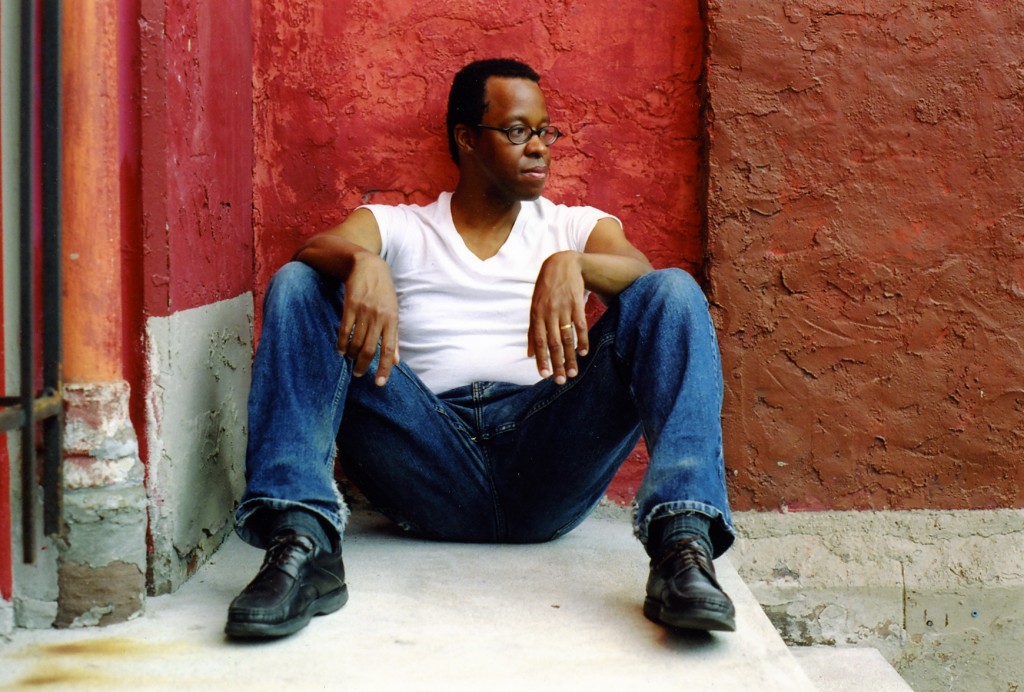

At the age of 49, pianist Matthew Shipp – who has recorded more than thirty records as a leader or soloist – is one of the most influential figures in modern jazz. As a musician, his occasionally forceful style of play, his dynamic use of the lower octaves, and his keen sense of negative space give him an instantly recognizable sound. His compositional style is deeply rooted in his extensive experience as a free jazz improviser and the idiosyncratic blues of Thelonious Monk, and it has more recently begun to incorporate elements of modern classical music, electronica, and hip-hop.

By the end of the millenium, based solely on the strength of his studio recordings and live performances, Shipp had already become a major figure in the jazz world. But in 2000, Thirsty Ear Recordings invited Shipp to curate their new Blue Series, where he proceeded to not only highlight some of the best and most interesting jazz artists working today, but also to tear down the boundaries within the genre. Artists like hip-hop sound collagist DJ Spooky, rappers Antipop Consortium, rock guitarist Vernon Reid, and electronica duo Spring Heel Jack were brought in to produce adventurous works, both on their own and in collaboration with jazz musicians, to create a daringly open blueprint for the future of jazz. This approach drew rave reviews and generated some much-needed excitement in a genre that suffers from a stuffy and forbidding reputation. But Shipp’s iconoclasm sometimes draws controversy instead of praise, as it did this winter when his remarks questioning the pre-eminence of elder statesmen like Herbie Hancock in the jazz world drew fire in the press.

Now, more or less coinciding with his ten-year anniversary as head of the Blue Series, Shipp has released 4D, which is billed as a summation of his career to date. A solo piano recording full of spacious new compositions and re-arrangements of jazz standards, it also includes startling takes on more unusual tracks like the French class sing-a-long “Frere Jacques” and the medieval “Greensleeves.” At Length spoke to Shipp about his new record, the mystical side of his musical philosophy, and getting burned out on the jazz world.

