interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

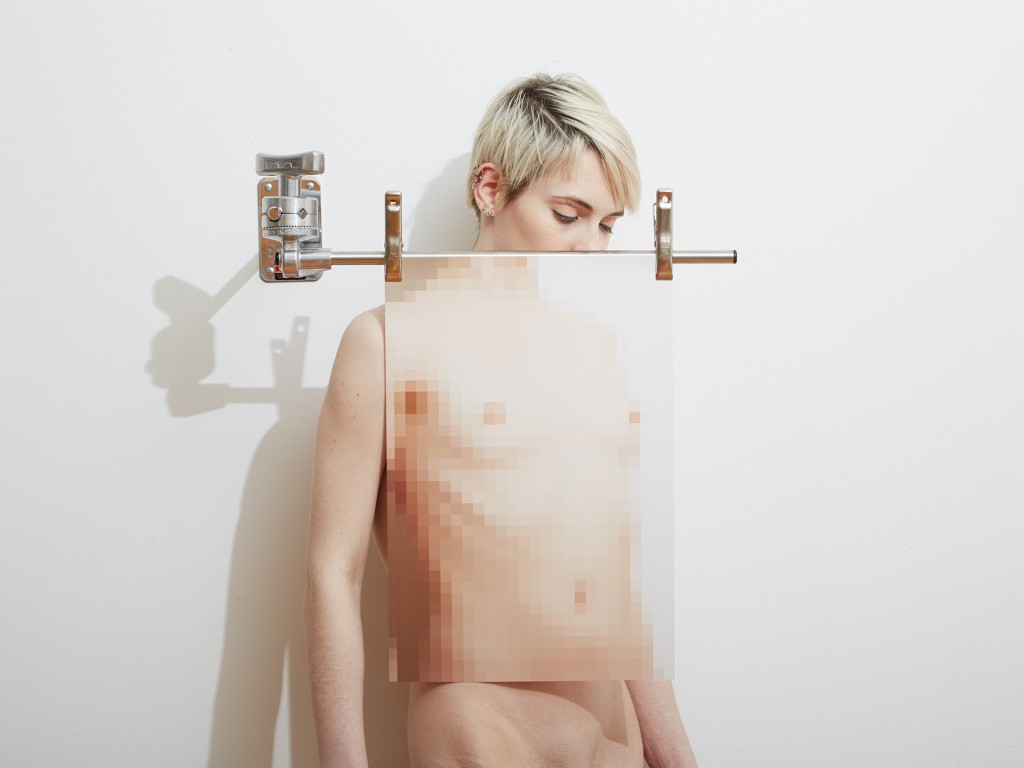

Adrian With Mosaic, 2015 © Bill Durgin

Adrian With Mosaic, 2015 © Bill Durgin

At Length: Your photographic practice, as a whole, engages with the human body. What initially inspired you to make this the focus of your practice?

Bill Durgin: I’ve always been fascinated by how the physical body how ages, the virtuosity of athletes, dancers, performers, and just how people inhabit space. For years I was reluctant to photograph the body as I wasn’t interested in the figurative photography work I’d seen. While working on an earlier series of narrative-based images, I became less fascinated with the before and after of the scene I was creating and more interested in creating something singular, something that did not have a before and after, something that existed only in one frame. It couldn’t be perceived as part of a scene that you would come across. This idea came to me of a torso draped with no arms or legs. I wanted to see if I could image that. I’d originally thought I would have to do it in postproduction, but while working with a friend who is a dancer, I realized how through contortion and perspective I could create this sculptural view in camera. I was hooked.

AL: The Fresh 2015 exhibition featured photographs from the “Studio Fantasy” series. Can you tell us more about this work—especially in terms of how it emerged from your previous series?

