interview by Darren Ching and Debra Klomp Ching

Ethan Hill‘s portrait of W.M. Hunt © Ethan Hill

At Length: You’ve been collecting photographs for a long time. When did you realize you were a collector?

W.M. Hunt: It sneaks up on you. I didn’t set out to collect photographs. I bought one and found that to be a very intense experience because I didn’t really have any money. The whole thing seemed unreal. Why had I bought a photograph? It was an impetuous, daring action.

AL: It must be quite a thrill to have the exhibit for the Unseen Eye collection opening at the George Eastman House this month, as well as the book being released by three different publishers. Do you see it as a form of recognition, an endorsement of some kind?

WH: It is thrilling, and at the same time very dense, lush yet strained. There is a great deal of work, by me striving to place the work, of thinking in front of people and trying to keep that smart and varied. The notion of three different publishers is incredibly cool, and kind of slippery I think. As for it being a form of recognition, I will offer up the correspondence that Thomas Neurath—who runs Thames & Hudson, my primary publisher—sent to me, initiating the collaboration.

15 July 2005

Dear Mr. Hunt,

I was in Arles for a couple of days and of everything I saw there it was the presentation of your collection which impressed me most. I found it spell-binding and thought-provoking and on my return made enquiries about how I could contact you via my friend, Bill Ewing, who was kind enough to give me your email address. To come to the point immediately: would you ever contemplate working with us to fashion a book very much in the spirit of the Arles exhibition? I would be enormously pleased if your first response were positive and I am sure we could then figure out a way of exploring the notion even though you are in New York and we are here in London. You may not know a great deal about Thames & Hudson, but photography has been a mainstay of our list these last thirty years, and Bill Ewing and quite a few other people in your and his world would vouch for us, though quite often the books we undertake appear under imprints other than T&H in their American edition. Very much hoping to hear from you, I remain with kind regards and much admiration for the genial way you have fashioned something that goes far beyond the mere sum of its parts.Sincerely yours,

Thomas Neurath, Chairman

That was so astonishing really–how many people get a solicitation like that? Plus, it was a validation (and vindication of sorts) for four decades of obsession. I have always had huge issues with my own sense of self esteem, and those have been resolved in many ways by my life in photographs. In my heart of hearts, I feel that I am modest and intimidated, although it seems that much of my life in photography is characterized by single-mindedness and forthrightness. Ironies abound!

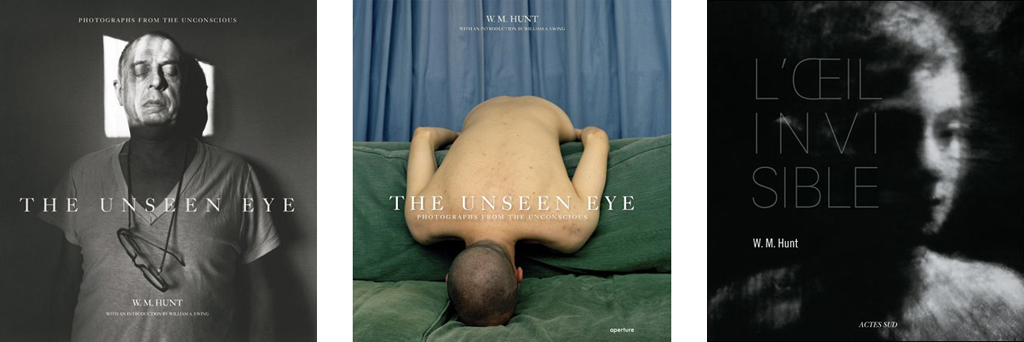

The three covers for The Unseen Eye: Photographs from the Unconscious. From left to right: Thames and Hudson photograph by Lee Friedlander; Aperture photograph by Carrie Levy; Actes Sud photograph by Erwin Blumenfeld.

AL: You’ve mentioned in the book’s preface that the photographs in the collection are “all portraits of me.” Could you elaborate on that?

WH: I make the point that early on I had an epiphany one night when I was looking at the dozen or so pictures in my apartment. I was in analysis, I did the dream thing in which you are all the characters, and, hey, the pictures were all me. At first I was mortified, because I thought that anyone walking into my apartment would know everything about me. Of course, the reality of that is that people would ask if I was a photographer. People don’t want to see.

