NOTE: “Hart” is taken from Catananche, the latest novel by Sophia Andrukhovych, a well-known Ukrainian author who lives in the capital. It was described by one critic as if Yorgos Lantimos’s The Killing of a Sacred Deer took place in a neighborhood of Kyiv. Catananche is a small flower, also known as Cupid’s dart, used in love potions during the Middle Ages. Its name comes from Greek, meaning “compulsive action.” The story is set in a near future after the end of the current war, which, while rarely discussed, is always present as each character processes their trauma in different ways. This scene happens before the novel’s present day. The main character Lesia has arranged for her husband Oleksa to drive Zhanna, their eccentric elderly neighbor, to a cemetery outside the city.

Keep reading after “Hart” for an interview with translator Ali Kinsella.

Доріжками серед могил вони рухалися без поспіху.

— Цей дядько завжди давав мені горіхи і вишні, коли я була мала. А ця тітка мала очі різного кольору: одне каре, а друге блакитне. Вона жила через хату від моїх батьків. А ця спочатку жила з оцим, а потім — з оцим. Бачите, вони й тепер у рядок лежать, а вона посередині.

Розповідаючи, Жанна тихенько сміялась. Її голос звучав заспокійливо — так потріскує холодильник, коли його розморожуєш: ледь чутно подзенькують шматочки льоду.

Від сосон віяло прохолодою. Всипаний сухою хвоєю піщаний ґрунт м’яко провалювався під ногами, дбайливо охоплюючи стопи. Корені дерев виступали з-під землі, немов цікаві ковтнути денного світла, і знову ховались у темряві.

They were in no hurry as they walked the paths between the graves.

“This old man here always gave me walnuts and cherries when I was little. And this lady had different colored eyes: one brown and one blue. She lived one house away from my parents. Oh, and that woman first lived with that guy and then with that one. See how even now they’re lying in a row with her in the middle.”

Zhanna chuckled to herself as she talked. Her voice was calming. It tinkled like a refrigerator being defrosted: the barely audible ringing of pieces of ice.

A cool air came off the pines. The silty ground covered in dry needles gave softly beneath them, enveloping their feet in a subtle embrace. Tree roots poked out of the earth as if they wanted to swallow a little daylight before returning to hide in the darkness.

“When my son was little, we used to come here to the cemetery and then go to the woods for a picnic. He said he loved these trips more than his own birthday. He’d run ahead along the path, scoot across the fallen tree over the stream, climb up the hill, find our spot next to the big bird cherry, and lie down in the grass there in his short shorts to wait for the rest of us. I’d see flashes of his skinny white legs through the tree trunks as we got close. Watch him scratch his mosquito bites, lost in thought.”

Her gaze drifted over the crosses and headstones, grazed the flowers planted on the graves. But then the rhythm of her steps broke: Zhanna paused to stare. She quickened her step. Her neck stretched out, her eyes squinted. She blocked the sun with her hand to see better. Her equanimity was gone. Her face tensed with alarm, her cheeks on fire. Her neck was quaking and the tender parts of her arms just above the elbows swished side to side.

“What the—! What is this?” she shouted and took off running, tripping clumsily in the sand.

Oleksa cursed and picked up the pace. He still had Zhanna’s bag of gardening tools over his shoulder.

“What happened?” He finally caught up with her at a grave overgrown with tall, colorful flowers.

Zhanna was sitting on her heels, back to him, digging in the dirt. Oleksa could feel her fervor.

“What’s going on?” he repeated, now aware that Zhanna was digging plants up, roots and all, with her bare hands. She spread her fingers wide and thrust her hands into the earth, scraping her nails as deeply as she could. She grabbed onto the stem and flower heads, showing no mercy as she ripped them out and piled them on the ground in front of her.

“She planted these!” Zhanna spat out. “You can’t. This shouldn’t grow here! It can’t.”

Oleksa stood silently behind her, his head bowed. He couldn’t feel that his shirt was wet with sweat under his armpits and between his shoulder blades.

“What’s his wife good for anyway?” Zhanna turned to him. Her face and hands were scratched by plume and milk thistles. “She didn’t stop him, didn’t prevent him from going. And now she’s planted dwarf everlasting on his grave. Everlasting!” She barked at Oleksa, “Why are you just standing there? Get the shovel out of my bag and help me dig ’em up.”

Oleksa obeyed. The small shovel refused to listen to him. The ground was soft, but nests of fine, tangly roots held fast to its clumps and it was hard to break through, to tear this many-ply net.

“At least put on some gloves,” Oleksa asked her.

Zhanna only waved him off and smeared dirt and blood on her cheek. The mud filled in her wrinkles and made it look like Zhanna had the head of some whiskered animal painted on her face.

“Okay, that’s done,” she said eventually, calm again. “Now we’ll dig up some ferns in the forest and transplant them here. Let’s go.”

They poured the remains of their water onto each other’s hands and washed some of the dirt off. Zhanna scooped the plants they’d ripped up into her arms. Bright flowers floated down with a whisper around her, falling on the path in a diaphanous shower of petals.

