You may also download and read this story as a PDF.

1.

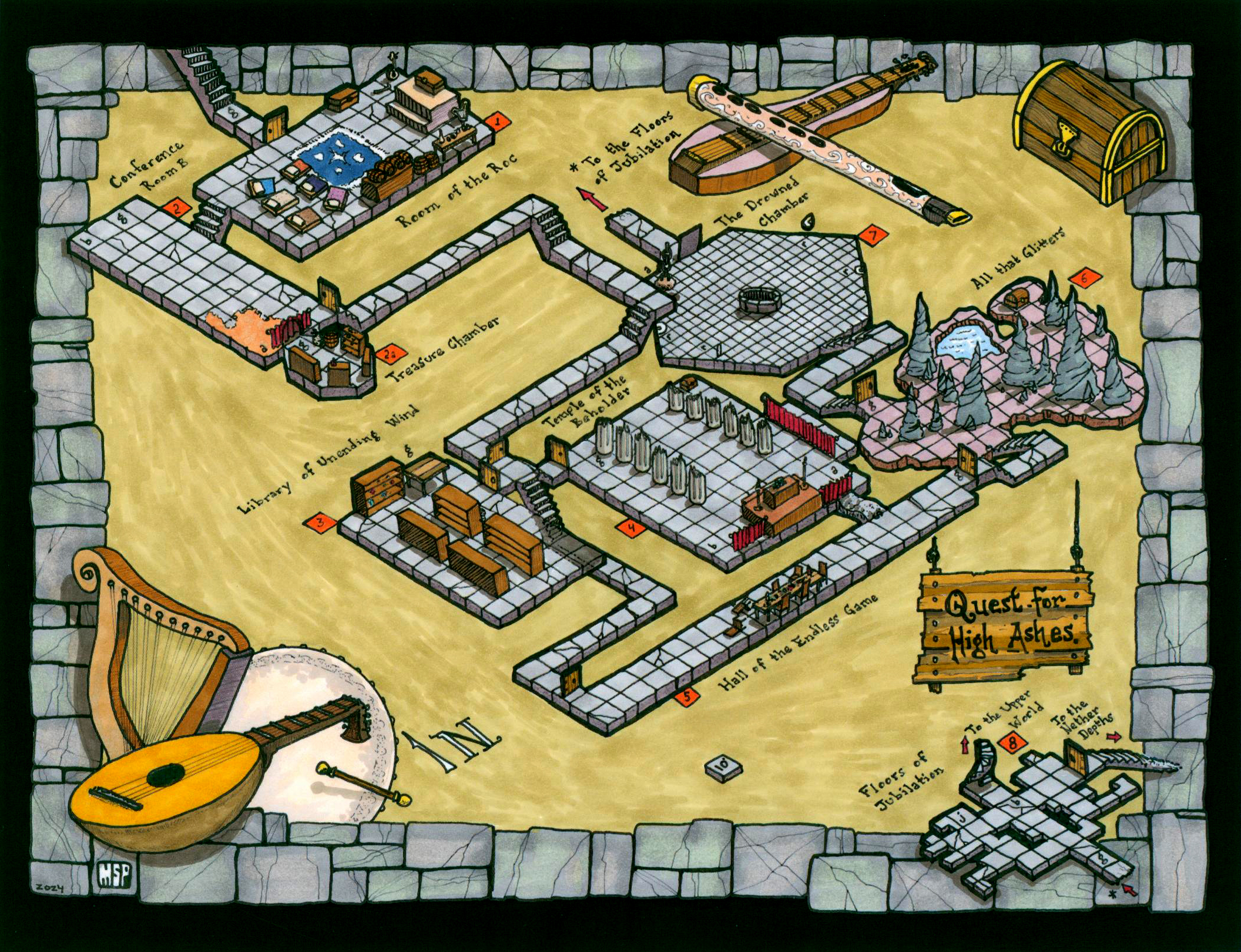

“Fuck you fuck you fuck you. Fucking American army piece of shit,” Sa’ad al-Azawi chanted behind the wheel of his BMW. He couldn’t recognize his own city, he couldn’t navigate it. He just wanted to hop across the July 14 Bridge to the manicured center of the city’s power, Baghdad’s palm-lined answer to the Washington Mall, soon to be home to the occupation headquarters. A tank blocked an on-ramp. We had to circle west along the Tigris River and then back east again to get to the Rashid Hotel.

Baghdad’s map had become malleable, old routes across town melting away like mercury and reforming in odd places. Americans had closed some roads and bridges with checkpoints. They had cut others with bombs. Buildings were missing in action. Pits of rubble had replaced homes, like an entire block that included a Saddam safe house behind a Mansour restaurant. A bunker buster had buried a three-story house in a pit 20 feet deep.

Along the approach to Baghdad, every hundred yards or less, a killed car askew beside the road — either a rotting driver, shot to death, or a charred car frame from a direct hit on the car by some kind of bomb. (Rocket? RPG? Mortar? So early in the war, I certainly couldn’t tell.) Bullet casings at every intersection, detours around each part of the highway bombed into a moonscape. A bloated dead donkey blocked the bridge across the Tigris in downtown Baghdad. You could date the bodies in the cars and sometimes on the sidewalks by their shape and smell. Within days of death the skin turned black. As they decomposed they bloated to twice their normal size. And they smelled stronger than anything I’ve smelled before, like that rush up the back of your nose from your stomach just before you vomit, and then blooming into something worse.