Click the player below to stream the title track from Shipp’s new record, 4D. Depending on your internet connection, the song may take a minute to load.

Matthew Shipp – “4D”

Ehren Gresehover: The first thing I read about this record from Thirsty Ear’s web site was that this new record would be a “synthesis and culmination” of all your work with the label.

Mathew Shipp: Right.

EG: And 4D, the title of the record, sounds like it refers to the fourth dimension, which to a physicist is the dimension of time. But there’s also a strong mystical tradition concerned with the fourth dimension, which had an impact on the Cubists. Jazz has a strong tradition of science fiction and mysticism. Were you trying to tap into that with this title?

MS: Yeah, that’s definitely a component and a product of a way of looking at the jazz universe. I mean, if you look at mysticism within jazz, there are a few known approaches. First, there’s the Coltrane approach, which is kind of a circular universe with a resonance not unlike Indian classical music, taking jazz and making it a very ecclesiastic music, not in a Christian way, but kind of in a universal consciousness way. And in Sun Ra a persona is created. He was taking aspects of Egyptian mythology, and Greek thought like Pythagoras and things like that to create a figure. And the generation of the musical universe comes about because of that mystery religion world view in sound. So I’m definitely coming out of that tradition – a mixture of both the Sun Ra and the Coltrane ways of using mysticism within the jazz universe. And the other thing about jazz, I mean actually when I play, I’m talking about the actual linear content of my playing. I mean, I sit down on the piano and I create lines in the same way Bud Powell or Bill Evans would, but I am actually always trying to get a universal equation when I do that. And I can’t define that, but I’m always aiming for the line that has some sort of elegance and for it to actually say something that is an equation of being of sorts. Mysticism is a huge aspect of my whole thing within jazz.

EG: In John Szwed’s biography of Sun Ra, he talked about how he came out of a pre-jazz tradition in African American culture based on African Zionism and Egyptian mythology, and how that adapted itself very well to sort of a science fiction.

MS: Right. You can take something like the Emerald Tablet and the idea of aliens coming to earth and get the idea that a lot of our so-called religions might be kind of mistranslations of some other text, which really does lend itself to science fiction very much even though it’s a mystical concept. If you deal with infinity, and if you deal with the fact that a mind is within the pool of infinity, and anything finite is connected to infinity, then if we have human beings, there can therefore be levels of mind infinitely above that. So what maybe religion calls angels were actually aliens? I’m not trying to get like… I’m not into flying saucers and stuff per se, but I’m just saying there is a mythology that goes with the music that Sun Ra did really tap into definitely and informs the whole idea of when you sit at the instrument. It’s almost like you are a mathematician from another planet. And you have the system of math in your head and that system of math allows you to generate an elegant language of sorts, and that’s the whole thought form that feeds the mythology of the music.

EG: There is something almost alchemical with the way music works. In some ways it seems very mathematical and very physical that that the sounds of all these harmonics and vibrations can be written as equations. But also it’s very much a mystical experience.

MS: Right. It’s so cosmic that you can’t even describe it. The great thing about the mystery of any music is that when it’s over you know you felt something good, but you can’t say what it was. You just can’t say what just occurred.

EG: If you could totally describe what music was doing then you wouldn’t need the music. Music is there because it does something that words can’t.

MS: Right, exactly.

EG: Bringing things a little more down to earth, I was really curious to what extent you set out to do this set of recordings as a conscious summation of what you’ve been doing lately. Was that at the front of you mind when you started planning the album?

MS: No, no. I think your whole past is always pressing on you, anyway, whether you consciously want it to or not. So in one sense any slice of space-time is a summation. But I guess I’ve always wanted to tie things up in a nice way, which you can’t ever do actually, but I’m always looking for that. I think I’m making a statement more of where I am. I guess just basically you’re always going to be able to put together everything you learn.

EG: When I was prepping for this interview, I came across one that you gave right around the time you put out DNA in which you said that record was kind of capping off a very frenetic period of your career and you were thinking about taking a break. And right after that, of course, you become curator of the Blue Series for Thirsty Ear and had yet another busy decade. Do you see yourself at a point now where you’re thinking about what the next phase is?