Zhanna said they’d have to go a bit deeper into the forest. There was a place where the ferns grew especially lush and they needed to dig up the strong ones with the healthy rhizomes so they could take root in their new home.

At first, Oleksa followed her along the path, but he soon stopped being able to make her out. The earth was the sepia of ancient conifers. From far off it looked like it was painted in thick, chunky strokes. The ground rustled under their steps. Ants scurried, going about their business on countless anthills. Spindly flies buzzed, their coloring making them look like wasps.

“There used to be a stream here and a fallen tree for a bridge.” Zhanna pointed at a small depression and the decrepit remains of an old trunk. “The water dried up and the ferns are all gone,” she said to Oleksa, quickly moving forward.

They reached another part of the woods. First islands of alders and birch appeared among the pines and firs, then an impassable overgrowth of hazel. More sunshine reached these parts. Thin yet sturdy blades of grass were green under their feet. Zhanna pointed to some tidy hemispheres between the trunks: bilberries, see.

She paused to catch her breath next to one sprawling bush. She threw her head back, staring up into the carapace of leaves filled with the squawking of birds as if she were examining the architecture of a cathedral. She reached out her hand and gently brushed a black tassel: the minute berries slid right into her fingers. Her lips reached down hungrily for them.

“I think it’s time for us go to back,” Oleksa said, glancing at his phone.

He was dying of thirst. The dry heat, impregnated with the scents of the forest, the sun-dried branches, and stalks, filtered into his body with a thick sluggishness. He felt drunk, unstable. His ears were ringing.

“Sure.” Zhanna shot him a disapproving glance. “I get it. There will be no picnic.”

She abruptly moved on, disappearing behind a hackberry tree. Oleksa cursed and followed her. Zhanna’s white shirt flashed between the trunks up ahead, a mirage.

“There should be a large colony of ferns right up here,” she shouted, not bothering to turn her head toward him. “Let’s veer a bit to the left.”

Oleksa sighed. There were ferns everywhere. With every step, they passed broad, drooping feathers with furled ends. The springy dark green fans swayed in the layers of sun-warmed air.

“It’s a warning,” Zhanna touched her tennis shoe to a rusty plaque half drowned in pine needles and moss. The letters were washed away. Her eyes traced a white-and-red ribbon that snaked on the ground, disappearing among plants, logs, and rotten stumps only to surface again. “I forgot there was an old resort here,” she said, rushing down the path where bits of asphalt were still visible here and there, broken up by weeds. She stepped over the steel mesh of a toppled fence. Marsh marigolds were growing in the gaps between the wires.

The ground here was sodden and squished underfoot.

“Come on, let’s turn back.” Oleksa stopped, hoping that Zhanna would finally come to her senses. But she pretended not to hear him. She kept going, like she was sleepwalking.

A concrete pad emerged out from the trees along with some decaying benches. A structure with a caving-in fiber-cement roof, emerald green with lichen. The remains of a gazebo.

They headed past some overgrown gladioli toward the two-story buildings. The tree trunks here were dotted with red barbs like some sort of ritualistic decorations. The windows and doorways looked like toothless jaws. Here and there the iron railings of balconies and porches were preserved. The quiet hummed. A lizard vanished into a hole in the threshold.

The ground was strewn with clumps of colorless junk. Fabric, plastic bottles, and tin cans rotting away. Crates and boxes, empty chests.

“An old ammo chest,” Oleksa said, pointing.

A buckle was sticking out of a mud-covered helmet. Zhanna poked it with her toe.

They walked around the structure. All that remained of the benches were the crumbling concrete supports. Broken tiles could be seen between them. Dry grass poked through the cracks.

Zhanna began to break through the blighted hawthorn bushes. Every leaf had been touched by some disease: a rusty black hole burned through the middle of each one.

She moved toward the sound of feeble splashing. A branch snapped under her feet and the splashes got louder, more fitful. It was like a big bird was beating its wings on water. Or someone was making waves with an oar, stirring up a pike. Oleksa had given up trying to stop Zhanna. He followed her out to the pool, but he was slower to realize what was going on.

There was a rectangular pit the size of a queen-sized mattress. Tree branches hung over its sides, some still alive and dressed in green leaves. Blackened branches lay in heaps along the edges. Once-shiny ceramic tiles, now bleached to an unrecognizable shade and jagged in places, were covered in a layer of dirt and mildew.

Much later, Oleksa reflected on this pool’s purpose: there weren’t even any pipes running to it and Zhanna had said the camp hadn’t had running water—where would it come from in this forest? When the camp was still in operation, people brought in water by hand, in canisters from a nearby lake. But it had been closed for ages.

The pool had filled with rain and the groundwater that made the surrounding area so soupy. Oleksa’s shoes were soaked through; his pant legs were wet almost to the knee.

The water looked black and oily. It was thick with decaying leaves, needles, rotten tree bark, paper, and plastic lids. And it was stagnant. Rather, it would have been absolutely still and dead if not for the waves, the nervous splashes full of despair raised by a hart over and over, before going numb with fear and fatigue.