That’s what you could see up close. Wide-angle: the bombed buildings, the ubiquitous black smoke. (Why? Who knew. Things just seem to burn during wars, often random things like a junkyard full of old tires, or a warehouse, or the papers in a government building.) The entire city of Baghdad, it felt, had been tipped over on its side and shaken. Now its people were washed over the sidewalks, driven but directionless. City streets that a month before were full of traffic, lined with produce stands, pharmacies and jewelry stores, had been transformed into an alien landscape, often impassable, barely recognizable, like those microscopic images of human skin that show tiny predators foraging in our pores, the only reminder of place and scale a pylon that’s actually the base of an eyelash. The warped physical environment catalyzed the psychological change that began gestating for Iraqis during the months of drum-beating and posturing leading to Shock and Awe: a sense of possibility and change yoked to fear. The destruction of the country and its institutions left an uneasy vacuum for the mind as well as the body.

It wasn’t immediately clear to me, but it was clear to Sa’ad al-Azawi — and, it turns out, to millions of his compatriots — that all this destruction would require each and every Iraqi to concoct a new identity to fit the new taxonomy of power. Iraqis had a very intense personal relationship with the state, and had long needed to define their political, sectarian and religious selves in relation to a capricious and seemingly all-powerful leader, who might kill them if they unwittingly projected a whiff of sedition. Saddam and his security services had made the rules clear for decades.

Now new powers would rewrite the rules, and men like Sa’ad al-Azawi didn’t know who those powers would be. In that environment, it was no wonder that Sa’ad al-Azawi felt suspended, adrift, fluid: Not just free to reinvent himself, but required to do so. Most of Iraq, in a state of confusion, embarked on a similar self-reinvention project at the same time. The road map had literally changed overnight. The political hierarchy had vanished. Many of the old psychological reference points had melted away with the Ba’athists; the old habits remained, but their raison d’etre, and their enforcers, were gone.

2.

Sa’ad al-Azawi was handsome, skinny, dark, with a long, vertical, equine face. He had the twitching mannerisms of a nervous man, always fidgeting with his keys, moving his hands, pacing with small steps, looking away, around, and back at you. He smoked not for pleasure but out of compulsion, wincing with distaste as he took a drag. His hair was cropped close but the gray patches showed anyhow. His eyes were dark, dark brown, but I remember them as somehow black, brooding, and impregnable. He talked at a fast clip, imperfect but confident English.

He had fished us out of the crowd at the Palestine Hotel on April 10, 2003, two days after Saddam’s government fled. The hotel lot on Baghdad’s east bank was teeming with foreign journalists, hundreds of new arrivals from Kuwait and Jordan who like me were looking for a place to stay and a way to begin reporting. Iraqis who spoke English or owned cars had likewise flocked to the Palestine to offer their services at amazing inflated rates. $200 anyone to drive around in a jalopy with a sullen man who hardly speaks?

The U.S. military had put down some barbed wire, some APCs and tanks were parked around the neighborhood, and the hotel entrances were so packed with people it took a quarter of an hour to get from the street to the lobby. I was traveling with Essdras Suarez, a photographer from The Boston Globe, and Rebecca, a Lebanese we had seduced away from a guest relations job at the Kuwait Hilton in order to translate for us. She knew next to nothing about Iraq, but she was smart and game, she spoke the language, and she knew from sectarian war, having grown up during some of Lebanon’s worst fratricidal excesses. We were equipped to work on a basic level.

Someone in the crowd overheard me saying I was from The Boston Globe and shouted: “Bostonglobe! Bostonglobe! You are Bostonglobe! A man is looking for you.” For me? No one knew I was in Baghdad except my editor. Instantly I was suspicious, on the alert for a scam.

My wariness was misplaced. It turned out that Sa’ad al-Azawi had been asking all day whether any Boston Globe correspondent had yet appeared in Baghdad; he had promised the last correspondent in Iraq that he would resume work for the paper as soon as any of its reporters returned. The random man led me to Sa’ad al-Azawi, who embraced me tightly, like we had a long history. I hugged him back, susceptible to the smallest gesture of familiarity and affection.

Under the circumstances, the enthusiasm and warmth felt entirely normal. We’d all spent the last three weeks in shell-shock — some, like Sa’ad al-Azawi, because of Operation Shock and Awe in Baghdad, others, like me, from the cacophony of smart bombs and artillery exploding in southern Iraq. We were rattled from the constant sounds of gunfire, artillery, and bombing, and we were all distressed from constantly witnessing death. People tended to turn more readily to one another for comfort, hugging strangers or sharing odd, brief moments of communion.

Elizabeth Neuffer, the Globe’s UN correspondent and a veteran of Iraq coverage since the first Gulf War, had enthusiastically introduced Sa’ad in an email as “the wonderful Sa’ad al-Azawi, our loyal Baghdad driver … our eyes and ears in Baghdad.” Some of our reporters had tried calling him during the war to hear first-hand about the toll on Baghdad, but after one or two brief conversations it proved impossible to get through. By the time I got to Baghdad after several weeks camped on the roadsides of southern Iraq and a harrowing drive through the frontlines to the capital, I had completely forgotten about Sa’ad al-Azawi. My memory of The Boston Globe’s institutional connections to Iraq had momentarily shorted.

When he found me, he immediately asked about Elizabeth and briefly brought me up to date. None of his family had died or been injured, he said. He had evacuated them to a Sunni village outside of Baghdad, and had stayed in the capital as long as he could to make sure his house wasn’t looted. By the third week he couldn’t take the bombing anymore and joined his family in Sunni-dominated, bucolic Diyala Province. Roughly an hour’s drive from Baghdad, it was a popular locale for Ba’athists and other well-to-do Baghdadis to build weekend getaway homes in the date groves. The day Saddam fled, Sa’ad returned to Baghdad, expecting (so he said) to hear from The Boston Globe that he was needed for work. He had money and a generator belonging to Elizabeth, and was eager to start.

