interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

At Length: In your statement about the Kitchen Gods series, you said that a key kernel for the work was discovering a family photograph that had been damaged. Tell us more about that.

Priya Kambli: One of my most startling early childhood memories is of finding one of my father’s painstakingly composed family photographs, pierced by my mother. She cut holes in them, so as to completely obliterate her own face while not harming the image of my sister and myself beside her. Even as a child I was aware that this act was quite significant, but what it signified was beyond my ability to decipher. As an adult I continue to be disturbed by these artifacts, which not only encompass the photographer’s hand but also the subject’s fingerprints.

Even though her incisions have a violent quality to them, as an image-maker I am aesthetically drawn by the physical mark—its presence and its careful placement. These marred artifacts have formed a reference point and inspiration for my new body of work, Kitchen Gods, but they do not limit the form my own work takes.

The purpose and focus of this series is to create and contextualize a body of work that creatively references the conflict in the image-making process—my father constructing an image of his family through his camera lens and my mother re-shaping that image with her knife.

Muma, Sona and Me—from the family archive of Priya Kambli

Muma, Sona and Me—from the family archive of Priya Kambli

AL: You’ve gone on to create your own narratives, utilizing various techniques of manipulation. What relationship do these techniques have to the content of the photographs? For example: your use of rice and flower petals.

PK: My son, Kavi, once asked me if we were going to keep the flowers that I was buying at the grocery store, or if they were for art. The series, Kitchen Gods, is a conversation with my ancestors. The conversation begins with the family photographs that I carried with me in my suitcase when I moved from India to the United States, and which have been my companions ever since.

My choice of materials is dictated in part by play, and figuring out what works in the studio. My preference tends to be for materials that are domestic and humble in nature, and usually grounded in everyday use. But I think, besides being humble, simple, or common items, rice and petals (for example) are used to adorn household shrines—the kind of shrines Indian housewives keep in their kitchens. You might drape a garland of flowers over a holy man’s portrait, or a dish of rice might be kept, ready to use in small ceremonies (arthi). In my work I re-contextualize the familial qualities of these things, to serve my own artistic and creative purposes.