He was exhausted. He had obviously been stuck in the pit for a while, but there was no telling quite how long. Maybe he was injured. Maybe his leg was broken and that’s why he couldn’t jump out.

His wet, brown fur was matted. His back and flanks were covered in old pine needles and speckled with debris, moss, and leaves.

The beast was gargantuan: a full-grown male with sprawling antlers that were clogged with branches and sticks, further constraining his movements. His antlers were so dense and dazzling that it seemed like a large, lacy ball hung glowing above the animal’s head.

His muscular body almost completely filled the space of the pool. Ceasing his struggling and fighting to get out, the deer froze. Shivers ran along his skin. From time to time, a spasm would push a muscle up. His ragged nostrils fluttered faster, emitting harsh grunts and snorts.

Trying to jump out, the stag pushed off the side with his two front hooves, drove his head and chest forward, but the matter ended there. Something must have been pulling him back into the darkness of the sour pool.

Zhanna threw herself at the animal; Oleksa couldn’t stop her. The stag suddenly jerked and stepped back, turning his long head, his eyes wide with fear. He snorted even more loudly, squealed, and moaned, sticking out his agile tongue. Zhanna fell to her knees and bent over the pool, holding onto the nearest trunk with one hand and reaching for the beast with the other, touching one quivering, restless ear. With her fingers, she felt the hot, perspiring flesh and bulging veins. The stag whipped his head and thrust his antlers forward, jostling Zhanna. She almost fell into the water, but Oleksa grabbed her shoulder and pulled her back from the edge.

“What are you doing!” he shouted helplessly.

She turned to him, overwhelmed with despair.

“We have to get him out!”

Zhanna stood up, shoving Oleksa to the side, and ran toward the building.

“Here!” she shouted. “Get over here! Fast! I can’t do it by myself.”

She was tugging on what remained of a rotten railing on one of the porches, trying to rock it back and forth to break it off. Oleksa did it in one try. The dry boards cracked, baring long, toothy splinters where they broke.

He carried the railing to the pool, though fear was crawling down his spine and legs to his very feet.

The stag backed up, lowered his head, and stuck his antlers out. His muzzle dipped below the level of the water. He emitted short, hissing sounds that sprayed the stinking sludge everywhere.

Zhanna plunged the railing down to the bottom, resting it against the side of the pool at an angle. She adjusted it. She gestured to Oleksa that they needed to get far back and out of the stag’s way. From behind branches and brush, they watched him make a few attempts to climb out, jumping on the railing with his forelegs before sliding back. Finally, he stopped and grew quiet. Only his ears cut through the air; ripples moved across his skin.

“Something’s stopping him,” Zhanna, losing her patience, said through gritted teeth.

“Maybe his hind leg is broken,” Oleksa said, following behind her. “You won’t be able to help him.”

Zhanna was already taking off her clothes. She wrinkled her forehead, squeezed her lips tight, narrowed her eyes, and stared intently at the stag who was stomping in place, making waves in his liquid prison. Her fingers nimbly unbuttoned her shirt to the last and lowered her pants past her hips, freeing first her right leg, then her left.

“Don’t do it,” Oleksa said.

But Zhanna was already sitting on the edge, dangling her legs in the water.

“It’s like diving into shit.” She twisted up her face and jumped. The murky water reached her breasts. She waded over to the deer, trying to go slowly.

“Don’t be afraid, kiddo,” she whispered, holding her palms out in front of her. “I want to help you. I’m gonna get you out of this stinky pit. I want you to run and graze.”

She slowly turned to face Oleksa.

“I can’t even imagine what’s on the bottom here,” she told him, lips twisted in disgust.

The deer moved toward her combatively and bellowed. He jerked his head from side to side, threatening Zhanna with his antlers. She froze with her hands stretched out in front of her. The stag lowered his muzzle to the water again, then froze, too, watching her.

Zhanna whispered something. Oleksa could no longer make out her words. Nor did he notice that he was afraid of shifting his body, which was so tense it hurt. It was as though his body was connected to the bodies of the woman and the deer in the festering water a few meters away, and if he flinched, a rift would come between those two that couldn’t be traversed.

He didn’t see the moment the touch happened. He saw only that the fingers of Zhanna’s right hand were on the stag’s wet side. Her hand rose and fell with the animal’s heavy breathing. Her palm slowly closed and spread on the stiff, sticky fur.

Zhanna stroked the animal, but so slowly that the motion was impossible to observe. After some time, both of her hands lay on the deer’s spine, her forearms touching its sides. Then her left hand glided to its abdomen. Her fingers left tracks in the fur.

Zhanna petted the large body, stroked the heavy head, broad chest, picked through the short hair near his ears with her fingertips. She spoke something directly to his face, looked in his eyes, breathed air into his cold, black lips. She danced around him, not moving the bad water.