We piled into his black BMW and got a quick tour of the city, whose war-scrambled layout was harder than ever to decipher. On the east (or left) bank of the Tigris –called Rusafa in Arabic — we saw the commercial downtown and our future home, the mixed-sect upper-middle class neighborhood of Karada. (Later it would become the last semi-safe area outside the Green Zone.) We saw churches, mosques and Husaynia, small prayer halls for the Shi’ites; electronics shops, DVD stores, fancy restaurants, multi-story hotels, all shuttered for the duration of the war, now removing the boards from their windows.

3.

It was Friday. On Inner Karada Street, Baghdad’s middle-class mall, men on the sidewalks stared angrily through the windows of Sa’ad’s BMW. The people who lived and shopped in Karada were more likely to worship money than some obstreperous cleric. The churches got some traffic, but the mosques seemed equally neglected by Sunnis and Shi’ites. Karada was an idyllic neighborhood, its secular residents bound by pragmatism; American war planners had intentionally spared it as much damage as possible, considering it a friendly area and an important quarter for post-war Baghdad. Still, some bombs had struck the neighborhood, leaving a twisted truck chassis here or a crater in the middle of a lane there.

At the time, Baghdad was a patchwork of neighborhoods usually dominated by one sect or another, but with lots of intermixing. Karada was exceptional even then for its blurred boundaries. Historically home to some noble Shi’ite merchant families, Karada had attracted secular, middle-class Iraqis from all sects because of its vibrant commerce, proximity to Baghdad University, and waterfront streets. Its denizens were not for the most part stalwarts of the regime; they were more likely to have earned or inherited their wealth than to have profited from one of the Ba’athist state’s highly remunerative sinecures. The neighborhood was poised to be the unofficial capital of a new Baghdad, embodying all its ideals — harmony among sects, zeal for commerce, religion observed quietly in the background.

It was flanked on one side by the river, which oozed brown rather than flowed, and on the other by the smokestacks of the Baghdad South power plant and the plume of the Dora refinery, where they just burnt the natural gas byproducts of the refinery process. (Why save it or sell it when oil was basically free?) On that second day of “liberation,” Karada’s denizens wanted to keep out the predators who were stripping bare every home, office and government building, burning anything they couldn’t carry away. Karada’s merchants would brook no such anarchy; at every intersection, shopkeepers had erected checkpoints.

Saddam in his grandiloquence had dubbed the destined-to-be-glorious 2003 war against America the “Marakat al Hawasim,” the Decisive Battle. Iraqis quickly adopted the word to describe the “decisive ones” — the looters, thieves, and opportunists, the poor and the greedy who stole Iraq blind during and immediately after the fighting. The hawasim were everywhere, stripping molding from public buildings, loading air conditioners from the university onto donkey carts under the indifferent eyes of U.S. soldiers, trashing the national museum. High-class hawasim emptied banks and munitions dumps. Malevolent political hawasim burned incriminating Ba’ath Party records. Americans counted themselves among the hawasim, availing themselves of cars from Iraqi government depots and palaces, sometimes handing over vehicles with a nod to embedded journalists or random Western civilians.

Not in Karada, though; this was a neighborhood of businessmen, and they had no intention of waiting for a government or soldiers to come to their protection. The U.S. military might not shoot looters on sight, but Iraqi businessmen would be thrilled to.

“I want people to know that not all Iraqis are lawless and violent,” Fahed al Jabouri declared to me. He was bald, with a pot belly and a tucked-in shirt, and seemed upper-middle class. He held his AK-47 with familiarity but not with a fighter’s swagger. He was the chief of a vigilante band on a busy corner of Inner Karada Street. The merchants’ placid faces belied the violence they were prepared to dispense at a moment’s notice. Some held chunks of concrete, others clubs or twisted lengths of rebar.

This wasn’t raging street justice though: these men were imposing law and order with the blessing of the community, in the form of a crowd of festive onlookers and a local cleric, in effect supervising the checkpoint. “We want the American Army to know these people are not fighting them. They are establishing security in their own neighborhood,” the cleric, Imam Faris Jaber al-Halo, told me.

“When the hawasim finished with the government buildings and the schools, they started to come into our homes,” Jabouri said. “We will protect ourselves.”

Just then, the men at the checkpoint stopped an Iraqi driving a bus. His family sat in the front seats. The bus overflowed with government furniture: sofas, desks, cabinets, and the like.

“Excuse me,” Jabouri said. “We have business.”

The merchants pulled the man from the bus and threw him to the ground. Jabouri joined them in a circle, kicking him the man as his wife and children watched.

The beating over, Jabouri returned to our conversation without skipping a beat. “We don’t need the Americans to protect us,” Jabouri said. “We’ll protect ourselves.”

4.

Further into that first Friday afternoon drive, we crossed the Tigris into Karkh, the west or right bank of the river, and approached the seat of government: Saddam’s palace, his triumphal arch, the one decorated with Iranian skulls, to commemorate the disastrous Qadisiya, the 8-year bloody draw of a war between Iran and Iraq in the 1980s. We were in the future Green Zone. The architecture in this serene, wealthy residential area around the government buildings was ugly and Ba’athist — two-story villas with tightly clipped hedges, tinted windows, and ornate porticos over the windows and doors, curlicues drawn in cement. Lots of pink marble and gray granite accented the facades. These were the villas that in short order would house Iraqi official who wanted to be near but not in the Green Zone .