AL: What comes to mind is that the book is akin to the cabinet of curiosities that aristocrats would display in their homes after their grand tours.

WH: I think of it more as bringing home magical things to insulate myself from the world. My early talks about collecting were called The Walls of the Dancing Bear or $#*! I Dragged Home. There is a lot of voodoo and juju connected to collecting. Two of my favorite museum rooms are the André Breton library wall installed in the Pompidou in Paris and the extraordinary surrealist Kunstkammer or Wunderkammer at The Menil in Houston. That whole place is like an oasis for your soul.

AL: What sort of “voodoo and juju” have you encountered through your collecting?

WH: I mean that I have encountered crazy stuff that seems to have miraculously presented itself to me. An image like the Alinari [Hooded performer on wire, 19th c.] is a unique jewel, and I swear it was as if it was shining in my eye across a room—it was meant to be. That has happened many, many times.

Elinor Carucci, Sleep (Eran’s Back), 1998 © Elinor Carucci

AL: When considering the proverb “the eyes are the windows to the soul,” it’s quite haunting not being able to see through the window.

WH: This doesn’t respond to that directly, but a part of collecting is like listening for the Geiger counter to go off. I have stood in stands at art fairs sensing that something was there to see. It isn’t that uncanny when it most often reflects that a dealer has taste and eye that resonates with mine. Think of the windows of the soul as doorways or entrances, invitations to use your mind’s eye to see. It is the power of your imagination taking you to a personal place and making the piece specific for you.

AL: “Delight in photography for me is the unique sensation of encountering a great image for the first time. My eye fills and my heart sings, and with the best ones, it happens over and over.” Is this experience becoming rarer?

WH: It was always rare. Greatness is special. There is a sea of good work out there, but the great stuff is hard to find. But when it happens, Zowie! I make my students locate and write about 25 great yet unknown photographs, at the end of their first semester. Last year two kids picked the same Roger Ballen image, and I just danced around with it because it was soooooo good. It was good because it broke lots of rules for me in its structure. Talent is amazing. I accept that most everything in museums and galleries is OK, and that I shouldn’t burden myself with imagining that everything is great, because it’s not—it isn’t. Don’t kid yourself. But then every so often …. I describe collecting as running around in a thunderstorm praying that you’ll be hit by lightning.

AL: Currently there are so many ways to acquire works—via galleries, auctions, online and directly from artists. What advice do you give to the novice collector in navigating the marketplace?

WH: Commit! Buy the fucking thing and keep moving. Look, react, COMMIT! Keep breathing.

