halverson

So is there one perfect place? No I don’t think so, although only one person has bought one of the un-stretched paintings at this moment. I don’t mention that to garnish more sales. It is curious that only one person could figure out how to live with it. The paintings seem to do best in the crisp white spaces of galleries. If I had my wish it would be that they would start invading domestic spaces; that they could live amongst the clutter from which they came. Maybe they don’t belong anywhere. I don’t know if I have a good answer for this one.

AL:

All of your works have interesting titles. Do those come to you quickly or do you spend a lot of time choosing a title?

KK:

My titles come from the same obfuscation techniques I use in making a painting. They are combinations of letters that I see on a sign, they are sentences that can be sounded out, they are things people say; they are nonsense and code. The Duchampian device of using only initials helps me not add another layer of words on top of a work. I tend to hold onto words for a long time and what I like about the titles is that I often forget what the letters represent. Forgetting is freedom too.

J.O.A.R., 2012, sumi and acrylic ink on linen, 31 x 22 inches

AL:

Do you ever forget and then wonder what mark you made on the canvas that you covered up with a crushed up soda can? That would sort of put you in the same position as a viewer looking at your piece for the first time…

KK:

I do forget. I want to forget. But there are prompts to remember, like the reverse side of the paintings often show traces and of course with looking comes answers. I am often in the position of the viewer, in a way. I can’t really see a painting until it is under the “good” lights of the gallery. My studio is a cave. So I am often surprised by my first read of a painting and the consequent reveals.

AL:

Are you still making small sculptures? How do you see these in connection with your painting?

KK:

Yes, but I am confused by them. I call them ‘punctuations’ — they are little weights that can go on the edges of paintings to hold them down. It is hard for me to call them sculptures although sometimes I use that word because it is just an easier translation for people. But I have so much respect for sculpture that it is hard to imagine these little paper clay turds being anything that grand! Still they take up space in a room a really tiny space.

K, 2013, clay, enamel, 3 x 8 x 3 inches

Right now they are just about jamming my fingers into a single block of clay and letting it be. I am partial to making the same ones over and over again, especially the one that leaves evidence of me gripping it with both hands. That feels like a physicalizing of my favorite painting method. Maybe they are close to the instinct of a mother to cast her baby’s first shoes in brass, or something like that.

AL:

I really like them and I think “punctuation” is a perfect description. At what point did you start making them?

Artist’s studio, April 2014

KK:

I started making them in 2006! But the only other time I displayed them was under a pseudonym.

AL:

You are also a curator at the Portland Institute of Contemporary Art (PICA) and an educator. How do these roles inform your own work?

KK:

It’s all work. It all goes into the same brain and comes out the same hands. I will say that when I started teaching a few years ago, I really needed it. It was revelatory to be with the M.F.A. students and have to figure out how to describe what I think the “now” is; how to track it, how to define it and how to ask questions about what history is. It was terrifying and incredibly rewarding.

My job at PICA has been the result of a slow evolution. My first act was to protest the institution, the second was to volunteer for them, my third was to exhibit there with my then collaborator and good friend Topher Sinkinson, my fourth was to join the board, my fifth was to join the staff, and my last transition was to start programming and nurturing artist’s projects and exhibitions. I had to call myself a curator because that is how I would get people to reply to my emails. Now I call myself a curator because I have lived the job for so long that it is a part of my identity. I only have one title for myself, which is artist.

W.R.D.R.M.R.N.G., 2013, dye, ink, aluminum, steel, gesso on canvas, 85 x 42 inches

I am an artist when I pontificate in the classroom and when I care for the projects and artists that I produce at PICA. I am an artist in and out of the studio.

When I was five years old and I was painting next to my mom I think she must have told me what we were making was “art,” and that we were artists. I fell in love with that word then and there, and like I said I hold onto words for a long time.

The other titles are for other people to be comfortable with in categorizing the different roles they think I have. What an artist is is not clear to me, I just know that it is the title I feel most comfortable with.