We kept getting lost trying to find our way around American checkpoints. The unsmiling troops were jumpy; already many of them had weathered attacks by suicide car bombers.

Just the night before, on our drive north from Basra to Baghdad, we’d camped overnight with a platoon from the 3rd Infantry Division at an overpass just outside the city. We were terrified to drive downtown in the dark. The soldiers were still on a combat high from days of gun battles, and they were camping in a patch of silt littered with the bodies of the men they’d shot the day before. At night Iraqi fighters were still firing at the platoon. It stank, it was scary, the men were on edge. Just after dark, a white car drove up the highway. Its driver didn’t hear, or ignored, the warning shots fired by the night guard, and didn’t (couldn’t?) see the tiny sign on the road, in English, ordering drivers to stop for a coalition checkpoint. The frightened soldiers fired a heavy machine gun, the red tracers drawing neon lines through the night. They looked fake, like Star Wars special effects, except for the insistent pounding noise, which echoed in my stomach the way bass does at a club. The car suddenly careered, its wheels screeching on the pavement, and came to rest a few meters beyond the checkpoint’s far side. The reality of the thudding bullets and skidding car jolted me out of an unreal trance, slamming into my gut with the force of a foot. In the morning we saw the driver’s corpse slumped over his wheel — a civilian, it turned out, with no weapons or explosives in his car. “Too bad,” a soldier said. “He should have stopped.”

The image of that dead driver still vividly in my mind, I ordered Sa’ad al-Azawi to slow down and approach the U.S. checkpoints with care: hazard lights flashing, 5 miles per hour, both hands visible on the wheel. But Sa’ad couldn’t believe that the same “fucking American army” that had bombed his city was now controlling its streets and telling him, an Iraqi, what to do. He approached checkpoints at full speed and only slammed on the brakes at the last minute, when the frightened soldiers raised their guns. Then he’d shout, “Jaish Amriki ya hara!” It was one of the first phrases I learned in Arabic, and it roughly translates as, “American Army, you are shit.”

“They won’t shoot us, don’t worry,” he assured me.

“They absolutely will fucking shoot us,” I shouted back. “You can’t do that, or you’ll get us killed.”

My protests were futile; Sa’ad could not control his rage. He was not alone. Everywhere a national temper problem was in evidence. At intersections, traffic would gnarl to a halt as anarchic drivers swarmed into oncoming lanes and sidewalks in search of shortcuts. Men brandished guns and screamed out of their car windows. It took hours to make even the shortest trip through the city center. At the newly erected checkpoints Iraqis recoiled at the invasive searches, outraged that an American with a gun might — for no apparent reason — decide an office worker wasn’t allowed to cross a checkpoint to the downtown building where he worked. Looters from lower-class neighborhoods roamed wealthy inner districts balancing menacing lengths of pipe over their shoulders. Those with property to protect wore pistols ostentatiously tucked into their jeans. Sa’ad was a bit player in this angry national drama.

He drove fast, taking curves recklessly, screaming at the Americans. He smoked three packs of cigarettes a day. And on the third day we were together, he suddenly started to pray. He came from a Sunni tribe, but he told me he was a Shi’ite, and he started praying as Shi’ites do, kneeling and pressing his head to the ground on a small round cake of hardened earth from Karbala. The most devout press so hard they create a permanent black bruise in the center of their forehead. In a day, Sa’ad bore the bruise of newfound devotion.

Out of old habit, Sa’ad al-Azawi wanted to please the Iraqis in power. In Shi’ite east Baghdad, he prayed like a Shi’ite. In Sunni west Baghdad, he talked with bluster about his powerful Sunni tribe. In Christian neighborhoods in the city center — the Christian minority was mostly Ba’athist and supported the regime — he reminisced about his old job at the Ministry of Information. Without a regime hierarchy, and with armored Americans asserting themselves at street corners everywhere, Sa’ad’s reflexes were confused, flexing and grasping at random as if a mad doctor was striking all his joints with a little rubber hammer. Surely Sa’ad knew he was a Sunni, but he didn’t know how that would play now that Saddam’s Sunni regime was in hiding. Until he knew who was going to take charge, aside from the Americans, he was going to hedge his bets, appealing to anyone and everyone he could. He could start by expanding his sectarian credentials, developing Sunni, Shia and mixed identities. He would also blend his political record depending on the audience, hinting at his affection for the Ba’ath when speaking to some members of the old Iraqi elite, or bellowing his rage at the regime’s atrocities when speaking to its victims.

He took us to meet his wife, a slight, pale and sweet woman who covered her hair. His wife was as placid as Sa’ad was nervous, sitting with her back straight but her facial features relaxed into a smile. She didn’t speak much English, and Sa’ad seemed uninterested in including her in a conversation. Their newborn baby, only a couple of months old, slept peacefully in her arms during our visit. Sa’ad said the bombing had upended his child, making him weep inconsolably at night. I believed it. I felt like weeping all the time.

5.

Within a week of my arrival, Globe colleagues joined me at the Hamra Hotel: Elizabeth Neuffer, the seasoned correspondent who was going to take control of our Iraq coverage, and Anne Barnard, another metro reporter from Boston. Anne and I made common cause as newcomers to war reporting. Anne was delighted and fascinated to find herself in Iraq just as it was opening to the world after decades of repressive dictatorship; it reminded her of the years she had spent in Moscow in the early 1990s, immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union. She dived into the story with a great thirst to meet Iraqis and find nascent institutions as they were first getting off the ground.