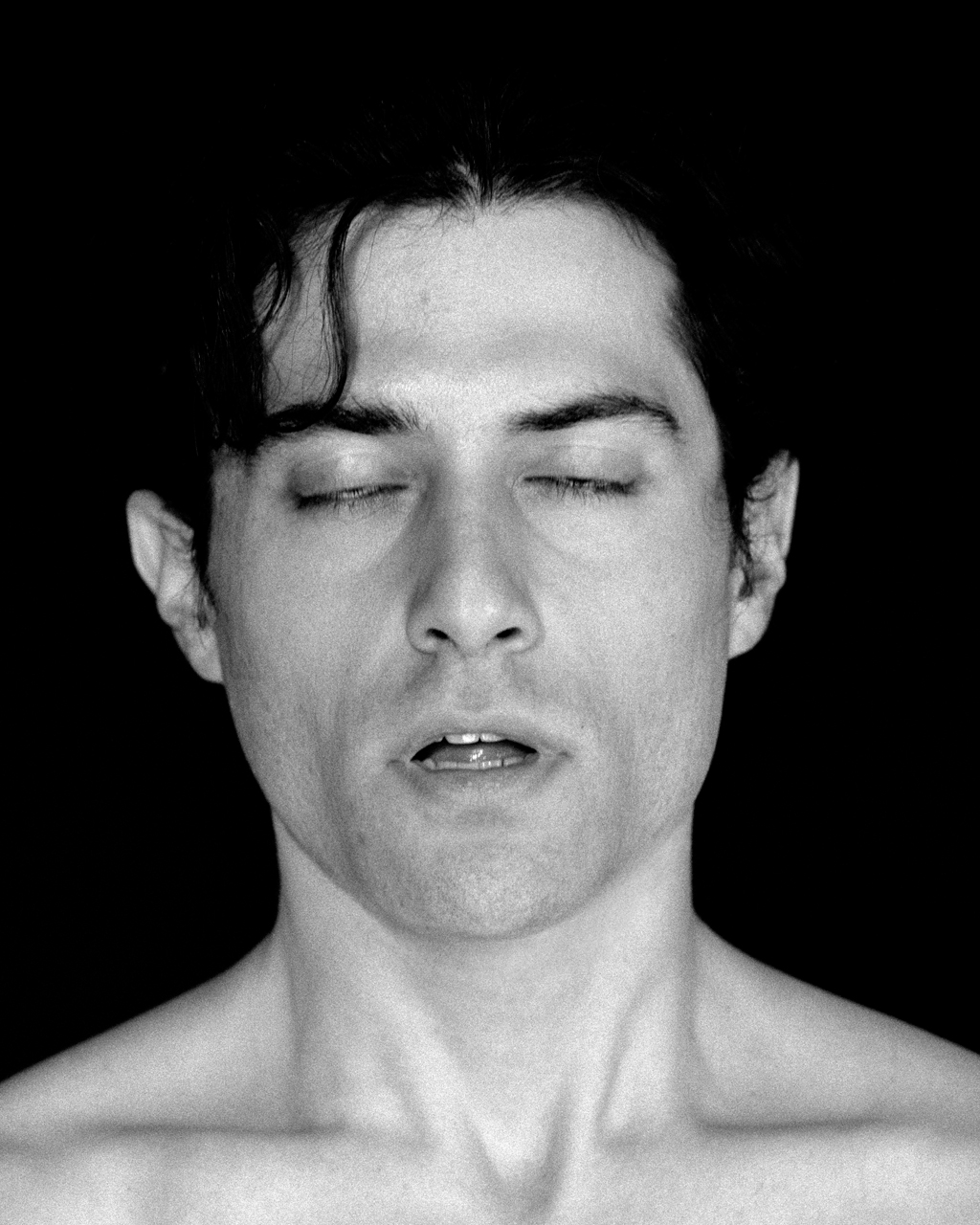

Frank Yamrus, Untitled (Paul), from Rapture, 1999 © Frank Yamrus

AL: Most of the images that represent your collection in the book are black and white. Is this because you seek black and white photographs, or are they the ones that usually make your heart sing.

WH: There is no good reason. Part of it is that my taste is very formal and restrained, at least graphically. Color work gets bogged down by its informational component. I like Alex Webb because he works and sees beyond that. It is harder for me to respond to Martin Parr, for instance—it doesn’t transcend its report. I get that work, but I never needed to own it. I was looking at a National Geographic book of so-called beautiful pictures at a friend’s house, someone who has fallen in love with photography and who imagines that I think his taste is crap. Everyone is entitled to their own way of seeing, but I do not subscribe to the notion that most stuff is good—it’s average. As a mean ol’ crack ‘ho, “I want good shit.” All those color pictures of sharks in a frenzy make for a dramatic tale—full of energy, color and INFORMATION—but my boat may remain unfloated, safe from their snapping jaws. Treasure the experience of that image that sends you reeling.

AL: One of the things we enjoyed most about your book is the journey that you take us on through the photographs. The magic is infectious and the ride wonderful.

WH: “Thank you,” says the crack ‘ho. “Just leave the money on the bureau.”

Frederic Weber, Untitled No. 77, 1995 © Frederic Weber

AL: Then, every now and again, an image is revealed that is rather more confrontational or difficult. Did you organize the book to keep readers on their toes?

WH: I will give credit to Mark Holborn, a well established book designer in London, who did the initial edit. He suggested that there was an operatic arc to the material, birth to death basically to infinity. That said, I found his actual layout to be deadly, with everything treated like a heavy-weight jewel—leaden. It had no music, no jazz. Ironically his son, Jesse—whom I have yet to meet—ended up doing the design. But the final edit, sequencing and flow are completely the work of Connie Kaine, longtime art director at Thames & Hudson, and me. We took Mark’s stolid edit and literally tore it apart but worked with that arc. He found the end note of transcendence, and that is where the book is headed all along. I am proudest of the sequencing, because I think the viewer moves through it trusting the journey. As an editor, I behaved as a spirit guide. I say in the preface to the book that it is like a dream, and I believe we found that. The liberating quality of a dream is that it doesn’t have to make literal sense. It’s an invitation into my head, so go with it. Also, you know that I am a very provocative individual. I want people to react! To the book, to the exhibition, to me! Étonne-moi!

