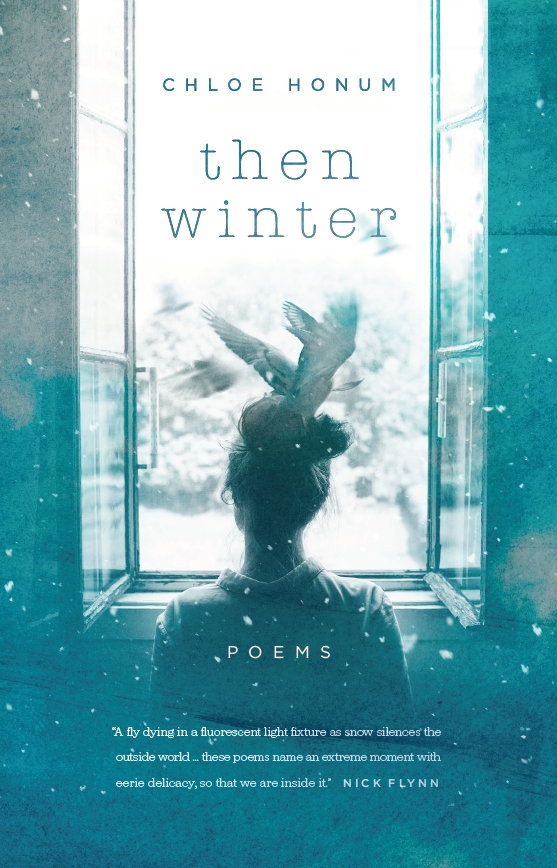

On Chloe Honum’s Then Winter

Lisa Russ Spaar

When asked “about poetry” by a fellow patient in the common room of the psychiatric ward that is the setting for many of the poems in Then Winter, the speaker in Chloe Honum’s “Rest” responds with a characteristic koan-like mix of clarity and mystery: “Flowers freshly cut and wrapped in newspaper, / that’s how I want to rest, my dreams / like white petals absorbing ink.” This trope captures the deceptively quiet, hibernal atmosphere and restive, primal, psychologically prescient imagination at work in Honum’s work. The flowers are wounded, “freshly cut,” and precarious in their swaddle of newsprint; like the ubiquitous snow falling outside and the fluorescent-lit rooms of the wards, the petals are “white,” but only appear passive, “at rest.” Instead, like an image in a dream, they are full of light and motion, “absorbing ink”; these petals make manifest the complex work of “translation” in Honum’s poems, in which—with astonishingly attentive empathy and perspicuity—she articulates the oneiric mesh of longing, dread, grief, and guarded hope that stalks her speaker’s psyche and characterizes the tenor of the psychiatric ward itself.

In “On the Stairs Outside the Psychiatric Ward,” the speaker and a couple of other out-patients watch in late afternoon as autumn “[throws] / gold and crimson leaves into the street / while starlings are holding tight on a telephone wire, / heads tucked in the cold.” With yearnings both private and collective, this trio gazes outward, “as though / we could solve that string of bird and sky arithmetic / and know the ages of our souls.” Going back inside in “Lunch Break at the Psychiatric Ward,” is, for the patients, like “venturing into the attics of our lives.” One of the psychiatrists “has a face like an old dictionary” (“The Ward Above”). A fly fallen from an overhead light fixture “buzzes and spins / on its back,” a helpless gesture with which the speaker, suffering love for what she has lost (a mother to suicide, a lover), closely identifies:

It resembles

A word scribbled out.

Won’t do, won’t do.

But oh you of the river-

wet lips, I miss you

this moment, and this.

Honum’s deeply intuitive, physical images are far from mere prop or adornment; they comprise, in an almost paraliptic way, a means of knowing that is both immersed in and beyond the reach of words—talk therapy, poetry. In “Early Winter in the Psychiatric Ward,” for instance, rain falling outside a room where the patients are engaged in therapy, comes “to a feathery end” and nearby geese

heave upward.

Their wings open like old heavy books,

their stories veering into the wild.

We cannot always parse out our own stories, yet these beautiful, brave poems insist on a place for language in a broken world, as in the end of “Note Home”: “The light is fluorescent. Everything hums. It is so important to go on naming, even if all I said to you this winter was snow, snow, snow.”

Rest

First one psychiatrist is gone, pulled away

on a tide of fluorescent light.

Then the other is gone too,

to tend to matters in the ward above.

In the common room, we talk about side effects,

night sweats and low libidos,

and about miracle drugs. Like a light switch,

one patient says, and we look longingly

beyond the window, at the birds

draped like strings of black pearls

around the saffron-colored trees.

The patient who thinks we’re actors in a play

asks me questions about poetry.

Flowers freshly cut and wrapped in newspaper,

that’s how I want to rest, my dreams

like white petals absorbing ink.

[Originally appeared in Alaska Quarterly Review]

Late Afternoon in the Psychiatric Ward

The fluorescent light

goes off and the shadows

fall apart like a cardboard fort.

The invisible should be sturdier,

like that stormy summer

the rain came so heavy

the waterfall was just

a thicker column of sky.

Now a fly throws itself

down on the formica table

and buzzes and spins

on its back, quickening

the poison. It resembles

a word scribbled out.

Won’t do, won’t do.

But oh you of the river-

wet lips, I miss you

this moment, and this.

[Originally appeared in The Volta]

The Ward Above

I don’t need to look up to know that inside some of the fluorescent lights there are dead flies on their backs, their wings at crisp diagonals. The psychiatrist has a face like an old dictionary. I imagine myself in the ward above, for the more severe cases. I’m afraid I’ll float up and ask to be admitted. In the common room, the Vietnam vet says, No, you don’t want to go up there. Everything he says, he says again with his eyes. At home, my dog sleeps beside me. She groans as I slide my hand beneath her head. I speak to her. I carry her warm, happy skull through the night.

[Originally appeared in Copper Nickel]

Lunch Break at the Psychiatric Ward

The fluorescent light is covering me like a hood of silk. It smells of sweat and medicine. The fish tank in the hallway is a risk and a gesture. A box of wonder—we are trusted not to throw ourselves against it.

*

Once, when I was small, my mother lay on the carpet and asked me to walk barefoot up her back. I grew very light, hovering above myself, and made the journey. I had to balance my distance from her body. When she rolled over, my feet became birds in the golden leaves of her hair.

*

Outside, the boy with the twisted body is leaning on his cane and smoking a cigarette. The sky, the snow, and the smoke pass gray, white, and silver around in a circle. In an hour we will go back inside the building. We’ll climb the narrow stairs, as if venturing into the attics of our lives.

[originally appeared in Waxwing]

Editor’s note: We’re proud to collaborate with the Durham-based publishers Bull City Press and Backbone Press to feature work from their latest chapbooks, including Chloe Honum’s Then Winter, which is now available for purchase.

Chloe Honum was raised in Auckland, New Zealand. She is the author of The Tulip-Flame, selected by Tracy K. Smith for the Cleveland State University Poetry Center First Book Prize. The Tulip-Flame was named a finalist for the 2015 PEN Center USA Literary Award, and won the 2014 Foreword Book of the Year Award and a Texas Institute of Letters Award. Honum’s poems have appeared in The Southern Review, The Paris Review, Orion, and elsewhere, and she has received a Ruth Lilly Fellowship and a Pushcart Prize. She is an assistant professor of English at Baylor University.