Neuffer, who had reported extensively in Iraq since the first U.S.-Iraq war in 1991, got two shocks upon arriving. The first was the overt emergence of raging politics. Before, there had been nothing but Saddam; Neuffer had futilely sought to learn about the political tastes of the population. Before the U.S. invasion, officials in Washington had told her they were looking for “an Iraqi Hamid Karzai,” that is, an authority figure friendly to the Americans who still had the credibility to ascend to the leadership. The experts looked hard and deep among the ranks of known exiled politicians, but failed to canvass the clergy, the Ba’ath Party, and the exiles who still lived in the Middle East, quietly raising money in Tehran, Damascus, Beirut and Amman. All these operatives opened offices and revealed themselves in the span of a few short weeks in April 2003. No longer terrorized by Saddam’s intelligence services, suddenly everyone had a political opinion. Political parties hung banners on recruitment offices across Baghdad, and the secular populace was flocking to the mosques, openly trumpeting their allegiance as Shi’ites or Sunnis.

Her second shock came from Sa’ad al-Azawi, the man she completely trusted as a guide and a friend. Saddam’s Ministry of Information had tightly choreographed the movements of foreign journalists, but Sa’ad had been willing to bend the rules. He’d taken Elizabeth to meet Iraqis in their homes, without permission from the official minders. He’d expressed his own discontent with life in Ba’athist Iraq, signaling that he wasn’t a true believer in Saddam’s rule. Before the war he had stockpiled supplies for the Globe at Elizabeth’s request, including the generator. He had been generous with his time and taken risks to help Elizabeth do her job.

Now, after this latest war, Elizabeth couldn’t recognize Sa’ad’s brusque rage, his blossoming greed, and his newfound faith. As soon as she arrived, Sa’ad asked her for thousands of dollars as a reward for not decamping to the competition when the foreign press corps descended on Baghdad. He demanded that she hire only his relatives, and pay them through him. When Elizabeth balked, Sa’ad sulked. He told Anne he was a Shi’ite — another surprise for Elizabeth, who knew him as Sunni. He never used to pray during the years she had known him.

He was a man at a moment of transition, undergoing a process in tandem with most of his neighbors and fellow countrymen. And at that moment, people are hard to recognize, like a bolus of molten glass just before it’s blown into a shape. Sa’ad was Sunni, he was Shi’ite, but more than anything else he was Iraqi: a survivor, mutable, adaptive, sensitive to changes in the breeze.

He might have adopted religion, but he didn’t let that get in the way of other new things he wanted to try. We were busy, but he insisted every day that we stop for lunch at the most expensive restaurants. At those which served alcohol he drank cold beer with lunch — an indulgence that not only seemed obscene in a city reeling from war and steeped in death, but a luxury of time I couldn’t afford when, already exhausted, we were working 16-hour days filing news stories, features and photo packages in a constant stream.

On Thursday, April 17 — eight or nine days after the heaviest fighting in central Baghdad — we sped down to the ancient ruins of Babylon to see whether the antiquities were guarded. Sa’ad drove like a demon on the highway, 100 miles per hour over roads rutted by tank treads and explosives. I begged him to slow down, ordered him to slow down. “Your driving will get us killed!” I screamed. I really thought it would. Sa’ad al-Azawi refused to slow down; he chose to make it an issue of pride.

Past the city of Hilla, on the plains beside the Euphrates River, we came to the site of one of the ancient world’s great wonders, the hanging gardens of Babylon, perhaps the birthplace of writing. Now a barren parking lot and a concrete arch welcomed visitors to a spot unlikely to hold anything of beauty or wonder.

We found the museum sacked, archaeological records and slides strewn across a parking lot, and no one monitoring the site. A looter’s heaven. A few old tourist guides loitered around, offering their services. We climbed atop the famous lion sculpture, posing for photographs. A Blackhawk helicopter flew low over the temple walls reconstructed by Saddam Hussein. Babylon symbolized Iraq’s awesome cultural heritage, the birthplace of agriculture and writing, the fertile land between two rivers that spawned civilization. Saddam understood Babylon’s magnetic pull for Iraqis, similar to that of the Parthenon for Greeks. Bricks inscribed with Saddam’s name accented the reconstructed walls of the ancient city, an attempt to link Saddam’s secular Arab Ba’athist Republic to the most hallowed pre-Islamic history of Arabia. It depressed me to see such a symbol of Iraqi history and culture trashed and abandoned — almost more poignant than the looting of the Archaeological Museum in Baghdad.

If to me Babylon bereft was a despondent sign of America’s failure to treat its new occupied zone with honor, for Sa’ad al-Azawi the state of disorder in this ancient place was positively humiliating. He ceased his usual angry patter and gazed with generalized hatred at his surroundings, and at us. On the way home he drove with abandon, propelling the car with such focused speed that it felt barely connected to the road by gravity. All three terrified passengers, Essdras, Rebecca and I, rode in silence, mindful of the simmering rage in our driver’s eyes. I vowed never to enter the man’s car again.

Like so many common-sense decisions made in a war zone, it wasn’t a vow I could keep. In a time of flux, nearly everyone overrules their better judgment to fulfill some immediate need — a travel visa, a safe house on the road, an important interview, a hot meal, news of a missing relative.

6.

Upon our return to Baghdad, we heard a crowd had gathered at the Ministry of Information, or rather, its ruins. It was in Karkh, right up the boulevard from the Assassin’s Gate. In front of the ministry was a park, a grassy, palm-lined square in a government quarter delineated by wide avenues, stiff statues, and grassy lawns watered by sprinklers. Everything was dissonant, though. This was the building where Sa’ad had come to get his highly-paid work driving foreign journalists during Saddam’s rule, where creepy intelligence officials browbeat reporters, revoking visas at will, determining on a whim what could and could not be said about Saddam’s Iraq.