AL: You have said that the decisive moment is as much for the viewer of photographs as it is for the photographer. What is that moment for you?

WH: John Szarkowski maintains that the only element of time to consider in photography is the moment the shutter clicks. That is the big moment. I think this disregards the equally unique and powerful instant when the viewer meets the image for the first time. Wham! I am interested in audiences. So much of art consideration seems to step past the notion of how something plays on the viewer. The part of me that loves the theater insists on that in visual art. Otherwise it is masturbation, which is great, but not the only or best game in town.

Debbie Fleming Caffrey, Untitled (Pattonville, LA, Child Covered with Blanket), 1970s © Debbie Fleming Caffrey

AL: Do you have to experience that moment to purchase a photograph or are there images that take a little longer for you to appreciate them?

WH: Overwhelmingly, I want that moment. The times I have talked myself into something have proved unsatisfactory. The moment can be drawn out over time, when you fall in love with a talent but don’t see the photograph yet. Sometimes you have to stay tuned. Look at F.A. Rinehart’s Shot in the Eye. I had seen platinum portraits of Native Americans, by an artist who was not Edward Curtis—that alone was news. I thought the work was splendid and overlooked in the marketplace, but because they were conventional open eyed portraits—not going to happen. Then one day…. Fabulous.

Also, I encourage collectors to recognize their taste so that they can communicate it to others, but to always challenge it. At some point, I consciously sat down and looked at landscape photography, because I never paid attention to it. I had seen work by Mark Klett and thought that he was really smart, that he had some sort of existential take on seeing. If you keep looking, one day you find that your instincts were totally on the money. Imagine finding a gem like A portrait of the Artist atop a small hill on his 30th Birthday, a self portrait of an individual—an artist(!)—silhouetted on a perfect hill. Great photograph.

AL: We love the Neil Winokur portraits of yourself and Chip that are included in the collection. Tell us a little more about them. Did you have them specially commissioned for your collection? The image of you is quite mischievous and fun!

WM: I always liked Neil’s work. Also, part of it is that I love Janet Borden. She is so, so smart and alive. I pay attention to her. She has been so committed to her artists, and I find that vision to be galvanizing. So, the commission actually includes three portraits: me, my partner Chip, and our-then neighbor, Mary Anne—whom we called our wife-in-law, because it was one of those perfect next door situations. We did the three and put them by the elevator. I put Chip and Mary Anne’s portraits in the absolute center of the exhibition in Rochester. They will completely freak out because they are both very modest. Again, that is me being a noodge.