T.R.N.T., 2014, sumi, dye, gesso, aluminum, enamel on linen, Courtesy of the artist and Soloway, Brooklyn, NY

AL:

Do you know you have a Wikipedia page?

KK:

I just found that out and I have to say I am quite honored. I love Wikipedia; I think it is one of the greatest things ever created. I loved encyclopedias as a kid. The entry was written by Lisa Radon, an artist from Portland whom along with Julie Perini, Krystal South and others organized an Art+Feminisim Wikipedia Edit-a-thon to coincide with a national effort that originated out of Eyebeam in New York. Lisa approached me to fact check some things a few months ago and I was totally taken by surprise. It is so funny you are asking about it.

AL:

I’m curious if and how you feel living in Portland for so long has influenced your work in any sort of tangible or intangible way. I haven’t lived in Portland since 2000, but being familiar with the ways that Portland has changed since then, your work seems to have changed right along with it.

KK:

Yes, I think Portland has “influenced” my work in that if Portland were a person it would be a very patient low-key kind of person who encouraged you to be the most you could be. Living here has allowed me to gestate and not to feel pressured by trends or the market. The artist community here is incredibly supportive, collaborative and nurturing.

I don’t think it has influenced my work stylistically, but it has encouraged a certain slow evolution and growth for which I am glad.

Installation view, April 2014, Soloway, Brooklyn, NY

AL:

This was my first question to you when we began this conversation, but perhaps it is more appropriate to end with it. In your At Length Take This Quiz responses you included a video for Miley Cyrus’s “Wrecking Ball.” What are your thoughts on her? Does pop culture influence your work?

KK:

I was answering the question… “If scissors aren’t the answer, what’s a doll to do?” I selected the video because it has been on my mind — it got stuck in there, along with the song. It also felt like an exhibition or a translation of so many great things into one hyper cartoony freak-out, or the exhaustion of some “coming of age” story. It was about power and control and femininity and sexuality but in a messed up, convoluted, and potentially dangerous way.

Yet in the end when I read the question as a prompt, I thought to myself what is a doll to do? When scissors just won’t do, you then destroy things with your own hands, your image, people’s ideas about what is safe or sound, what is sacrosanct. I also picked a video of the C.O.B.R.A. painter Karel Appel freaking out on a canvas to his own composition. Together those two videos formed an answer for me and shared a certain pictorial energy.

For years I couldn’t even look at Cyrus, she made me physically uncomfortable, the twang of her voice and the careful staging of her life and career were not appealing to me. This is not because I have an aversion to pop culture or tween celebrities, but rather the awkwardness she displayed in her roles and the Disneyfication of childhood was repulsive to me. (I do understand however legions of fans loved her at this stage — but for me it just did not compute). I think with her album Bangerz came some radical transition in her image that looms like a surrender flag overhead. Not since Britney’s Blackout have I heard such a beautifully over produced pop album. The videos and her complicated over-sexed image are a whole other thing altogether, but I am also not as upset as others are about this. It is scary to me that it feels more “honest” than her wholesome country goofball persona, while it is so obviously a complete construction as well. I’m confused by it – and I like the tension in that. I just know that driving to California from Oregon with that album in my arsenal was a gift.

Does she or pop culture influence my work? Probably at some subconscious level. Art isn’t all about serious deep moments of exquisite composition (like any SWANS album); sometimes it is about a cheap, gross, guttural, unpopular, popular thrill.

*

Kristan Kennedy is an artist, curator and educator. She lives and works in Portland, Oregon where she is the Visual Art Curator at the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art, and is represented by Fourteen30 Contemporary Art. Her solo exhibition “Kristan Kennedy meets a clock” recently opened at Soloway (Brooklyn). Other exhibitions include “OO,” curated by Rob Halverson for Misako & Rosen (Tokyo); Kristan Kennedy & Gunta Stolzl, Zzzzzzz (New York); and Sleeper, Fourteen30 Contemporary (Portland).