Red Crescent workers were exhuming bodies from the park. A major battle had been fought here during the first week of April, it was said in the crowd; American infantry soldiers versus Saddam’s Fedayeen, the passionate young militiamen, many of them foreign volunteers paid $600 in cash for their fervor, choosing near-certain death in a last stand against the foreign invader. Most of them had sent their signing bonuses home before joining the fight. In Basra, I had fished the receipt for the cash payment from the breast pocket of a dead Syrian Fedayeen fighter.

In the park, the Iraqi fighters had built an old-fashioned World War I-style earthworks. Meter-deep ditches and meter-high berms meandered through a park only the size of two city blocks. It looked like a mini-golf version of trench warfare. At the end of the fight, someone had thrown the bodies of the Iraqi fighters into the trench and bulldozed over them. Now the Red Crescent had dug away the earth and was carrying the rotting bodies away one by one for proper burial. The stench was so great the Red Crescent was passing out surgical masks to the onlookers. Some of the fighters looked as if they had been buried where they had died in action — fallen face forward, a machine gun or grenade launcher still clutched in hand. All the dead were young men, wearing the headbands of the Fedayeen. Craters of rocket-propelled grenades and bullets were stacked beside them in the trench.

An outraged man wanted to talk to me, the foreign reporter. “Do you see what the Americans have done here? They have slaughtered innocent civilians! Look: men, women, children, no fighters here. Is this liberation?”

In three weeks of war I’d already seen plenty of carnage, including countless dead civilians. Here, though, was clearly a battleground, where combatants had met and perished. These specific facts were immaterial to the man in his immaculate rage: voice raised but controlled, anger expressed in singsong crescendo, hair and mustache neatly combed, shirt tucked in, no excess sweat or emotion. He was making a speech about a greater truth, the details of objective reality be damned. If he had spoken directly, he might have said: “I don’t want the Americans here and I loathe all this death and destruction. I hate whoever visited it upon us, even if I hated Saddam as well.” But he wasn’t interested in betraying emotion openly. Nor, it turns out, was he interested in the actual people who had died on this square, and whose bodies were being dragged out of the pit beside us. He wanted to deliver a message to me, in a guise soon to become familiar to me: a cloak of righteousness, denial of reality, and literal lies, all in service of expressing an emotion that heralded an undeniable truth. The Americans had killed countless civilians and now they were occupying the country. That was the source of his outrage. So what if right here, in this particular place, Americans had killed Fedayeen soldiers in combat?

Then, so early in my time in Iraq, I couldn’t understand why was this man was describing a false reality in order to make a genuine point. A hundred meters away on the same street was a burnt car with a dead family inside. Why make his argument by identifying gun-toting Fedayeen boys as women and children? But my mistake was that I was still thinking too literally, not realizing that the war had created a new, liquid realm, which empowered everyone to name things anew. This state of mind was the key to the sectarian opening; anger and emotion pave the way to an alternate reality, in which literal truth doesn’t count, and then the sluice opens, ready to accept the torrential washing waves of the sect.

“Don’t these men look like fighters to you?” I asked. “What are these guns doing here, these trenches?”

“No, these are women and children,” he said, then shrugged and walked away from me. He wouldn’t give me his name.

There outside of the Ministry of Information, the still-recognizable cityscape played host to a mini-drama of war, or post-war, or pre-the-next-war. The boulevard was clear, and the row of riverfront villas across from the Ministry was fully intact, though pockmarked from shrapnel. One man had found a stray camel in the city streets and had brought it home. The beast stood in the front yard, watching the pandemonium in the park. “Why the camel?” I asked. The lady of the house explained: Her husband had gone a bit crazy during the bombing, seeing too many people die and powerless to help them. When he found the camel in the street, he brought it home, even though, she said, they barely had enough food and money to take care of themselves. For the man, it was no question: He had to help the camel, because he could. He didn’t talk to us, or to his family; he just stood in the yard, looking impassively at them, at the camel, at the crowd outside his gate.

Sa’ad al-Azawi disappeared. We found him an hour later. He said he’d been looking for us the whole time, which was hard to believe because the area we were in was so small. He wouldn’t say where he’d gone, or why he was so angry.

7.

As April 2003 wore on, Sa’ad would do his duty by the Globe, but increasingly, he would do it gracelessly. Neuffer was wary of Sa’ad’s new ego, but with the country now so unfamiliar, she relied on him to help her set up a full-strength bureau. His temper unsettled her enough that she started looking for an office manager, someone to serve as a counterweight to Sa’ad. But for the time being, she still trusted him, and acceded reluctantly to his will, hiring the drivers and extra translators he presented. He brought on board a coterie of relatives whose old jobs had suddenly vanished. I ventured into the city with a succession of drivers disgusted that they had been reduced to working for $50 a day chauffering foreigners: One was a doctor, another had a wedding photography studio, and a third styled himself a fighter pilot. A coquettish young student of English joined the bureau as a translator, although she was reluctant to work too closely with men. The nepotism was a classic case of war zone expediency: not necessarily smart, but the path of least resistance.

Sa’ad had already denounced my Lebanese translator to me, not coincidentally just after Rebecca had called to our attention that Sa’ad was taking a cut of the salaries we were paying his relatives.

“I don’t like Rebecca,” he declared. “You should not work with her. She is no good.”

“Why?” I asked.

“I cannot tell you, but you must trust me,” Sa’ad replied, with a conspiratorial look. “You must not work with her.”

“Why?” I insisted. “Can you give me any reason?”

Of course he had none, but he wouldn’t back down. “You don’t trust me?”