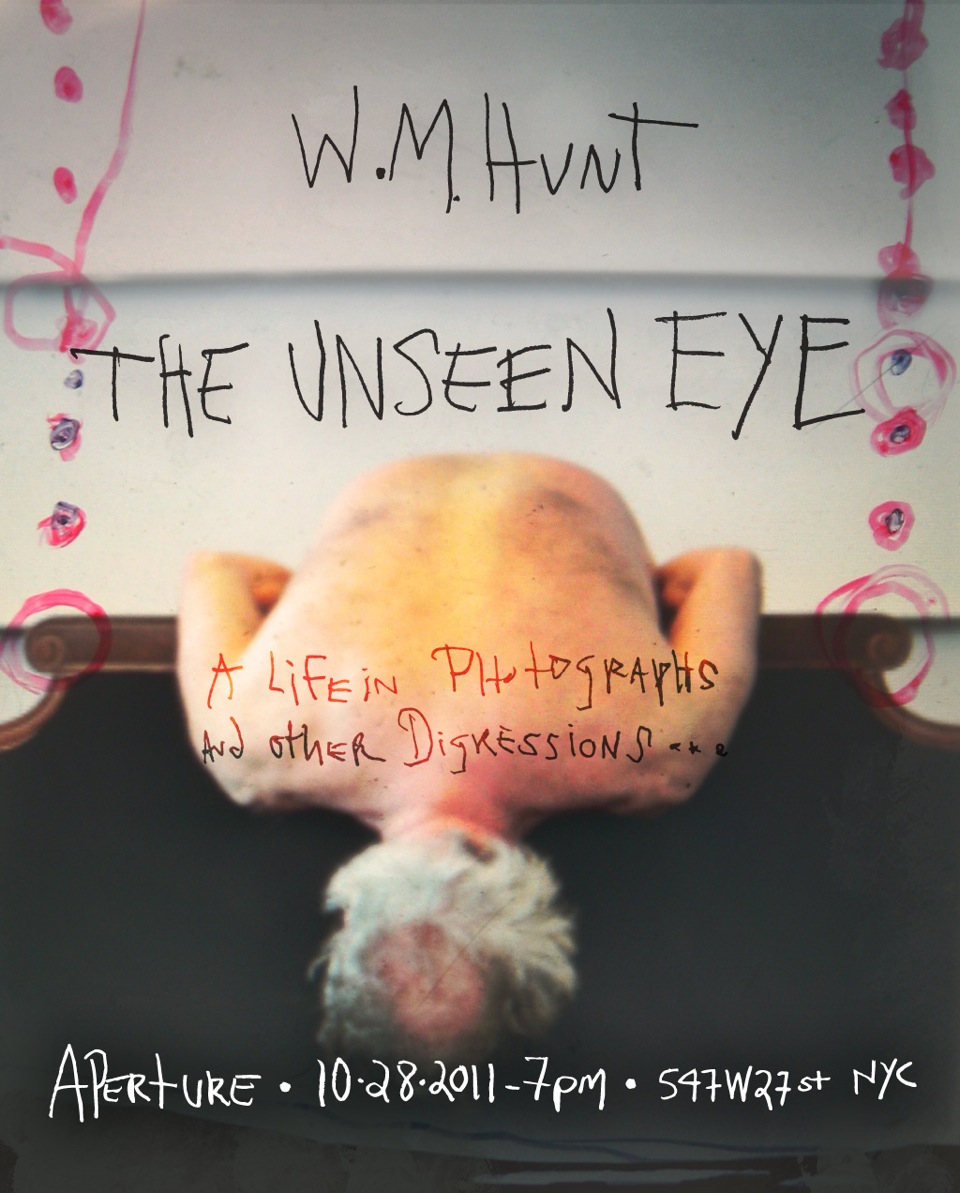

In the portrait of me, there is the red background—my choice—and a bubble of spit on my lips from licking them. Also, the print has a halo over my head. It is very special to me. But you notice in the book that I am vague about who it is. There is another completely transgressive portrait of me by Gerald Slota in the book, but since no one recognizes it as me, no one comments. Gerald and I have collaborated on a new image, riding on Carrie Levy’s cover image on the book. I wanted something to brand the performance piece I am doing at Aperture on October 28th and this is just right. It is rude, funny, and a little naked.

Gerald Slota and W.M. Hunt’s collaborative riff on Carrie Levy‘s cover photograph © Gerald Slota

AL: What is the pattern of your acquisitions? Do you purchase works as a result of encountering them unexpectedly, or do you consciously seek them out?

WH: Hmmm. One thing to bear in mind is that I am not really collecting anymore, as I indicate in the book. I worked out something for myself psychologically—over 40 years of collecting—and I am no longer driven to collect as I did. That said, I always made myself available as a collector. I was always open to seeing, reacting. I am still that guy, although now I don’t need to OWN them. The covetous part is resolved. I like the Joel-Peter Witkin line that I cite in the book, “The photograph is out there, you just have to find it!” Collecting is like walking around with your antenna wired for action.

AL: Your collecting interest is well known. Do you find that photographers/dealers are increasingly contacting you with suggestions of work you should look at?

WH: I get approached much less often than you would imagine. Approaching a potential client is an act of seduction I believe, and most people give up right away. Like in life, that’s not the way to be successful. People don’t listen to how others respond. Think romance, not seven minutes of carnal takedown. When I talk about portfolio reviews with artists, I encourage them to consider those 20 minutes as the meeting, the flirtation, and the taste of more to come—not the marriage.

AL: For 15 years you worked as a dealer—first with Ricco/Maresca and then Hasted Hunt (more recently Hasted Hunt Kraeutler). Has this experience influenced your collecting habits at all or how you relate to photographs more generally?

WH: One big difference was liking and respecting talent that I did not need to collect, but whom I felt I could talk about and present. You really do want to LOVE what you have in your inventory—at least I felt this way—so you could talk about it with conviction. As you know, dealing is a lot of work.

