interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

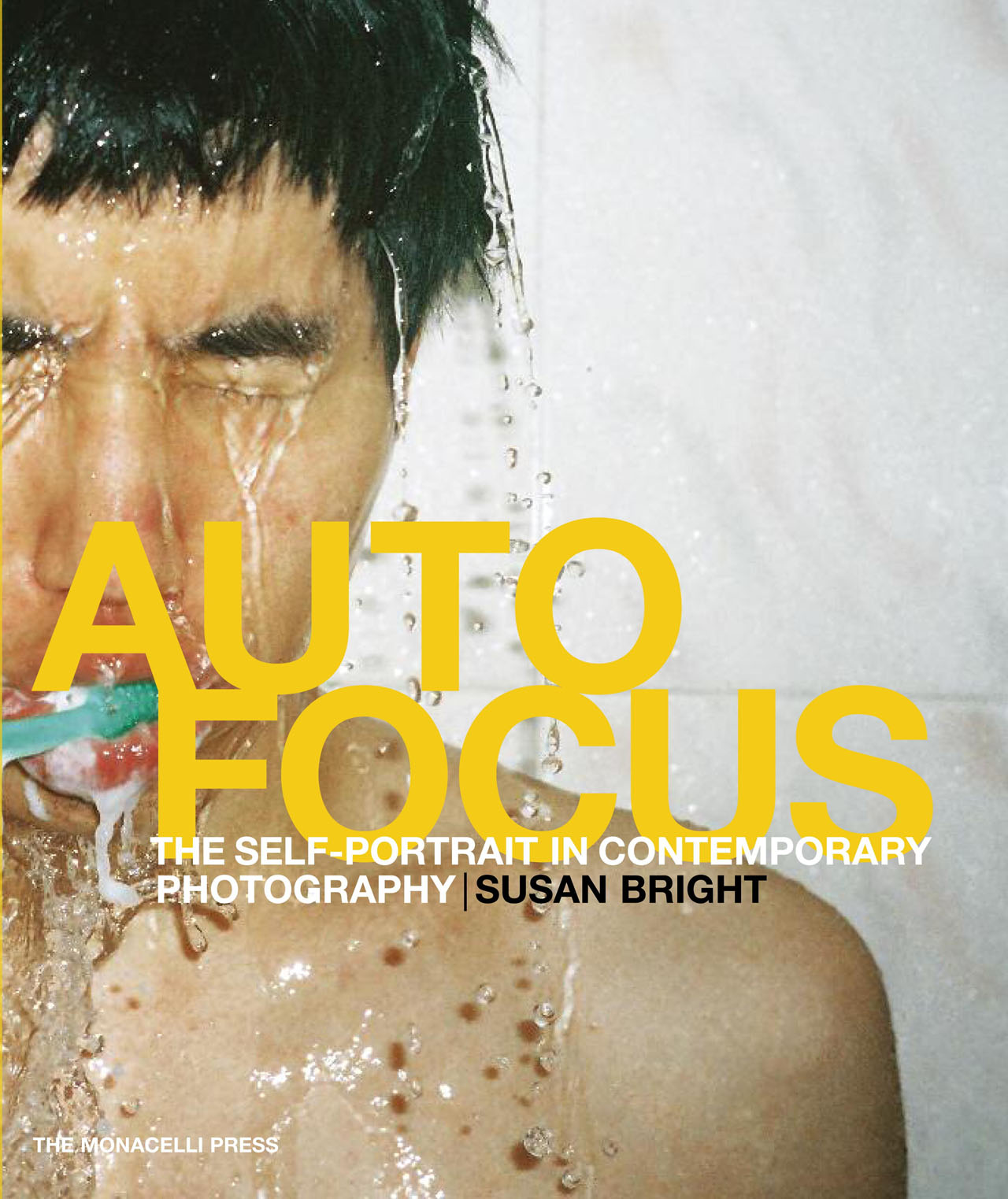

At Length: In the Introduction of Auto Focus: The Self Portrait in Contemporary Photography, you have charted a historical overview of photographic self-portraiture. You make connections to social/political contexts, as well as those of art movements more generally. How does this ‘setting the scene’ relate to the choices of images that appear in the book later on?