Mostly he worked with Elizabeth, but occasionally we still had the privilege of his seething services. While cruising one neighborhood, he chatted with some teenage men and then excitedly hustled Essdras and me into an underground bomb shelter. It was filled with acrid smoke from a fresh looter’s fire. (Why the hell do hawasim set aflame the shoe boxes they leave behind? A mystery of human nature.) We got lost and briefly contemplated suffocating to death. After we found our way out, Sa’ad defended his judgment: “They told me there were weapons of mass destruction in there!” he explained. “It would have been great for your story.”

Sa’ad al-Azawi was no more or less greedy than the other Information Ministry alumni who had parlayed their tainted but familiar relationships with the foreign press corps into office manager posts, ripe with opportunities to hand out patronage jobs, collect kickbacks, and skim money off the war-bloated news budgets. Sure, he was theatrical, he liked cash, and he made too much of a production of every gesture of generosity that otherwise would have engendered affection. But he clearly cared about Elizabeth, and he worked hard, taking risks and initiative in a society that had notably punished creative and entrepreneurial behavior. In those confusing yet heady weeks, he lurked around the Hamra, trying to preside over what he hoped would be a lucrative business empire at the service of The Boston Globe. He didn’t want to be a driver, no, he wanted to follow the lead of his old Ministry peers.

While he was a bullshit artist of the first caliber, Sa’ad was also delightfully specific, tangible, real. His loyalty had been bought through a combination of concern, gifts, phone calls, help, money and trust; he was always offering it for sale to other prospective high bidders.

I went away to Karbala for a few days. When I returned, Elizabeth told me she had fought with Sa’ad when it came time to settle the bill for his first days of work after the war. Elizabeth had refused some of his more egregious terms, so Sa’ad went looking for alternate jobs to use as leverage. His old contacts at other newspapers were wise to the game, and put off by his manic demeanor, and refused to make him offers. Sa’ad was now driving like a teenage drag racer, and praying five times a day.

On the last Friday in April I said goodbye to Anne before dawn, and Essdras, Rebecca and I piled into our rented Pajero for the trip back to Kuwait City. Sa’ad al-Azawi, in his BMW, led us out of the urban labyrinth to the drawbridge on the Kut highway. He hugged me tightly. “You are my brother,” he murmured. A pack of cigarettes strategically dispensed to the American soldiers at the riverbank got us to the front of the line for the one-lane bridge across the Tigris. By afternoon we were at the Kuwaiti border, subjected to hours of nonsensical bureaucracy (“Are you bringing alcohol? How come you have no exit stamp from Kuwait?”). That night we dined in a ridiculous restaurant shaped like a schooner at the SAS Radisson. The next day, home.

I knew I would return to Iraq soon. The day after Anne returned, however, brought horrific news. There had been a car crash, a wreck somewhere north of Baghdad. The details were fuzzy at first. We frantically called other reporters at the Hamra, Globe reporters who had replaced us in Baghdad, and Rebecca, who had stayed on as Elizabeth’s office manager. Slowly the details came in. Elizabeth was gravely injured. She had been driving back from Tikrit with her translator Walid, a gentle Republican Guard veteran whose wife was pregnant with their first child. Sa’ad al-Azawi was driving.

According to Sa’ad’s account afterwards, Walid was napping in the passenger seat, and Elizabeth was deep asleep in the back. Sometime in the early hours of dawn, Sa’ad lost control of his BMW at the great yawning turn where the six-lane divided highway bypasses Samarra. The car skidded onto the side of the road. The guardrail smashed through the engine block and went straight through Walid and Elizabeth. Sa’ad somehow emerged unscathed. Elizabeth, we learned, had died immediately. Walid was less fortunate; he apparently walked in circles trying to speak before finally collapsing.

There were lots of gruesome logistical details. Her partner, my friend and editor Peter Canellos, was trying to figure out how to get her body back home, with help from friends in the U.S. military and journalists in Baghdad. Everyone was trying to piece together what happened: Was the accident somehow war-related? Had the military caused it? Another driver? Sa’ad al-Azawi’s recklessness? Was there shrapnel in the road? And then there was the raw grief — for Elizabeth herself, for Peter, and for the shattered sense of invincibility that had somehow survived the first two months of war.

The unreality of all the killing of the last month suddenly dissolved. In all that time, I hadn’t cried once; there was too much to process, too much to write, far too much pain to hold. With Neuffer’s death, it all cracked open. My sense of grief paralleled in a small but tangible way the loss that had left almost all Iraqis raw: a pain at once personal and public, an individual death that had somehow political dimensions, since it would not have occurred were it not for the circumstances of the war.

It became quickly clear from all accounts that Sa’ad al-Azawi was to blame for the crash. The Globe fired him. Meanwhile, Walid’s family was negotiating with the Azawi clan over the fassil — the traditional compensation paid by the guilty party in the event of a crime, injury, or death. Sa’ad, however, wanted no responsibility. He had taken to harassing the Globe staff at the Hamra every day, demanding cash to replace the totaled car.

One afternoon in my office in the Boston Federal Court basement, I picked up the phone and was stunned to hear Sa’ad al-Azawi’s voice on the other end of the line, tinny and distant, calling from a Thuraya satellite phone. I had heard about his abominable behavior after Elizabeth’s death, but I gave him the benefit of the doubt.

“Sa’ad,” I shouted into the phone. “How are you doing? I’m so sorry about what happened to Elizabeth and Walid.”