AL: Do you think upcoming dealers benefit from building their own collections? Would you advise them to do so?

WH: Sure. Many dealers were collectors before they became dealers, so they have feelings about and insights into collecting. Collecting is so personal—or at least what I consider to be good collecting is—that I can’t imagine another way into it. I am sure it happens, but it isn’t my experience so I can’t relate to it.

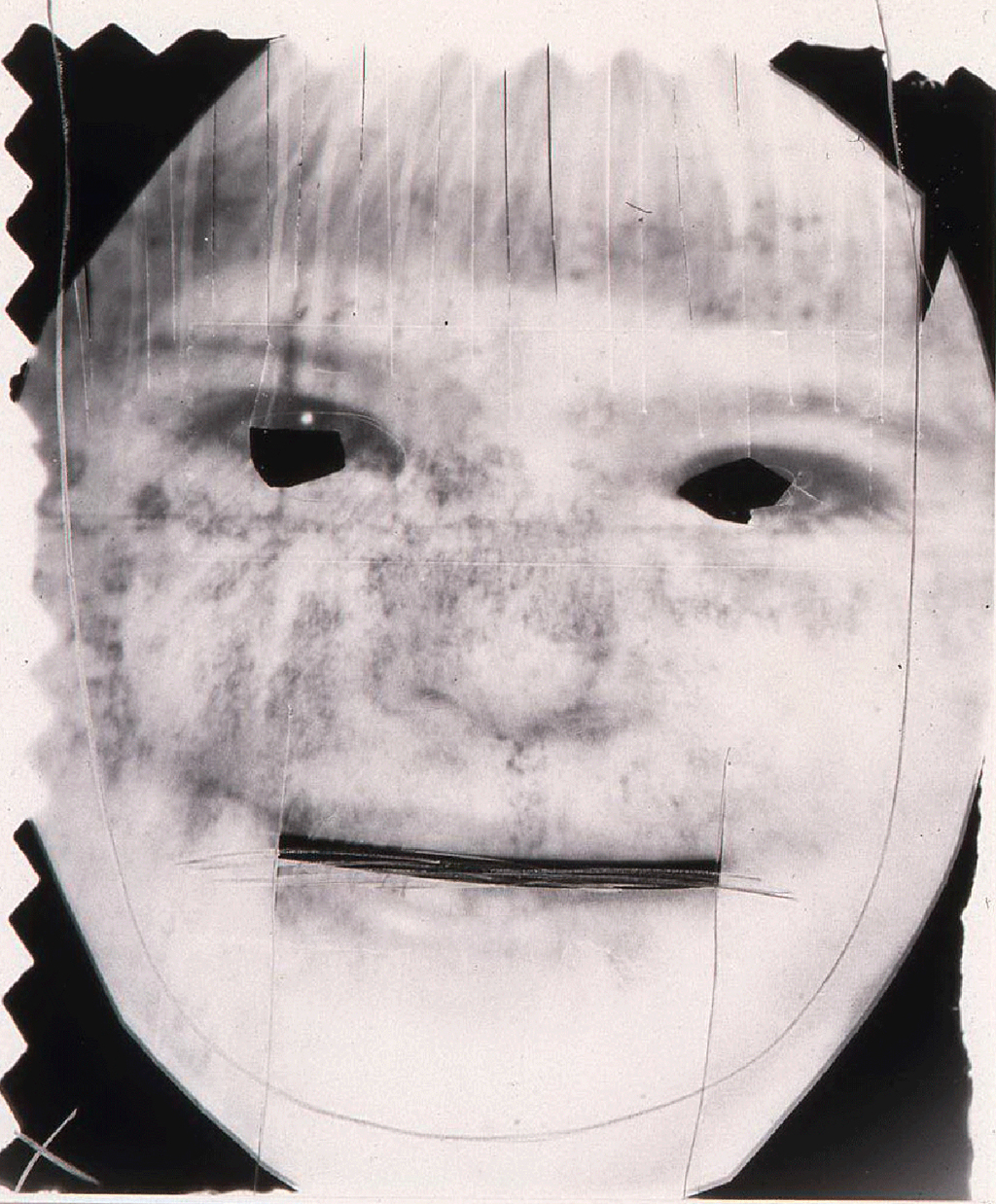

Gerald Slota, Untitled (Head No. 1, Freckled Boy), 1996 © Gerald Slota

AL: We’re often asked how to start a collection. Do you think it’s important to consciously purchase images that fit into some kind of parameter? Or do you think it’s a more organic process?