BD: While I was an undergrad at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, I saw a television ad for Lagerfeld Photo eau de toilet. It showed a photo session in a shabby chic loft with a stereotypically beautiful model shooting with a stereotypically handsome photographer, no other production staff. Shot in black and white, very diffused, the shoot was a flirtatious dream sequence. At the time I was working in commercial photo studios and the school’s darkrooms, sweating, getting dirty, smelling of chemicals, schlepping equipment, enduring the demands of anxiety-inducing production schedules…. I loved the irony of it, seeing the photographic shoot portrayed as fantasy while working in its much less glamorous reality.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pbS2ha5IQLY

I was reminded of this while shooting head shots for a friend. He brought a bottle of wine and offered me some. While I do love wine I can’t drink while I shoot and said so; there are too many variables to focus on, and I’ll inevitably mess something up. He was surprised and said he had a completely different picture of what I did on a daily basis. When I realized that even my friends had this fictionalized glamorous view of my studio practice the idea for Studio Fantasy came immediately. Unlike other series the name came first, and I started showing the edges of the sets and some of the banality around studio practice. In my previous bodies of work I carefully composed each image to avoid stray objects and supports. This series put those in the forefront. I wanted to depart from the set of rules I had laid upon myself, freeing up my technique and exploring some new ideas while still investigating new ways of imaging the body.

Fake Wine Spill, 2015 © Bill Durgin

Fake Wine Spill, 2015 © Bill Durgin

AL: In this body of work, you have maintained the human form as a central focus, but also incorporated photographs of objects without bodies. Why is this?

BD: Still lifes in the series are about making the banal beautiful, elevating studio tools and props to be the primary subject. Using gaffer tape to make a graphic tonal composition, the beauty of a plastic bag suspended from a C-stand, apple boxes leaning against each other with a print that visually erases one, a fake wine spill shot to reveal its inherent farce.

AL: In many respects, then, the studio, along with its various props, has emerged as a key subject. Can you tell us more about how you’ve explored this?

BD: “If I was an artist and I was in the studio, then whatever I was doing in the studio must be art.” – Bruce Nauman

The studio, specifically my studio, is the key subject in this series. Aside from the obvious titular reason, I’ve been interested in the labor of studio practice. I have always revered Bruce Naumans’s approach to working in the studio, going there everyday working through the boredom of being alone all day and making that the work. Also his approach to creative blockage, “It generally goes back to the idea that when you don’t know what to do then whatever it is you’re doing at the time becomes the work.” – Bruce Nauman

I use the studio as a blank slate from which to build an image. There were certain rules I set as my work working method: show edges of the set or parts of the studio, use minimal props, a single bare bulb light source, include any tool used including color charts. I start with an empty studio area and bring in whatever support catches my eye that day. When working with a model, I’ll direct them to where the focal point is and then we’ll improvise and refine a pose. I’ll then take part of that image, pixelate it, print it, then bring that back into the set and continue improvising and refining.

Priscilla With Color Checker, 2015 © Bill Durgin

Priscilla With Color Checker, 2015 © Bill Durgin

AL: It’s not just the studio that you examine, but this notion of the photographic space as well. What visual devices have you employed to examine these ideas?

BD: The camera itself is an editing tool; you are creating a visual space and omitting anything outside of the edge of the frame. The lens has a singular monocular view, which I exploit to achieve my composition, showing and hiding parts of the studio, the set, and sometimes the figure. “Studio Fantasy” is about making a photograph, not a documentary of what happens during the shoot.

I was looking at a lot of sculpture throughout this series. While I do see much work in person, I would always be looking at photographs of it in my studio. I was taking inspiration not just from the sculptures themselves but how they were translated into the photographic space. I treated my sets as a sculpture and documented them from a very specific perspective.

AL: The use of the pixilation appears to be a nod toward contemporary image consumption, through platforms such as social media, for example, but we wonder if there is something else going on. Can you expand on this element of the work?