Susan Bright: Putting together a book is a rather weird and wonderful experience. You have to keep in mind your readers at all times. If I want to introduce some artists that might be challenging in some ways, then the groundwork and the history has to be laid out. I feel quite passionately about this. You, I and the readers of this interview are probably all quite sophisticated visual people, who are aware of the history of self-portraiture, but I want my books to be read by a wide audience, and that includes people who may not be. I want to be accessible. Also, when you are presenting contemporary work it has fascinating connections with older work and those are always worth highlighting.

AL: The book is broken up into five chapters—“Autobiography,” “Body,” “Masquerade,” “Studio & Album” and “Performance.” How did you determine which photographs slotted into which chapter, considering that by its very nature, self-portraiture crosses boundaries? Are you identifying these as areas of creative demarcation or are they more of a device for organizing the book into some form of logic?

SB: I was given complete free reign in how to structure the book and the chapters happened by looking at A LOT of work. I began to edit photographs into groups where I saw similar things happening or approaches that related to one another. Many of them are not a million miles away from what we have traditionally thought of as ‘typical’ self-portraits. I am thinking of the “Autobiography” chapter here, for example. However, I did want to show that autobiography does not just mean diaristic and that terms like memoir and fiction can play an important role in it. So, I guess in that respect I am updating how that specific type of portraiture is thought of.

What I found interesting was the amount of work made around the family album and in the studio. This is not surprising I guess—as the family album is in such a state of flux, so people are turning to it more than ever to examine their place in it before it disappears forever onto a Facebook (or similar) page. My parents always kept a family album but I don’t…. I guess many of the artists are grappling with that and are turning to their family albums as revered and nostalgic objects. The work made in the studio seemed to be a nice counterpoint to that.

I also wanted to highlight Performed Photography and not just Performance. There isn’t a huge amount written about Performed Photography, and British artists like Paul+A are doing really interesting things. They are not simply documentations of performances but something more intricate and interesting, where the act of taking a photograph during the performance is essential to the outcome.

So to answer your question, I guess the chapters were a way of organizing the book into some kind of logic, but they came about through creative demarcation.

Christian Thompson, Blackgum-2, 2007. Courtesy Christian Thompson and Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi, Melbourne, Australia.

AL: In the book, you feature “seventy-five of the world’s foremost contemporary photographers.” It’s refreshing to see that you haven’t selected the ‘usual suspects.’ How did you choose the photographers and what makes them the “world’s foremost”

SB: The “world’s foremost” is marketing speak! I didn’t write it. I would not describe the artists and photographers I have chosen like that, but do see the importance of doing so. Book publishing is a commercial business and it’s back to audiences. If somebody who is not familiar with art photography but was intrigued by the cover and the subject matter picked up the book and it didn’t have such a hyperbolic statement would they be less tempted to buy it? Probably.

Choosing the photographers was the most thrilling part of the process—and the most time consuming. From the start I absolutely did not want to make a book with the ‘usual suspects.’ I had seen a lot of work by photographers who were not well known and I wanted to include them as I genuinely felt they had something interesting to say. Whether they were famous or not was irrelevant to me. If the work was good it would make the cut. I also wanted to make the book as international as possible, so I put out calls to curators, editors, photographers, artists, gallerists and anyone I knew who worked in the creative industries around the world. I also contacted people I didn’t know to ask them if they could suggest people. It’s impossible to know what is happening everywhere in the world and I am so enormously grateful to those who got back to me and helped me. I learned a lot and became aware of many photographers that I didn’t know about before. From this initial gathering I edited and re-edited until it made sense as a book.

It’s worth mentioning here that the editing process for a book can be quite brutal and an artist can come to stand for a style. For example, in a book you don’t want too many artists working in a particular way as that would not make for at the most interesting book, so some photographers didn’t make it in because of the constrictions of making a book. That does not mean to say that I don’t think their work is good enough. Like I said… it’s brutal.