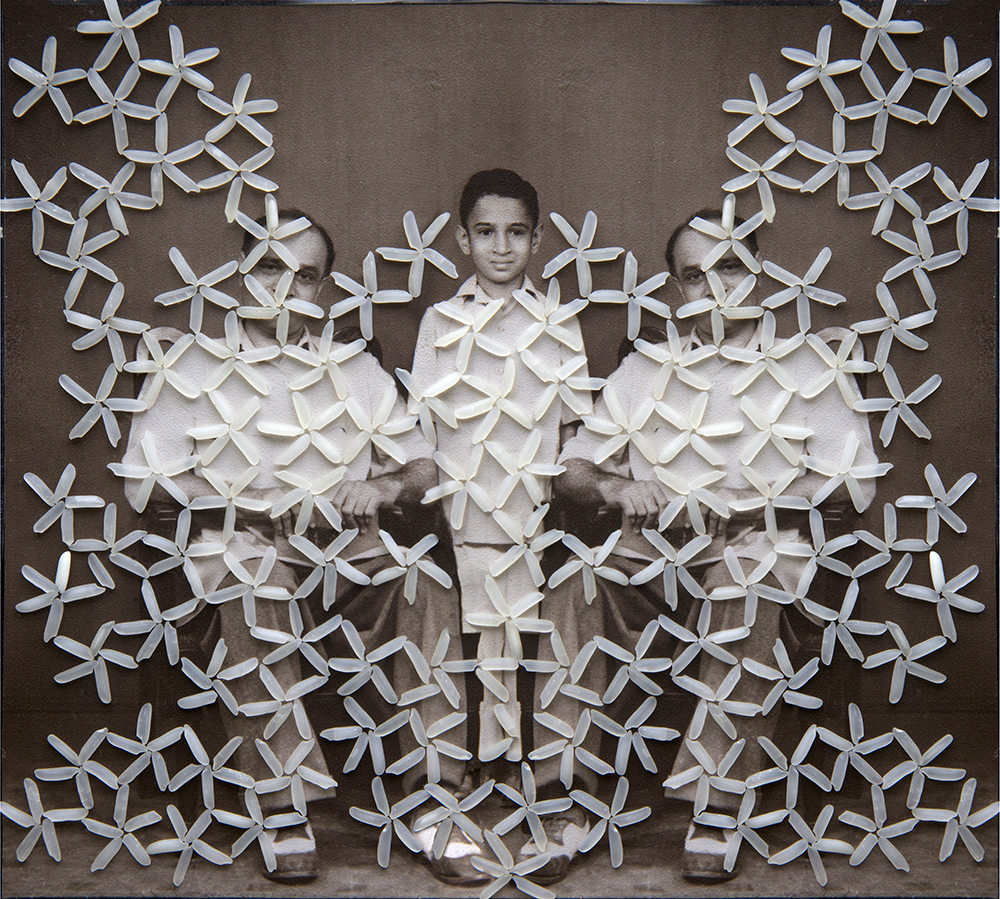

Mama and Dada Aajooba, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

Mama and Dada Aajooba, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

AL: And the intriguing technique of creating a partial mirror-image?

PK: Going through the family photographs I realized, because of the way my father photographed, there were a lot of duplicates–well, almost duplicates; the images had slight variations. I was really intrigued by this element of repetition and wanted to incorporate it into my own work.

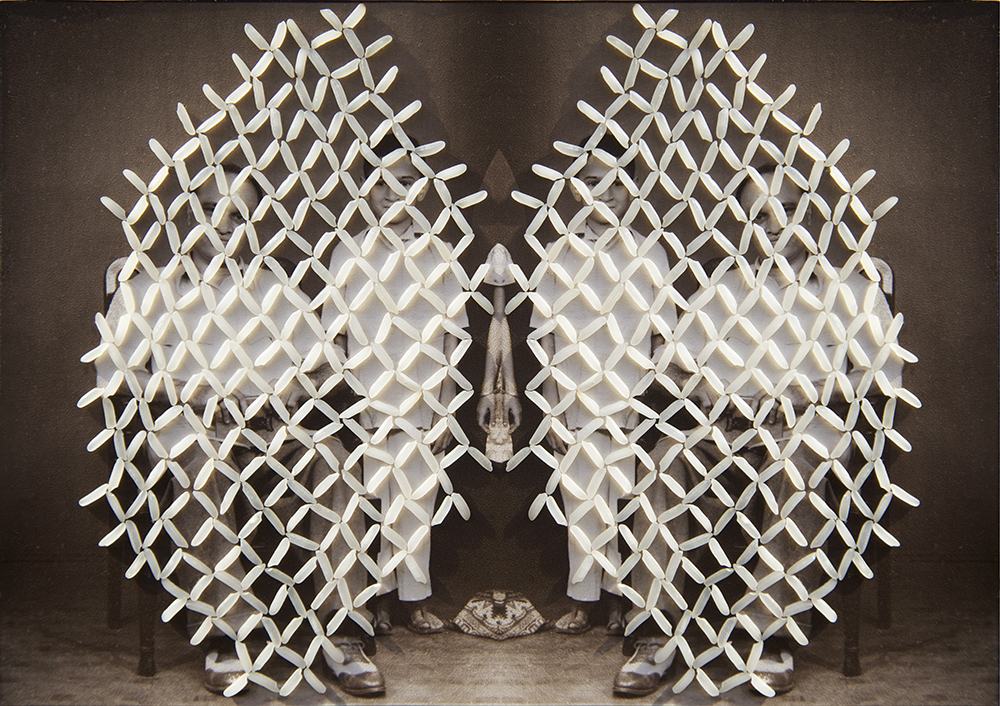

Dada Aajooba and Dadi Aaji, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

Dada Aajooba and Dadi Aaji, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

AL: There is the overarching theme of memory and family. What is your personal story regarding the meaning of these photographs? What does the title Kitchen Gods mean and how does this relate to the people in the images?

PK: My need to decipher and address my family photographs is personal. My work is rooted in my fascination with my parents, both of whom died when I was young. Therefore, for me these family photographs hold even more mythological weight. In my work I labor to maintain my parents and my ancestors, the way Indian housewives do their kitchen deities. I also strive to connect the generations—my ancestors and my children—who have been separated by death and migration. Like my mother, I alter these photographs to modify the stories they tell.