The stag closed its eyes and looked as if it were falling asleep. The whistling of his nostrils and mouth became more measured and uniform. It was like he was blowing on the dirty water of his prison stubbornly and with purpose.

Still touching the animal, Zhanna moved around it to the back. Lightly splashing the deer’s rump, she slid lower. The upper boundary of the brown-green slime rose up her body, covered her wide-strapped white bra, spreading over the folds of fat under her armpits, the liver spots on her wrinkled skin, the jiggly flesh of her arms, and her saggy chin.

Oleksa opened his mouth to shout, “What are you doing?” but he couldn’t. He watched defenseless as her tightly squeezed lips sank into the darkness. Her cheeks disappeared, nose, and closed eyes. Her gray hair bound up in a bun soaked up the dirty liquid, getting heavier, and burped the little oxygen bubbles that had been hidden between the strands.

The stag was suddenly ill at ease. He anxiously shifted his weight from hoof to hoof, sloshing the slime on all sides of the pool.

In one fluid motion, Zhanna burst through the surface, grabbed onto the side, and pulled herself up. Sludge ran down her belly and thighs. Her underwear had been dyed the color of a swamp.

She was breathing heavily, her head and chest bent forward, and coughing. Her drooping nipples brushed along her knees, smearing the mud. Oleksa watched her from across the pool, unsure if he should go over and help. The stag kept stomping and jerking. He attempted to turn around, leaning first to one side and then to the other, getting his antlers even more tangled in the branches. His mouth was hanging open, his tongue lolling over his darkened, sharp-angled lower teeth. His upper lip revealed toothless gums cleaved down the middle.

“I felt it,” Zhanna was finally able to say. “His hind legs are tangled in some kind of wire. He has deep cuts, some all the way to the bone. There’s something tied to the wire.”

“What kind of thing?” Oleksa asked, drawing nearer.

She hesitated.

“Something round, kinda like a big metal pine cone,” she eventually mumbled.

They both knew what kind of thing that was.

“We have to get out of here,” Oleksa said. “We can’t help him.”

“Are you crazy?” Zhanna punched him in the shoulder. She was giving off a pungent wave of animal, earth, and rot. The mud had gotten trapped in her wrinkles, in the hollows of her dull, sagging skin, in her pores. It coated each of her hairs in a dark-green film, making her look even older. “I won’t leave him here,” she shouted and again jumped in the mud.

Oleksa reached under her armpits and tried to pull her back. But Zhanna was strong, and she had the weight of her whole body pulling down. Oleksa’s hands slid off her wet, slimy skin. She pushed away from the side of the pool with her legs and backside, twisting out of Oleksa’s embrace like a slippery, agile eel.

They tried to keep their struggle quiet so as not to startle the stag further. But they were unable to preserve total silence and motionlessness: they cried out and moaned, snorted, kicked up the water, slapped parts of their bodies against the broken tiles of the pool. The stag trembled and jerked, moving as far away from them as possible. His eyes—terrified, bloodshot, and full of tears—remained fixed on them.

Oleksa slid into the mire after Zhanna. He held her by the wrist, wrenching her backward. He tried to immobilize her by wrapping his whole body around her, shackling her arms with his own legs.

But she pushed him away with a powerful blow and thus began a battle in the muck near the stag’s hind legs. Oleksa spat out a film of warm mold. He cleared his eyes and nostrils and froze, hesitating, just a step from the animal. He was trying to decide if he at least should run away since there was no way he was stopping her.

Again, she surfaced, gasping for air. The knot on top of her head had come undone and long, wet locks stuck to her face, neck, and chest. Zhanna raised her hands up: Oleksa saw that they were bleeding.

“Pruning shears!” she panted. “I’ve got pruning shears in my bag!” before again disappearing beneath the stag’s rump.

Oleksa pulled himself up onto the side and climbed out of the pool. He was trying to ignore the smell that had seeped into his body and clothes, the weight of the mud-soaked fabric. He left a trail of wet footprints; his clothes clung to his skin and slowed his movements.

It took him a second to find Zhanna’s bag: she had dropped it on the ground in some bushes when she saw the stag in the pool. Oleksa dumped all the contents out onto the moss and ran back with the pruning shears, jumping straight into the pool. Zhanna was just catching her breath again, resting her forehead on the stag’s hip. The deer stood still, letting her wrap her arms around its back.

Oleksa pushed Zhanna aside with his arm and crouched down, sliding along the stag’s rear legs. He felt for the thin wire that had wrapped itself around the animal’s limbs countless times. It was hard to work with stiff pruning shears in that thick mire. The stag’s frightened movements and stomping were getting in his way. Sticking his head out to breathe, Oleksa heard Zhanna whispering to him, calming him down.

He finally figured out how to squeeze the handles so the shears would cut through the wire. Things started moving, though Oleksa felt the skin on his fingers and palms blistering from the strain.

One of his cuts finally freed something heavy. Oleksa felt its elongated roundness and wrapped his right hand around it down below. He stood up straight, holding his find as far from his body as he could. His gaze met Zhanna’s.