AL: Out of the seventy-five photographers you’ve profiled, who would you identify as being particularly important within fine art photography?

SB: Many of them are for very different reasons. The more established artists like Erwin Wurm, Nan Goldin, Martin Parr, Boris Mikhailov, Gillian Wearing and Joan Fontcuerta not only continue to make interesting work but are inspirational to younger photographers and artists and are therefore very important within fine art photography.

It was really interesting asking the photographers who they found inspiring and influential. The people they came up with varied enormously and included Elina Brotherus, Collier Schorr, Roni Horn, Sam Taylor-Wood, Duane Michaels. I found that perhaps two of the most well known self-portraitists—Cindy Sherman and John Coplans—were not mentioned so readily. I think their influence probably goes without saying.

Zhang Huan, Homeland. © Zhang Huan.

AL: What research methods did you use to find the photographers and how did they make the cut?

SB: I think I have answered this above, but to elaborate further. I would contact each photographer directly, introduce myself and tell them about the project. I would usually have a body of work in mind that I wanted to include but there were (many) times when I didn’t know all of their work or they might have new work they were working on and hadn’t been shown before. Through a series of emails we would come to agreement about what work would be included. It’s also worth mentioning here that this is a design lead book rather than a text lead book, so the designer (Anna Perotti, at Thames & Hudson) also had a say in the final edits as she was laying out the pages. She would send me page by page and I would comment. It was a very collaborative process and one I enjoyed enormously. Writing can be a pretty lonely existence so to work with others, hear their opinions, argue your side and just generally talk about photography with people is always good. I formed a great many friendships with the photographers in this book—more than any other project I have worked on. I think it was the subject matter—it allowed both of us to be very open with one another.

Perhaps this is a little oblique, but I think its worth mentioning. I did the majority of this book whilst I was either heavily pregnant or with a young baby. During this time my sense of self was hugely shifting (literally!), and the book became not only an intellectual exercise but one that was essential to me as a person. This is the first time this really has happened, and I made a decision that any large project I work on from now on has to resonate with me in a similar way. I was 100% invested researching and articulating issues of the self.

Patrick Tsai and Madi Ju, Untitled, ‘Tibet/Nepal,’ Nepal, 2006, from My Little Dead Dick. © Patrick Tsai and Madi Ju.

AL: We’re curious to know if you’ve seen any of the original photographs, or if your choice of images was based purely upon digital renderings? Do you think the method of viewing the photographs, within the context a book edit, is important?

SB: I am very old school and I prefer to see prints. I have just done a quick inventory through the book, and I experienced 4 photographers’ work through prints in the introduction (either through gallery visits, studio visits, museum and archive visits or having worked with them in exhibitions) and in the body of the book 30. Many of them I experienced through books and the rest on the web. Remember that a couple of photographers in the book (My Little Dead Dick and Jeff Harris) don’t have prints and their work is web based. It’s an interesting question and I see more and more on the web. There are some artists in the book where I have never seen their prints. That’s because they either live on the other side of the world or have not had a book published or not had an exhibition that I can easily get too. Everyone likes to moan about looking at photographs on the web, but I would never have been able to include many of the photographers I did without it. I think in some instances it’s crucial to see the print, but not always.

When I am writing an essay in a monograph for a photographer, I always ask for prints to borrow whilst I am writing. Some think I am mad. It’s expensive for them to print up and send a set. I do understand that, but I like to spend time with prints and edit them and have them to hand when I write. This is a luxury, I know, and one that is disappearing.

