photography by Beth Dow

interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

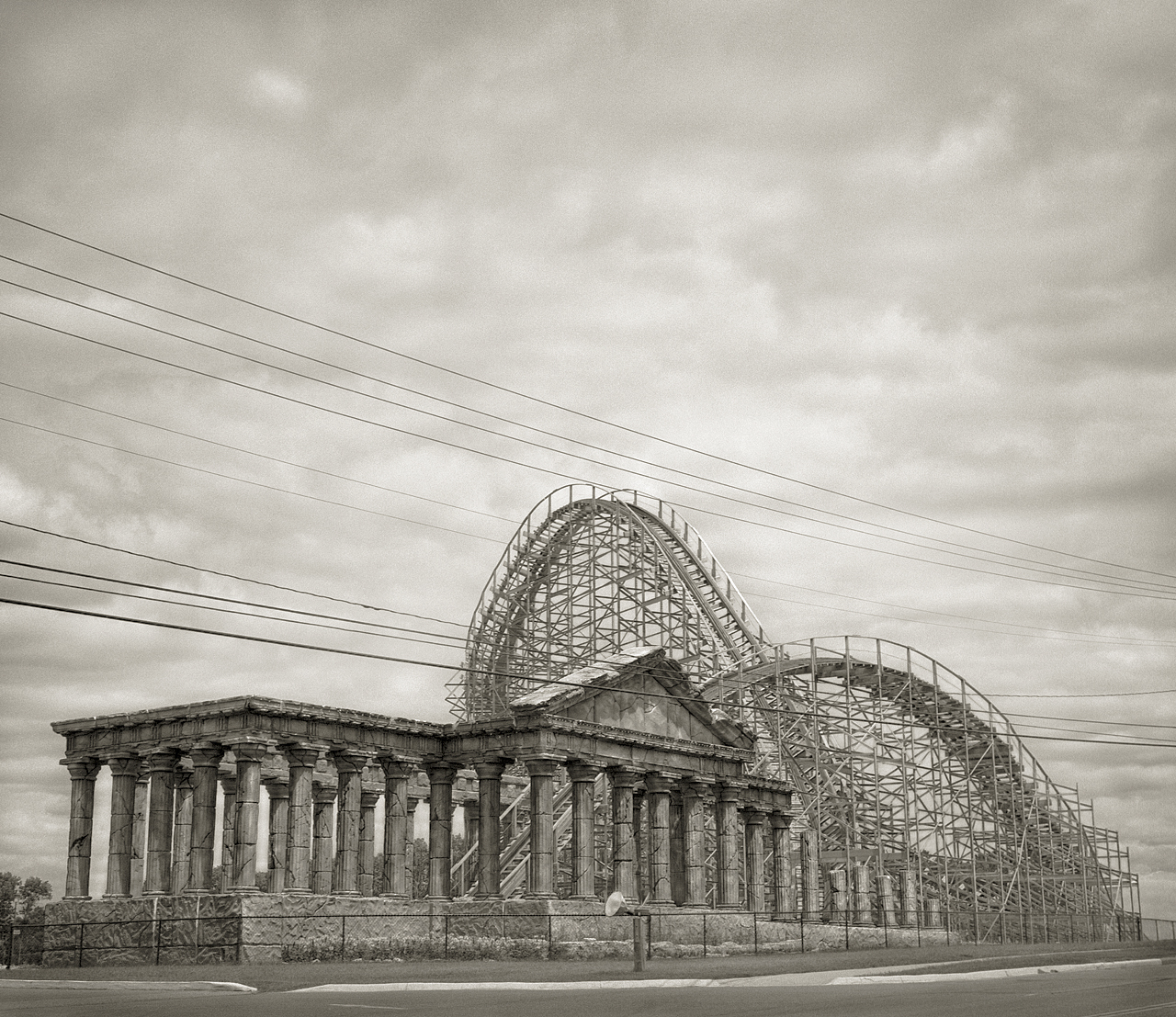

Coaster

At Length: How did Ruins come about?

Beth Dow: I was always fascinated by the work of Francis Frith and other expedition photographers, but Ruins began quite spontaneously. I was on a road trip working on a collaboration with my husband (the photographer and printmaker Keith Taylor) and we planned to reward our patient, long-suffering kids with some time at a water park at the Wisconsin Dells. It had just stopped raining one morning as we drove down the road, and the warm light was glowing on an odd structure that looked instantly like a Francis Frith photograph. It took my breath away, and I knew I had to postpone the original collaborative project. This first image became Coaster.

AL: There is a wonderment in seeing iconic architectural structures like the White House and the Roman Colosseum contextually displaced, framed within power lines and country roadways. Is this perhaps a statement on the decline of Western Civilization or a reverence to such structures?

BD: I know it’s easy to look at these follies with disdain, but I see something quite different. To me, they are signs that we have some sort of shared understanding that the past still has meaning. These are symbols we can recognize. The word “ruins” describes decay, yet I’m more interested in the ways these original antiquities persist despite their decay—they persist both in reality and in symbolic form.

The White House

AL: The majority of your work are Platinum Palladium prints. What is it about that photographic process that you feel is appropriate for your work?