“It’s a dud,” Zhanna said. “It would have gone off a long time ago.”

With an unnatural slowness—from fear, from the resistance of the mud, from exhaustion—Oleksa trudged toward the side of the pool. Zhanna took the pruning shears he held in his other hand and continued freeing the beast. The stag could already tell he was saved: he moved his feet deliberately and with purpose, helping Zhanna untangle the wire.

He took a broad step forward and realized there was nothing holding him back anymore.

Oleksa stopped at the edge, not daring to release the black object from his hand. He observed as the woman and the stag moved clumsily toward the other edge of the pool, parting the layers of soured water.

Zhanna put her hand on the hart’s neck.

Looking him deep in the eyes, she said, “You need to step on this,” and she took a step on the wooden railing that was slanting out of the water. For a moment the stag stood still, as if considering something. Then he placed his fore legs on the assembly, which bowed and swayed menacingly, tensed his whole body, and then pushed off with his newly free hind legs, making it out in a single leap.

Zhanna shouted out loud, overcome by joy. She clambered out of the pool after the animal and, arms spread wide, received its shower of black spray. Having shaken off, the stag walked forward and back. He breathed in heavily and moaned; shook his head and neck impatiently; flicked his ears.

He walked over to Zhanna and for a moment rested his massive, bulging side against her breasts, making them even flatter. Zhanna gently ran her hands along his croup. The beast’s spiky, wet fur tickled her belly, which was spilling over the elastic waistband of her underwear. The folds of her waist trembled like gelatin as they kept stretching out, then doubling over on each other. Her wide, flat rear, encased in dirty undies that gathered in the central crack, shone pale from under their film of dirt. The hart threw his heavy head upward, opened his jaws widely, and bellowed.

Oleksa was still standing in the muck, holding the grenade in his outstretched hand. From this angle, he could see the stag’s long, pale phallus, which stuck straight out, turgid, twitching rhythmically.

Completely dazed with pleasure, he understood nothing. Her body was heavy and hot inside and out. He was getting burned, but couldn’t get enough of the fire. He held her tightly by the thighs and ass, grabbed her wide back, pressed her big, soft belly into him. Her fleshy breasts trembled and rolled under his chest. Slick and stinking, their bodies stuck to each other with slaps and slurps. They became a greasy piece of ancient, wet clay.

The woman’s face was distorted by grimaces. She shot him a burning look, ready to tear him to pieces. She licked her mouth, swallowed her spit. The man bit her lip and chin until he could taste blood. She threw her arms wide, exposing the dark hollows of her sweaty armpits, streaked with black dirt. But she held him so tightly between her thighs it hurt. He felt the moist, rhythmic squeezing, the greedy throbbing. She was pulling him deeper and deeper into her, sucking him in with her burning womb. He was melting. He was moved to tears. The woman dug her nails into his skin and jerked violently under him. He went blind. He was sure he’d never be able to open his eyes again.

When he did open them, he saw their spent bodies lying on a thick, crumpled carpet of fern fronds. Mosquitoes swarmed above them. Their high-pitched buzzing filled the air. The last rays of the setting sun fell through the pine branches and leaves of bushes. The light was viscous and languid. Something snapped softly between the tree trunks. A bird squawked languorously. It was so beautiful.

* * *

Sophia Andrukhovych is an award-winning Ukrainian writer and translator and the author of seven books of prose. Her novel Felix Austria, soon available from Harvard URI Press, was recognized with the 2014 BBC Ukraine Book of the Year Award, the 2015 Kovaliv Fund Prize, and the Visegrad Eastern Partnership Literary Award in 2017. In 2023, Andrukhovych’s fifth novel, Amadoka, was awarded the Sholem Aleichem Prize and the Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter Prize. It is due out from Simon & Schuster next year. Her latest novel, Catananche, imagines life after the war. Her works have been translated into English, Polish, German, Czech, French, Hungarian, Serbian, and other languages.

Author photo credit: Vasylyna Zakrevska

Ali Kinsella has been translating from Ukrainian for thirteen years. With co-translator Dzvinia Orlowsky, she was a finalist for the 2022 Griffin Poetry Prize, a finalist for the 2025 PEN Award for Poetry in Translation, and granted a 2024 National Endowment for the Arts fellowship. Her translation of Taras Prokhasko’s novel, Anna’s Other Days, won the 2019 Kovaliv Fund Prize and was published by Harvard URI Press in Earth Gods. She co-edited Love in Defiance of Pain (Deep Vellum Publishing, 2022), an anthology of short fiction to support Ukrainians during the war. She is currently working on Oleksander Dovzhenko, Anna Gruver, Halyna Kruk, Kazymyr Malevych, Iryna Vilde, and Sofia Yablonska.

