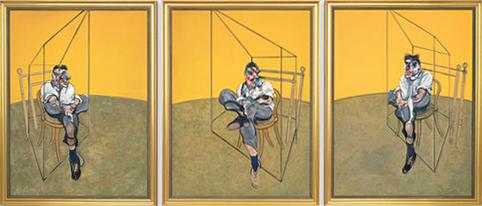

after Francis Bacon’s 1969 triptych of the man

“Great British painters, one might say,

imitate the proverbial behaviour of

buses. None come along for a century

or more, then two at the same time.”

-Martin Gayford

1.

Stendahl’s disease, I know, is bunk.

The spinning room and swoon, the paint—even Bacon’s, all carnival

grotesquerie—a psychic drain? In truth, our blood sugar’s low

from oohing straight through lunchtime.

And yet, I’m only steady at this bench.

I see Freud’s face travel like a triple stab; I see my love

(wet viscera, lamp glare, O.R.) meet our son—

and feel like one of Bacon’s hundred butchered

2.

portraits.

Lucian, Old Bean: it’s February on the South Park Blocks—

kids ride scoot bikes, the homeless sunlit—but you

melt indoors, a body poured

into wicker chair and headboard,

references, our curator claims,

to your fourteen (acknowledged) children. My son’s nearly four.

We’ve stopped to see the world’s priciest portrait.

3.

And we, like you, are also three:

my wife holds our son’s small hand; her free one finds, then slips

inside, my fingers— another under-the-kid’s-radar

communique that’s become our second nature:

He really needs to get outside she means

but leans in and whispers: Do you wanna keep looking?

I do, my love, I do

though your departure leaves me outnumbered

4.

and numb here, induced

by Lucian’s scoundrel charm— disarming still from these canvases’ hereafter.

Why does the repulsive draw me closer?

Enviable talent, absent parent, he made

sex and paint his life’s pursuits, eager

to seed his world with likeness.

Even now, bound in Bacon’s gaze, he’s fidgety and refracted— beguiling

as a volcanic plume encircling the planet.

5.

That planet turns indifferent to the years

it shears from our lifetimes. It turns, spurring us toward self-making.

We rake up whatever coals might glow

beyond our starless nightfall—

therefore children, therefore painting.

My son pauses beneath an exit sign; my wife glances

at a landscape. What will follow is an hour, love, parenthetical

inside our parenting. Kids are the afterlife that cost us all the others.

6.

Summer, 1982: Lucian, you’re dancing nude to Blondie’s “Sunday Girl.”

A lover knocks, a would-be model. You drink, you paint, you fuck—

until the cassette tape stops half-played, a moment unindulgent

Did you think to offer breakfast?

And what of the woman who flipped through canvases while you pissed,

who found someone else’s breasts, luminously hid?

Did she seek—like you, like me—maximum

fulfillment? Did she turn up Deborah Harry?

7.

A decade later: Kate Moss lets you paint her.

She’s often late “in the way that girls” are late (eighteen

minutes, you say), but still you’ll fill a canvas and tattoo her—

little birds where future lovers pass,

your needle flitting in and over skin while you share a taxi.

Did the portrait distill you more? More blood

within its bounds— more you below its surface?

Your child, Annie: your first full-length nude; your Bella got Moss to model.

8.

First daughter born in ’48, last son in ’84,

upwards of 30 (unacknowledged) more absorbed—like rain

on English country roads—into their mothers’ families.

Lucian, your lusts enamor me

but less than this question: how did you ignore

the tradeoff that plagues me: being an artist vs. becoming a parent?

I picture women, men—sunlit, kids in hand—walking

into a gallery. One looks unwittingly at her father.

9.

World where oughts like rural radio

exhaust, passing as one passes from their signal’s strobing ambit;

world of easements, world where meaning

slips free of some biologically

cold bond; world so New it flows—like you, Lucian—from the Old;

world where the gene pool is a canvas. “How shall we make love tonight?”

my new favorite character asks in the novel (my wife sleeps;

I read) about sex in a French village.

10.

Your answer: with arrogant abandon.

You double-dipped into the self you could endow, flecked

paint like a post-coital trail,

so beautiful, so boldly unrepentant.

Bacon was right to mangle you, though few today take notice.

I am the riverstone these visitors course round—

the CCTV cams won’t see me till they fast forward. A ghostly flow

divides us then— imagine your children are that blur; imagine them inattentive.

11.

Some nights we threw the covers down.

Some nights we sought

that lower ground where we dissolved coolly.

This was years ago, our child’s face a glaze we separately imagined

then worked to make through sex (no work) as you, Old Bean, had always

understood it: limbic, unprotected.