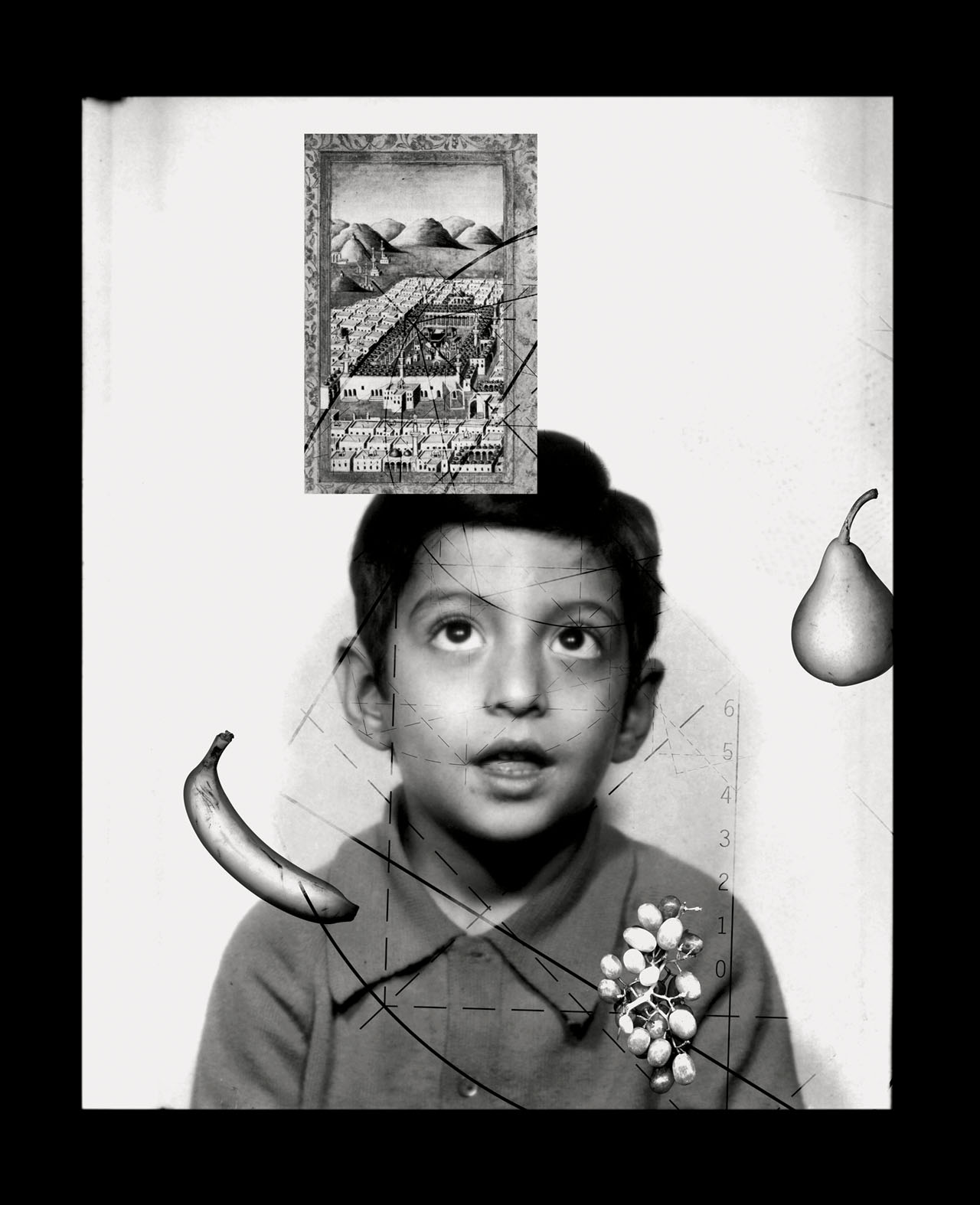

Anas Al-Shaikh, Memory of Memories 1, 2001. Courtesy Anas Al-Shaikh.

AL: We believe the book was a good five years in the making. Can you talk about this and how it impacted the final product?

SB: I was first approached to do this book shortly after Art Photography Now came out, so probably in the beginning of 2006. This coincided exactly with me being commissioned to curate Face of Fashion at the National Portrait Gallery (London) and co-curate How We Are: Photographing Britain with Val Williams at Tate Britain. It was impossible to work on all three projects simultaneously, so the book commission went on hold and I was officially commissioned at the end of 2007. As mentioned I then had a baby so it went on hold again whilst I was on maternity leave. So between these hiatuses I guess the time did add up. During the time I was working on the other projects it was sitting in the back of my brain and I was gathering images and articles as I came across them and storing them for use when the time came.