Translator photo credit: Steve Kaiser

* * *

Interview with translator Ali Kinsella

AF: Thank you, Ali Kinsella, for taking the time to let me (Anne O. Fisher) interview you about your work as a translator. I’m really happy that I get to publish your rendering of this excerpt from Sophia Andrukhovych’s novel Catananche as the inaugural At Length translation feature! As I read your piece, there was a moment where I got the image of the wrong kind of fence: I thought it was a chain-link fence, but it’s not, it’s another kind of metal wire fence. You explained this, adding, “For what it’s worth, I don’t necessarily think we have to convey all the realia of the history and setting, but I don’t want to add something that feels American to me.” This is such an important topic. How do you pick which realia to keep, and which to leave out? When might you decide to go ahead and do a cultural substitution or otherwise make something more familiar?

AK: In thinking about this, you got me to go back into the translation and change “wrought-iron railing” to just “iron railing” because I think “wrought-iron” introduces an element of luxury that is definitely absent in the original. But I’ve also found a place where I allowed myself a domestication that felt acceptable: “a rectangular pit the size of a queen-sized mattress.” Mattresses in Ukraine are sized differently, so I know that I added this. Let’s see, it was originally a “two-sleeper mattress.” To my ear, “two-sleeper” mattress is going to really stand out and distract the reader, shifting attention away from the size of the pit, even if I polish that translation a bit. And it’s just not important: the mattress isn’t there; this isn’t a treatise on post- Soviet sleeping surfaces (which would have to include multiple chapters on the sofa bed). The comparison is supposed to be so familiar that we immediately know how big that pit is. But the fence Zhanna steps over is actually there, and what would a chain-link fence be doing at an abandoned sanitorium in the woods? I think that for me is the difference. (I’m also questioning my decision to repeat “size” in that phrase, but I will defend it for now. For one, “queen-sized mattress” feels better to me than “double mattress.” I’ve also been trying to check my urge to never repeat words because I think it elevates things to a literary level beyond ordinary speech and I want to be literary without getting too far away from that.)

AF: Talk about the difference between stag, hart, deer, and buck. Were you already versed in the distinctions between European deer (red deer, brown deer) and North American deer (white-tail, which I think are smaller)? Or was this a lot of research on your part? Rendering animal and plant species across geography and across cultural connotations is always difficult!

AK: I don’t know that I’m all that versed in these differences now. I grew up in the woods in southern Illinois and we saw white-tailed deer all the time. I remember going on a road trip out west in college and seeing mule deer on a barren hill that had burned a year or two before. The landscape was sort of alien and the deer seemed so different from the ones I was used to seeing, stockier and shaggier. I don’t know if I even realized at the time that we had different species of deer in the US. Looking at pictures of the two now, I’m wondering if I’m not totally full of shit, because they don’t actually look all that different. But they did to me then! I also remember seeing roe deer when I lived in Ukraine. I had a very limited dictionary at the time and no access to the internet, so the best translation I could come up with for this species was “chamois deer,” which my friends and I thought was very funny.

When working on this piece, it was important to me that the magnificence of this animal come across. I went back and forth between “stag” and “hart” because I wanted to set this animal apart from the deer that would be most familiar to my American readers. At the time, I thought “stag” was a general word for any adult male deer (this is probably the fault of Stag Beer, which was originally brewed in my hometown and now enjoying a sort of populist renaissance). “Hart” to me seemed sort of European and fairy-tale like—never a word we would use to describe an animal we saw in our backyards. It seems I was mistaken, though, and “hart” and “stag” are both reserved for red deer alone, just at different stages of maturation. “Buck” wasn’t an option for me because that positioned the animal squarely in the realm of hunting and prey, at least to my mind.

But what was most important was convincing the reader that there could be an animal large enough to fill a (small) pool. That this animal could have so much power reserved in its body. Zhanna’s actions have to come across as courageous and crazy, and the size of the deer helps convey part of that.

AF: Your translation captures sensations so beautifully: there were moments that I tagged as gorgeous yet faintly foreboding; or the descriptions of the mesmerizing texture of wet, squishy, pliable, almost-liquid earth; or the amazing description of what you called “the muddy deer sex scene”; or the lovingly grotesque details of Zhanna’s body as it reverts to being more like the stag’s: dirtier, wetter, (more) naked. Was this sensuality or physicality part of what drew you to this piece? What did draw you to this piece?

AK: Oh, it was the shit-covered, intergenerational, body-positive sex scene. And also I like anything that foregrounds the experiences and perspectives of older women. I read the novel and liked it, but this was the scene that immediately jumped out to me as the one to translate in isolation. The rest of the book covers a lot of ground for being so slim (including being bookended by a foray into Greek mythology), but is more about relationships gone wrong (mother-daughter, owner-pet, husband-wife, neighbor-neighbor, teen-teen) and, in some ways, requires more context to get into, whereas this does such a good job of standing on its own.

All beautifully captured sensations are Sophia’s doing! She wrote it, after all. I’m not saying this to deflect, it’s just not my task to introduce beauty where it wasn’t already in the original. In this sense, a translator can only fail! There is successfully rendering the text in your target language, in which case the author is responsible. Or there is not, which is the translator’s fault. Okay, so now I am being a bit reductive. I did look for a lot of sound and feeling words and then try to put them in all the right places: soupy, sodden, matted, sludge, festering. This is maybe where I confess my preference for Anglo-Saxon words over French borrowings (though perhaps this list does not reflect that). I have this nonrational belief that these words affect native English speakers more.