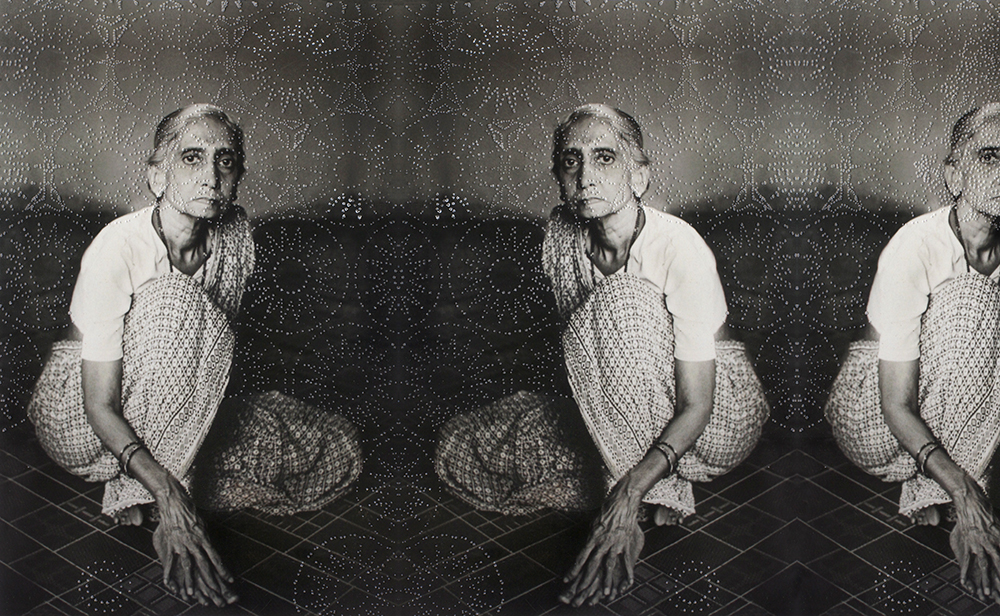

Aaji, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

Aaji, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

AL: The photographs are very intimate, and this is further grounded by their scale. Have you executed them in this way with the audience in mind or something else? And then, each photograph is presented with an expanse of white space surrounding the images. What is the purpose of this visual device?

PK: The scale of the image is derived from the original unaltered photographs themselves. Most of them are pocket sized, intimate, and now have my finger-prints pressed into them. I am gentle and rough when handling them, knowing full well that they are irreplaceable, but at the same time unable to refrain from playing with them—like paper dolls, cajoling them to come alive. The purpose of anchoring the images in the white space is an aesthetic as well as pragmatic selection, dictated by my choice of scale. I wanted to give the image prominence, without having to compromise on the choice of scale.

AL: Your photographs are clearly highly personal statements about family and the role of family photographs. In a wider context, what is the value of the family album to you? From the point of view of parent, artist and also academically—the family album as genre?

PK: I am fascinated by family albums, but I am also realistic and pragmatic about them. I am aware that for my children, disconnected from my roots, photographs of my family and ancestors don’t have the same pull that they do to me—their [my children’s] interest in these photographs and people is that of kind strangers. Through this work I am attempting to recreate a much more tangible family album that I can bequeath to them.

Dada Aajooba and Mama, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

Dada Aajooba and Mama, 2012–2013 © Priya Kambli

AL: What has inspired you to be a photographer?

PK: I never wanted to be a photographer. My most vivid childhood memories are of standing beside my sister in front of my father’s Minolta camera—waiting, while he carefully framed and exposed us onto film. My father, an amateur photographer, took the task of making images rather seriously. And we (my father’s family) often found ourselves to be his unwilling subjects. Our reluctance was related to his perfectionism. We, his subjects, were constantly herded from one spot to another, posed in one pool of light and then another. As a child I was certain that being photographed by my father was my punishment.

Interestingly I find myself donning the role of the photographer, demanding that same commitment that I balked at, hence most of my subject matter tends to be objects, artifacts or self-portraits—things that I can put through a wringer without feeling that I am donning my fathers shoes.

Priya Kambli was selected as one of the exhibiting artists for Klompching Gallery’s 2013 edition of FRESH: The Wall/The Page/The Internet, July 17–August 10, 2013.