BD: My earlier work was all gelatin silver, but I moved on to platinum-palladium several years ago because I wanted to work on nicer paper. I consider a photograph to be a complete 3-dimensional artifact, and platinum offers the best possibilities. A platinum print is constructed from the ground up, with home-brewed chemistry and hand-coated paper. Light burns an image on cotton paper infused with precious metals, and is so much more soul-satisfying for me than a spray of ink. I like all things mechanical, and it is a mechanical, analog process. I call myself analog-retentive.

Colosseum

AL: Keith Taylor is your printer, it’s a rather unique relationship in that he’s also your husband. How collaborative a process is it with you and Keith in printing your photographs?

BD: I used to work in gelatin silver exclusively, and printed my own work. I absolutely love printing, and would spend long hours in the darkroom. It’s one of my favorite things to do, and I’m rather good at it. Having said that, I have never printed in platinum, and am married to one of the very best printers in the world. Our process works quite smoothly. I scan my medium-format negatives, use Photoshop to burn, dodge, spot, and adjust contrast (everything I used to do in a darkroom) and then Keith prints a new, enlarged digital negative from that file before making a platinum print. My job is to give Keith a file that is exactly as I want the final print to look, and Keith’s job is to make that perfect print. He is so good at what he does and understands my eye and intent, so this is rarely a problem. Keith is also an amazing photographer, so he understands how important it is to the artist that everything is just right.

Trojan Horse

AL: Do you feel that there has been a recent revival of 19th century photographic processes?

BD: I don’t know if there has been an actual revival/increase of practitioners or a new willingness of curators and collectors to pay attention to the work. There is more than one way to make a photograph, but some people are too easily distracted by the bright and shiny. They sniff at any black and white work, but will go all fluttery in front of a photograph that is large and colorful. Regardless of the image content, one form was declared relevant at the expense of all others. I don’t understand that orthodoxy, just as I don’t understand the conviction of some that the use of a vintage process, regardless of image, automatically warrants respect. The digital age has us so accustomed to looking at images online, with our noses pressed up against glass screens, that the experience of dodging our reflection in the surface of an enormous Diasec-mounted print is familiar and reassuring. Handmade processes bring us back to the material nature of the medium, and remind us that photographs can be artifacts as well as images.

AL: Who or what are your influences?

BD: My Ruins pictures reference the work of photographers like Francis Frith, Felix Bonfils, and Giorgio Sommer, but also the ink drawings of Claud Lorrain and the etchings of Piranesi. My work as a whole is influenced by anyone willing to provoke, and anyone with a dark streak. I think I continue to make black and white landscapes partly because that very genre is so readily dismissed. My work as a whole is probably influenced by collages from the Dada movement, and I’m sure that is hard to believe. I relish the absurd, but especially when it is discreet. I shot a whole series in formal gardens, which sounds at first like a safe, perhaps romantic subject. However, I looked at those landscapes from a different perspective entirely, and on a more subtle and subversive level. Those pictures are filled with little signs of the natural world flicking us off. As much as people struggle to dominate and impose order over chaos, nature cheerfully undermines our efforts—I’m comfortable with disorder.

Aqueduct and Waterslide

AL: In Ruins, as well as in your previous projects Fieldwork and In the Garden, there seems to be a fascination with the human influence in shaping the natural environment?

BD: Always. I’m constantly amazed by our efforts to interfere with our environment. How do we do it, and why do we bother? Fieldwork came about because I love the curious forms that arise from our use of the land. They are not critical pictures—they are observations. I recognize that we use trees, which means we occasionally have to cut them down. I simply love the formal qualities of these alterations of the land, independent of any political or ecological issues, and look at them with only that in mind. I’m a very political person, but I choose to keep that out of my art. I aim to document my initial, pre-intellectual encounter with something. I work quickly with a hand-held camera, and look for things that I can’t quite figure out at first glance. This first glance is the most honest to me, because it is an event free of external influence. It is the only time I can see the world for what it really is, on its own terms. Our brains work furiously to make sense of the puzzling things we meet, but that rationality neutralizes and “humanizes” the experience. I try to capture the world, both natural and artificial, from its own perspective, which presents itself only in that quick and fleeting flash.

AL: Your projects often have a sense of nostalgia present. Where does that stem from in your work, are you a nostalgic person?

BD: I’m not nostalgic at all, which is why nostalgia fascinates me. I am interested in the processes of nostalgia and romanticism precisely because I don’t share them. I use vintage and contemporary methods while referencing the history of art—but this is all in the absence of nostalgia. I like the juxtaposition of disparate elements, much like standing on Earth, looking up at the night sky, knowing that the light from the stars is actually the distant past only just now reaching me. Someone out there in space at the same time wouldn’t see our reflected light until some point in the very distant future. Instead of nostalgia, I think I’m just willing to think of time as a plane rather than a line.

AL: What’s next for you?

BD: I recently went to Rome and am making some books from those new photographs. This is a sort of sister project of Ruins, and combines elements of authentic and fake antiquity in the form of handmade editions. I am also putting together a book of images that mess with ideas of space, time, and climate. When the weather warms up, I’ll continue my Ruins pictures, which I’m just so wrapped up in at the moment. I will also continue to expand Fieldwork, which can only be shot for a brief window of time each year. I would love to get a publisher interested in that project, and think it would make a fantastic book. I am always working on many things at once, but my biggest focus right now is on expanding Ruins.

To see more work by Minneapolis-based photographer Beth Dow, along with information regarding print sales and gallery representation, please visit her website. All images © Beth Dow.