MS: I know what the next phase is. I’ve been thinking about it. I’m at a point now where I’m actually burned out from the jazz world and I would really like to take a break. I mean, I love performing, so I’m never going to get burned out from getting on the stage and playing. But what I would really like to do is take a break. I mean the thing about recordings is the mindset that goes with it. You have to prep for them, you have to set up a kind of a milieu for certain recordings to be accepted and you have to then put it out there and sit back and wait to see what happens. And I am kind of tired of it. I’m not saying that I’ll never do another album again. But I am really just kind of caught in the cycle of doing recordings. I actually consider myself gifted at that kind of conceptualizing and doing it, but I really want to just perform. But for the next cycle, this solo piano thing is really where I want to go. I mean, I perform solo a lot these days, and I really like it and I really think that I have complete freedom when I do it. So the next cycle is just to keep doing what I’m doing. You know, there’s no other all-electronic phase of any other big jump that I am going to do. I’m just going to play a piano because it’s a really nice thing to do.

EG: Are you going to continue your work over at Thirsty Year curating the Blue Series?

MS: Yeah. I mean I don’t really do that much. I used to really be involved with everybody’s recording and stuff, but as long as it’s still there I’ll probably be part of it. It’s definitely a cool thing to do because it kind of kicks me out of my own orbit a little bit sometimes.

EG: What you’ve done with the Blue Series has been consistently exciting. I feel like the worst enemy of jazz right now is that people are almost too reverent about it. They treat it like a big museum with a bunch of old stuff you’re not allowed to touch.

MS: [Laughs.] Don’t get me started. I’m with you 100% with that.

EG: The Blue Series has been doing something really great, not just for jazz, but also for music in general, by bridging some of these artificial boundaries that separate the genres.

MS: Well I’m just not into the reverence that we give to jazz’s past. Granted it’s a lot of great music, but so what? You get up in the morning and we all breathe the same air. Why pretend that if something was done in 1958 it has any more value than anything anybody’s doing now. I definitely feel jazz is in a deep freeze and the mindset of people that deal with jazz is really very problematic. Part of the Blue Series is me trying to develop for myself even a different paradigm altogether to deal with because the jazz paradigm is deadly, man. There are a lot of people to blame for it, but the bottom line is it’s an illusion and just a drag.

EG: Speaking of old stuff that’s not a drag, you have a handful of great re-arrangements of some older songs on the new record. A couple of them are definitely within standards in the jazz tradition. But “Frere Jacques” and “Greensleeves” are both unexpected highlights of the record. “Frere Jacques,” in particular is so percussive and surprisingly dynamic. How did you decide to do those two songs?

MS: Well I’ve recorded them before, actually. “Frere Jacques” was on Pastoral Composure and “Greensleeves” I did on a duet album with Matt Maneri at Hat Art [Gravitational Systems]. I like song books in general. They have a deep abiding place in people’s subconscious minds because they have just been around forever, and I like to mess with people’s minds a little bit by doing stuff with them. The thing about “Frere Jacques” is that it lends itself to that percussive, Prokofiev quality. I actually did it as a joke when Peter Gordon (who runs Thirsty Ear Records) was in the studio. And somehow it came up and I just sat down at the piano and did it. And I wasn’t keen on using it, but when the tapes were sent back he had listened to them before I did, he was begging me to put it on. And “Greensleeves” I just did at the end of the day. I played a bunch of staff and I was a little tired and I just started to bang away at it. I wasn’t planning on using that either, but when I listened back it seemed to be a proper coda for the album.

EG: I see you’re doing a European tour in April, but before that you’re going to be playing as part of the 40th anniversary of the New England Conservatory of Music, where you studied more than 20 years ago.

MS: 1983, you’re right.

EG: How does it feel to be celebrating that institution and to be looking back on that time in your life?

MS: I’m doing it as a favor for a friend. I’m not celebrating anything. I don’t believe in celebrating institutions of any sort. I’m against institutions; I’m against tradition.

EG: Very punk rock.

MS: I think Ran Blake is going to be there, and that’s one thing I’m looking forward to. They’re doing a bunch of these shows, some in Boston and some in New York, which is where I’m playing. Ran Blake is going to be there and I have a fondness in my heart for Ran. I don’t look at him as the New England Conservatory, I look at him as Ran Blake who happens to be at that institution. I haven’t seen him for years. But I have no nostalgia for that place or any place.