WH: I don’t know. It is hard to persuade someone to collect. A couple of acquisitions, sure, that is not so hard, that’s just advice. “I think this is a good one.” I will say that, as a dealer, I always offered my own opinion. “For ME, this is the best one and here’s why.… Now what do YOU think?” Talking someone into something is a waste of everyone’s time and energy. Also, I always found it hysterical when a client would say that they had to talk to their husband. I always wanted to pull out my phone and get them on the line. As a dealer, I was not blessed with patience.

AL: There are some very difficult images in your collection, which include Richard Drew’s image of the falling man from 9/11 and Thomas Howard’s infamous and historically important photograph of the execution of Ruth Snyder. What’s the importance of such imagery to you as a collector?

WH: I try to downplay their importance and to place the images in the larger context of the whole collection. The reasons why the images are iconic have to do with many things like timing, framing, seeing. They are not more important than other works in the collection, although presenting them involves some extra considerations, because they violate the sensibilities of many people and I don’t want to brutalize visitors to the book or to a show. Actually, I wouldn’t hang them in my home. As a collector, I want to have them, but I don’t need to see them—I know where they are.

AL: The range of photography in The Unseen Eye is quite remarkable. There are images from luminaries such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Harry Callahan and Diane Arbus to contemporary practitioners like Bill Armstrong and Amanda Means—as well as works by unknown photographers and vernacular works. What are your thoughts on the collecting of works by unknown photographers and vernacular works? Ultimately, does it make a difference to you?

WH: Absolutely. What distinguishes this collection is its inclusiveness. It is the history of photography considered through a very specific sensibility—mine. The urgency of collecting most often outpaces the availability to pay for it, so there was relief in finding inexpensive and amazing stuff. I even bought frames when I was out of money, in the hopes that the elves of photography would break in and fill the frames with beauties. It never happened…. Also, there are probably a dozen photographs in the collection that I have NO IDEA of where they came from.

Phyllis Galembo, Omolu, Brazil, 1987 © Phyllis Galembo

AL: Are you planning on bringing some of your other collections to the public eye?

WH: There is another collection of images of American Groups before 1950 that those elves I just mentioned really did hide under my bed. As you know, the Houston Center for Photography hosted an exhibition last year. I will do something more with that in time. Also, the vernacular work in the no eyes collection will find a separate life.

AL: The images of American Groups are often really quite amusing to look at. We have a few cherished group photos from our past—swim team, high school graduation—that never see the light of day. The images in that collection are anonymous, formal and displaying pomp and circumstance. What’s your connection to the imagery?

WH: There are also many groups that are chaotic. I like the opposite end of the spectrum just as much, those images are, in fact, harder to find. There are a couple of elements which interest me: how the crowd itself behaves—orderly or a mob—and then how the photographer chose to see it, to frame it, to capture the crowd within the shot. These images don’t suggest much of a personal reading in the way they do in the collection featured in the book. Right brain versus left brain maybe.

AL: What’s next for you? Is your collection complete?

WH: James Bond, “Never say never.” It has been very, very difficult for me since I left my gallery situation. I have projects that I am not so public about, but they are photographic and collaborative. My success as a collector, and as a dealer and strategist, is based on showing up as much as anything else, and that continues to lead me into a very full and exciting life.

W.M. Hunt (Bill Hunt) is a New York-based collector, curator and consultant, a champion of photography. He is responsible for introducing many major contemporary artists in the US, including Luc Delahaye, Julian Faulhaber, Andreas Gefeller, Erwin Olaf, Martin Schoeller, and Paolo Ventura, among others. His Collection Dancing Bear is the subject of a new book, to be published this fall as The Unseen Eye: Photographs from the Unconscious by Thames & Hudson (UK) and Aperture (US) and as L’Oeil Invisible by Actes Sud (France). Highlights of the collection have been exhibited in Arles, Lausanne and Amsterdam and will go on view at the George Eastman House in October, 2011. He was one of the principles in Hasted Hunt (more recently Hasted Hunt Kraeutler) and Ricco/Maresca Gallery.