I stare into the faces Bacon lathed

and see the wound our love created—

12.

red of rare steak, gray like smudged lace—

the willful violence of a C-section.

My wife was there and she was not there.

I couldn’t look and then I had to: the scalpel’s soundless glint went in

to find our child writhing out from an incision.

And then a wail, two hands in air—

he grasps at fur we haven’t grown for ages.

A Moro reflex, the nurse confirms: our first fear is falling.

13.

A man will spend nine months imagining a son

until that son becomes a would-be poem: a name afloat, a nascent obligation.

He speaks to it but fails to see

that his addressee is just his echo.

I was goddamn Narcissus at the pond.

I am still someone who talks to paintings.

Did you, Lucian, give a thought to what your fucking

wrought? Did you grasp the casualties of imagination?

14.

And the surgeon put his staples in.

And my newborn squirmed, nuzzling my useless nipples.

I imagined

how he was our stone, a child who—for an hour now and hours

more—we’d carry in tandem. My wife nurses, I read; switch, repeat—

our sleep and light and limb indefinitely borrowed.

This painting, Lucian, returns me

to useless fantasy: there were years I lived, like you, unburdened.

15.

Insomnia, a summer: siblings ghost across our bedroom floor.

They mountaineer our shelves

and nudge books onto the carpet.

They commandeer the ceiling fan or build fires inside our boxsprings.

We’d stopped at one

and he knew why before the lies we told him.

“Will I have a brother soon?” he’d ask, and, before I could reply—

“Papa, when you die, I want to hear your songs on the radio.”

16.

My reply? (“Me too.”) All wrong.

I should have said:

“Love— most never have the chance to make them.”

Can you be haunted, Lucian, by kids you did not claim?

I’m haunted by those I have denied him.

Once you wrote: “The effects [that people] make on space,” will differ

as “a candle and a lightbulb.”

But what of the glow absence holds— our filament is cooling.

17.

I would, Old Bean—had I not (for years) asked art and books to pinch-hit

for God; were the consequences less certain—slash

your triple face and slip my head into each canvas.

But let’s be honest:

I am (white, well-off) leisured enough to lose an hour to paint;

I am (a dude) fixated on a wound I have no claim to.

So let me stand—

while half the city makes evening plans and half prepares to serve them.

18.

There’s a moment before you greet your child,

before they mark you as their own,

before they rise from all their little hands have done and run toward you—

before they’re yours, you’re theirs

and will be always.

There’s a moment before your spouse recognizes the footsteps as your own,

before she turns her head to break the fast that is parenting solo.

There’s a moment when your family is a photograph

19.

you could just walk away from.

My wife and son play hide and seek. He peeks out

from a pedestal—giggles give his place away—

and she pretends

she cannot see him. There is so much to write

about this scene— how pigeons shake the trees,

how an opera leaks from an upstairs window—

if I just had time to. A decade will fill with days like these

20.

and we’ll pay handsomely to live them.

And soon this game will end in tiredness or squeals, cheeks

smeared with applesauce, and napping

on a bus that strums a bridge that steelworkers willed over a river.

For now, though, I loiter here—

delaying the hours bound for bedtime’s diminuendo.

I claim a spot beyond their gaze, past the kiddo’s keener earshot—

I see you, loves. I see you.

NOTES

Geordie Greig’s Breakfast with Lucian: The Astounding Life and Outrageous Times of Britain’s Great Modern Painter (Farrar, Straus, Giroux 2013) was essential to the writing of this poem.

Additional sources include Martin Gayford’s Man with a Blue Scarf: On Sitting for a Portrait by Lucian Freud (Thames & Hudson, 2013); Robert Hughes’s Lucian Freud: Paintings (Thames and Hudson, 1989); and David Stabler’s article on “Three Studies of Lucian Freud” in The Oregonian (December 16, 2013).

“Three Studies of Lucian Freud” was on view at the Portland Art Museum from December 2013 to March 2014. It sold at Christie’s for $142.2 million. The buyer, initially anonymous, has since been identified as Elaine P. Wynn.

Derek Mong is the author of two collections from Saturnalia Books—Other Romes and The Identity Thief—as well as a chapbook, The Ego and the Empiricist (Two Sylvias Press). The Byron K. Trippet Assistant Professor of English at Wabash College, he writes about poetry for the Gettysburg Review and blogs occasionally at Kenyon Review Online. New poetry and essays can be found in Booth, Southern Poetry Review, Always Crashing, Free Verse, and The Hopwood Poets Revisited: Sixteen Major Award Winners. He and his wife, Anne O. Fisher, received the 2018 Cliff Becker Translation Award for The Joyous Science: Selected Poems of Maxim Amelin, now out from White Pine Press. They live in Indiana with their son.