AF: You have translated so much, and you also taught the Literary Prose translation seminar at the 2025 Translating Ukraine Summer Institute, or TUSI, in Poland this past July. So you have worked with a lot of different styles. What are some of the qualities of Andrukhovych’s style that are interesting or challenging to work with as a translator?

AK: I think that Andrukhovych has evolved a lot as a writer, or perhaps not “evolved” because I don’t want to suggest she is or should be headed in a particular direction. Andrukhovych has been writing for a couple decades now and she has amassed a diverse body of work. Some of her prose is exceedingly lyrical and evokes a feeling or a place without focusing as much on plot. I’m thinking specifically of her short story “An Out-of-Tune Piano, an Accordion,” (in Love in Defiance of Pain, trans. Vitaly Chernetsky). Her novel Amadoka is a sweeping tale—over 800 pages long, comes with two ribbon bookmarks, published as three volumes in German—of Ukrainian history that delves into the actual archives. Catananche, on the other hand, is quite short. It’s barely 200 small pages and it has no chapter breaks.

In March 2022, Andrukhovych said this in the London Review of Books: “Before the war, I was a writer. Today, on the ninth day, I feel unable to string two words together. . . . I don’t know if I’ll write again after the war” (trans. Uilleam Blacker, London Review of Books 44, no. 6 [March 24, 2022]). I recently translated another piece she wrote for Vogue UA that mixes descriptions of a beach vacation with details of sea slug life cycles and also talks about war. I thought it was very cool and in between genres, sort of like documentary fiction. I think it’s possible that the “slightly detached style with lots of shorter declarative, descriptive sentences” you picked up on are her way of “writing after Bucha.” This could mark a turning point in her prose. We’ll have to keep reading.

One thing we discussed at TUSI was ways to emphasize limiting or limitless impulses in a translation and the conditions that might call for one or the other. I personally find it sort of hard to make the switch back and forth and think that my voice as a translator is just better suited to certain authorial voices over others. I suspect that’s what’s going on here; I’m just a better match for post-2022 Andrukhovych than pre-2022.

AF: One self-study tool that is often recommended to literary translators is to find a text and translate a page of it, and then read a published translation of that same page. But you mentioned doing something during your TUSI seminar that I think is brilliant: reading translations into two different languages of a text originally in a third language. You read Antonia Lloyd-Jones’ English translation and Ostap Slyvynsky’s Ukrainian translation of Olga Tokarczuk’s The Empusium. You described this as a way to shift analysis away from “right” and “wrong” translation and instead focus on how different languages deal with the same challenges – especially with regard to modifiers. Can you talk more about that?

AK: Oh, I can talk about this for exactly three hours—you should have come to the seminar. This was an exercise that I had long wanted to do for myself, but it’s very hard for me to find time for things like this. As you know, translation is often undercompensated and when I am working, I usually need to be putting words on the page. But when I finally got around to this translation comparison, it was so much more rewarding than I’d ever imagined—I would have done it sooner if I’d had an inkling. I think it works as an exercise because it breaks down this notion of authority—neither text is responsible to the other. Sure, it helps to start with two translations that you know are good or were well received, but the “right” answer isn’t in the game. (I did actually make the Polish original available to students, but we mostly ignored it. When we did refer to it, we were usually surprised to find our assumptions were wrong.)

Translators into English from any language can easily do this exercise because you don’t actually need to be able to read the source text; you just have to find something that was translated into both your language and English. And it’s terribly liberating. So when you see that Ostap Slyvynsky has privileged a verbal construction and Antonia Lloyd-Jones conveyed the same idea without using a verb at all, you begin to think not about how one of them could have done it differently, “succeeded” in finding a syntax that would allow them to keep that part of speech, but why they each made the choices they did and how this information could inform the choices you yourself make. In doing this, I was able to come up with three categories of differences between Ukrainian and English: major structural differences that should always be at the forefront of my mind when translating; minor structural differences that I can refer to when I find myself stuck; and stylistic differences that are sort of just reminders to myself that these are places where I can have fun and really just make the choice that the translated text calls for, sort of without regard to the original.