BD: I saw an image on Instagram where someone had pixilated part of a body to fit the Community Guidelines. I was drawn to how the image looked more like a beautiful collage than a censored image. I could never find the image again, and perhaps it’s just the memory of that image that inspired this direction. I was drawn to the idea of using a form of censorship as a tool for incorporating a different dimensional plane within an image, like a collage. It also became a new way of abstracting the body and calling attention to the aspect of nudity rather than hiding it. The viewer becomes very aware of what is seen and what isn’t.

AL: How do you want your work to be received or understood in this context?

BD: I want the pixilation to be seen as a form of collage. I first saw it used in television news as a way to keep persons and incriminating documents anonymous. It was also sometimes used to hide nudity, often streakers at sporting events. Now I see it most often used on social media for the purpose of obscuring nudity, especially on Instagram. While I use it as a compositional tool, I also enjoy that it references anonymity and censorship.

Jen With Mosaic, 2015 © Bill Durgin

Jen With Mosaic, 2015 © Bill Durgin

AL: Overall, your practice presents itself as disciplined, formal, rigorous. How do you go about making what you do? What is your process?

BD: I usually start with a bare studio and an idea. That idea could be a sculpture I saw, a pose in a painting, a new piece of equipment in the studio, or just a piece of plywood leaning against the wall, and more often than not it is a combination of props and a pose. This idea is a launching point, something to set up before the shoot begins. When I get on set with the subject, a model, prop or myself, improvisation takes over. I select an area to be pixilated, print it out and bring it back into the set when improvisation takes over again. I’ll often have to do several prints, try different supports, a constant back and forth between staging the new set and improvising with it.

AL: Do you view your practice as a formal interrogation of the subject? If so, what are the key qualities or concerns that thread the different bodies of work together?

BD: My work is more of a personal interrogation of the subject(s). While there are definitely formal issues investigated, representation, figuration, compositional strategies, theories of perception, there’s also very personal motives and emotional content within the images. I’d say that the main elements that go through all my bodies of work are image construction and a constant push for the new ways to image the body through various formal and personal perspectives.

AL: Would it be fair to say that the “Studio Fantasy” series interweaves several theoretical/conceptual notions? For example, the photograph as constructed and mediated, the labor of the hand, scopic illusion and so on?

BD: Definitely. Since the beginning I’ve always focused on constructing photographs; it’s just what I’ve been drawn to do, and with each body of work a new set of concerns gets added: historical context, both photographic and art historical; the use of camera angle and perspective, and the gaze created by that perspective; studio labor; body image; photographic space as partial truth. Some images address more concepts than others, and “Studio Fantasy” brings in ideas of creating images in a digital age while the construction of those images finds its core in hands-on studio technique.

AL: The color palette of the series is very restricted, why is this?

BD: I wanted the studio to be the ground from which these images emerged, so that determined the palette. Being a minimalist, adding color wasn’t a concern. I guess my studio just isn’t very colorful.

Self Portrait, Gray Card and Multiclip, 2015 © Bill Durgin

AL: It’s also somewhat quieter than your previous work, less risqué. Do you think this helps to make photographs more accessible and palatable to art collectors? Or, if this not a concern or conscious shift?

BD: I actually thought this work was more risqué, bringing the topic of nudity right to the front. Perhaps the bodies are more recognizable, but there was no conscious effort to make anything more palatable. I wasn’t thinking of sales while making it, just ideas and experimentation.

AL: Following the Fresh 2015 exhibition, you were shortlisted for the Aperture Portfolio Prize. What impact has this exposure had on your success as an artist, and what is next on the horizon?

BD: It was an honor to be in Fresh 2015 and shortlisted for the Aperture Portfolio Prize. I definitely had a bump in exposure, but most of all it is validating as an artist to be recognized for your work. This was a new direction for me, so it has encouraged me to continue expanding, growing and experimenting with my work. Right now I’m working on a series entitled “Figure-Ground,” stemming from the principal in gestalt theory that a figure is perceived through its distinction from its background. I am layering several images from a single shoot, partially erasing and layering figures, blurring the boundary between what is figure and what is background.