A book of this scale typically takes 2 years from being commissioned to publication. That is the publisher’s time scale and one I am very comfortable working within.

The time it took allowed me lots of time to think about it, which was great.

AL: There’s a lot of discussion right now about the state of curating, indeed, questions regarding just what curating is. You’re both a curator and a writer. Is there a difference between editing images for a book and curating for an exhibition? If so, what are the key differences? Are there any similarities?

SB: A book and an exhibition are completely different and the editing process has to change accordingly. They are so different it’s actually hard to compare. The worst exhibitions I have been to are books on walls. It just doesn’t work. When curating an exhibition, you have to deal with the physical space—you have a bigger variety of sizes and modes of presentation. It has to have more drama in it and theatricality. You have bodies to maneuver. It’s a bit like being a dj—you have to entertain, educate, get people moving etc.

A book, of course, does many of these things too but differently. The edits have to be more compact, often, and stand out on a page. I am finding it really hard to compare as my experiences with both are just so different. Editing a book (I don’t actually think books are curated) and curating an exhibition is a way of putting an idea forward, and each one has a different language and rhetoric.

Everyone is a curator these days aren’t they?! It’s a buzz word for editing anything; it both annoys me and amuses me. I guess everyone is a photographer and an editor too; terms become meaningless when they are overused.

Curating has changed so crucially from the original idea of the job (a caretaker of culture who looks after a collection and is engaged in scholarly research—something which is a primarily conservative endeavor) to something that does not necessarily need specialism, and the discipline is breaking down. Connoisseurship has been replaced by curiosity.

I think this mix is good and there is certainly room for both. I see myself as having a foot in each camp.

Kelli Connell, Around Here, 2006 . © Kelli Connell.

AL: Any predictions for future models of curating and/or image editing?

SB: Not really. Things evolve and fashions come in and out. I think people just do what they do and it’s wonderful when they do it well. Like I said, there is room for everything and it’s just a case of people finding what they are most comfortable with.

AL: Photo Book publishing is enjoying a renaissance—certainly with regard the monograph. This said, do you think there are ‘gaps’ to address through a survey book such as Auto Focus?

SB: I would like to see a survey book on contemporary Still Life, which I feel is going through lots of interesting changes and also a really good book on contemporary Documentary.

AL: If you could own one photograph featured in the book and hang it on your wall, which would it be?

SB: Serpent of the Nile by Hew Locke. I haven’t got the wall space though.

Nick Cave, Soundsuit, 2008. Courtesy Nick Cave and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

AL: What would your dream book project be?

SB: I have many. Ideas are not something I am short of! But what I would love to do is a really interesting book on 19th Century vernacular photography. When I was working on How We Are, Val Williams and I visited many archives that didn’t make it into the exhibition. I was blown away by the amount of 19th Century and early 20th Century work that isn’t really considered important or interesting in the canonized History of Photography. It’s such a wonderful period of photographic history and one which has been so misrepresented and sanitized in so many ways. It was exciting and weird and full of entrepreneurs and chancers. If time and money allowed I would really like to investigate the “shabbier” side of photography in the latter half of the 19th Century.

AL: You’ve previously authored several exhibition catalogues and the book Art Photography Now; with Auto Focus now published, what new publication and/or curatorial projects do have planned?

SB: I guess I am in the process of realizing another dream book (and exhibition) project. I am working on a curatorial PhD that will be both a book and an exhibition. The subject is contemporary representations of Motherhood in both fine art and the media. I’m at the beginning of it and there is much research to be done.

Susan Bright is a freelance curator and writer. She authored Art Photography Now and previous exhibitions and catalogs include Something out of Nothing, How We Are: Photographing Britain and Face of Fashion. She currently lives and works in New York and is a faculty member of the School of Visual Arts.