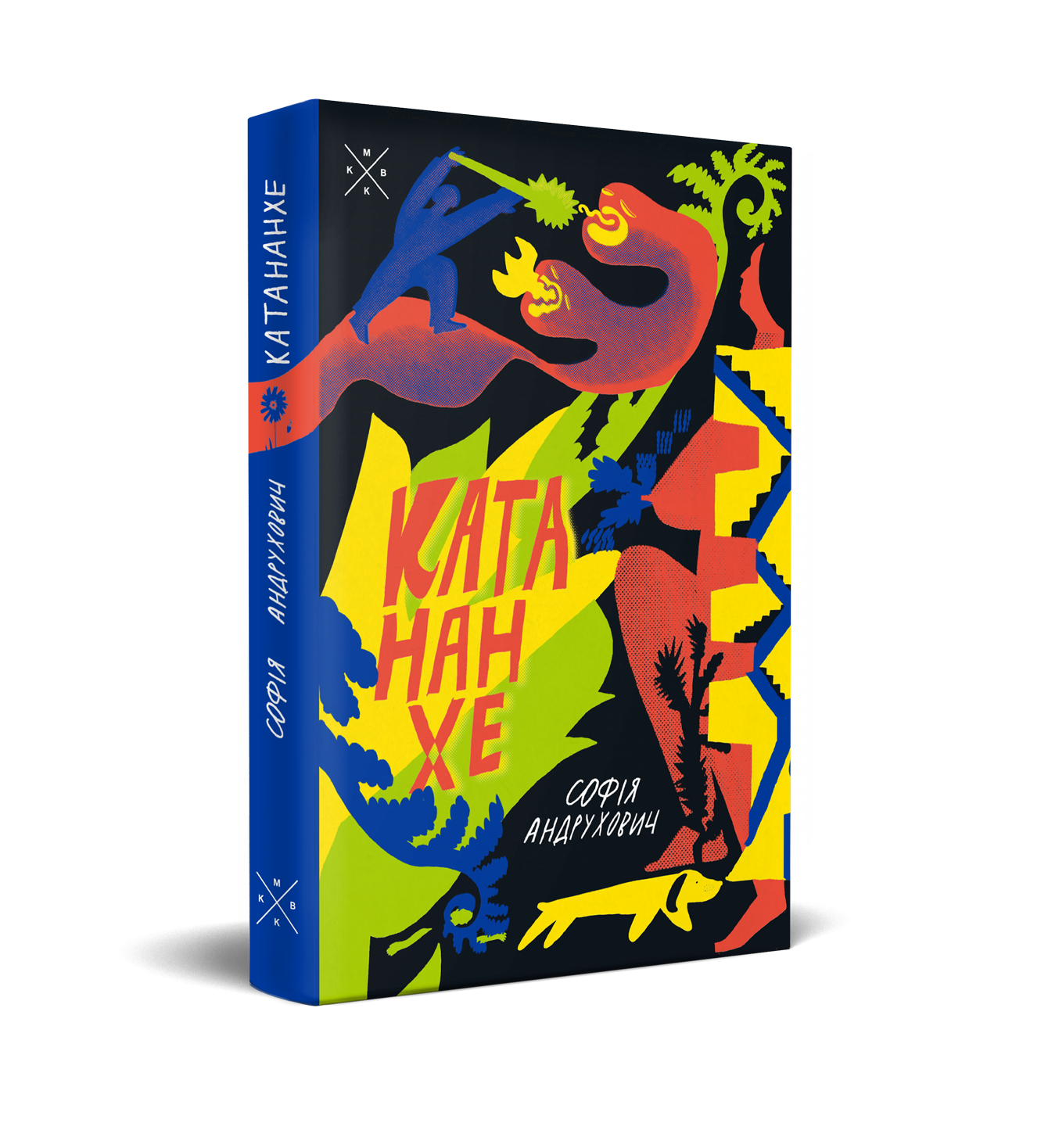

AF: For our next interview, I’ll ask you for a deep dive into those categories. That kind of detail talk is dessert for translators. One last question: the original Ukrainian book is striking not only because of its amazing cover art (which is the image accompanying your translation on At Length), but because of the nature of the publishing house. Can you describe what makes Komubook different from other Ukrainian publishers?

AK: As far as I know, Komubook is the first crowd-funded publishing house in Ukraine. They focus on translating heavy hitters from the West—Foucault, Wolfe, Said, weirdly all of Philip K. Dick—but also seem to have it as their mission to bring back forgotten Ukrainian hits. I’m purposely not saying “classics” because there is a parallel project happening all over Ukraine right now to rediscover the classics of the 20s, 30s, 40s, and so on, and there are a handful of publishers really actively pursuing this. But Komubook—which means “Who wants a book?”—is interested in cult favorites of the 90s and early 2000s. They’re getting ready to rerelease one of Andrukhovych’s earlier novels, but Catananche might be the only new novel they’ve published.

They clearly state on their site how much it costs to print each title—about $8000—and they ask readers to preorder their books. Once the project is funded, the book goes to press and people get their books on the back end. You can also sponsor books for libraries. Their next wave of projects includes Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony, Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook, and Byung-Chul Han’s The Burnout Society.

AF: It’s fascinating to see the figures for each book on Komubook’s Projects page – I applaud the transparency. Plus you can get cool pins, like a dog from Catananche. Or Cthulhu. Thank you again, Ali, for the interview, and please let us know when your translation of Catananche finds a publisher!

![Monument for Inger Christensen. Photo by David Stjernholm. Featured image for [o] by Kristi Maxwell.](https://atlengthmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Monument-for-Inger-Christensen_Kaare-Golles_002_Photo-by-David-Stjernholm-1280x914-1.jpg)