With no preamble and no words of sympathy, rote or sincere, he launched his attack. “The Boston Globe cannot punish me. You are my only friend in Boston, you must tell them. They are responsible. I must pay my brother for the car. Bostonglobe owes me money for the car. Six thousand dollars! Six thousand! Where am I supposed to get the money to pay my brother? The car is destroyed because of Bostonglobe, I am working for Boston when car is destroyed. I would not drive to north unless Bostonglobe asks me to.”

I was shocked. I couldn’t believe this man had lost touch so drastically with his humanity and his manners, no matter how impetuous and prone to rage he had seemed when I first met him. If he didn’t actually feel remorse or sadness for the two deaths he had caused, I imagined he would at least be able to feign the emotion. But no: The world was out to screw him, and he wasn’t going to let it happen. I silently weathered his barrage of angry words, at first too stunned to react.

“You tell Boston I will have the best lawyer in Iraq and I will sue them if they don’t give me the money immediately!” Sa’ad was saying. Something about the simultaneous venality and absurdity of the threat knocked me out of my stupor.

“Have you gone crazy?” I interrupted, my voice hoarse, shaky and faint, the way it gets when I’m on the verge of tears or a rage episode of my own. “Don’t you have anything to say about Elizabeth, about Walid? Are you sad? Are you sorry? What’s happened to you? Two people are dead and you want only to talk about money?” He said nothing, so I continued. “As for suing, just go ahead. Please. Sue in Iraqi court and see how much they’ll make you pay, since you’re the one at fault. And for your own good, stop threatening people at the Hamra. You’ll never work for another journalist again, and if you keep showing your face at the Hamra and threatening reporters, you could find yourself facing consequences you can’t imagine.”

Only then did he backtrack, apologizing vaguely, mumbling nonsense about his sadness and sense of loss, how sorry he was; the line dropped, and I was glad not to hear his voice anymore. I couldn’t blame him for the two deaths — well I could, a little, because he drove like a maniac, but he certainly didn’t intend to kill his passengers — but I held him responsible for his behavior afterward, which reeked of cowardice, self-interest, greed, and a kind of root selfishness that I could hardly understand.

The reporters still in Baghdad were frightened of Sa’ad al-Azawi’s erratic behavior. With old power structures gone and police non-existent, everyone possessed some vague, ominous power, some reserve of the old laws of tribal justice and power. Sa’ad might have been playing the Shi’ite card, but he also came from a tribe well versed in shows of force and violent confrontation. A one-time regime thug or spook could reinvent himself as a Western media translator; a Ba’athist could come back as a devout Shi’ite clerical aide; a Westernized secular man could reinvent himself as a criminal or a resistance fighter. In fact, many men and women could and did manage all these transformations at once. Sa’ad al-Azawi loitered outside the Hamra, demanding money, and the reporters staying there worried that in short order if they didn’t pay he would sic thugs on them, people who could cause harm. Ultimately, he backed down.

8.

I returned to Baghdad in August. On my second day back, Sa’ad learned I was there and waited for me at the back gate of the parking lot in the afternoon when I returned from reporting. He looked gaunt and pale, his face far skinnier than I remembered.

I trembled as soon as I saw him, with an irrational mix of rage and fear. I was afraid of what he might say, or ask me to do, or make me want to do to him. As soon as he spoke, I realized my animal instinct was misplaced. Sa’ad had a new tack: contrition. It was almost believable. The first thing he did was hug me, desperately. He felt bony in my arms, wasted away in the three months since I’d last seen him. “Look,” he said, taking out his wallet. He showed me an ID card of Elizabeth’s that he’d kept. “I think about Elizabeth every day. I have changed my name. I have taken away an ‘a.’ My name is now Sad, not Sa’ad. I’m sorry.”

In a land where militants grooved to Boyzone and had Hello Kitty in their clubhouses, his words were only as hokey as the next English-speaker’s, if he meant them. I had no reason yet to believe that he did. He looked so fragile though, his once-angry posture now deflated to a slouch, that I couldn’t summon my own anger.

“I’m sorry too,” I said. We stood close, holding each other’s forearms. “I hope you’re okay,” I added.

“You must forgive me,” Sa’ad said.

“It’s not for me to forgive,” I said. “I’m not the one you wronged. If it makes you feel any better, though, I forgive you for any harm you’ve caused me. But I can’t help you.”

“I need to work again,” Sa’ad pleaded. “I want my job back. Please. Or help me get a job with another newspaper.”

I was too immersed in the war, too raw, too damaged to credit Sa’ad al-Azawi for the limits of his agency. He was responsible for the deaths of Elizabeth and Walid, but he hadn’t murdered them. He had shirked his responsibility and for a time had gone mad, but now his paroxysm had passed and he was carrying the chronic form of his condition. In our final encounter, it was I who failed to take responsibility and acknowledge that we were bound, and owed each other things. I knew that he had frightened me, and frightened me still, that he had nakedly pursued money and authority, and that already once he had lost hold of himself in that first phase of Iraq’s structural failure. He had lost hold of himself so wholly that he had surrendered to the tunnel vision of impulse and insulted pride.

“I’m sorry about what happened,” I repeated. I meant that I was sorry about everything that had happened, starting with the destruction of Sa’ad’s world in the war and the way he had pissed on everybody around him and ending with the pointless, avoidable deaths of Elizabeth and Walid. I was sorry that I no longer wanted to know this man, who not long ago had been so connected to Elizabeth, and who had promised to accompany me on Iraq’s journey across the Styx to whatever was coming next. I was sorry that he had failed, even though he had been under cataclysmic pressure.

Symbols of both destruction and transformation littered Iraq like the red dust from the spring sandstorms. We were learning about the first phase of structural failure, like engineers testing the limits of the materials they had created, but our lab was a nation and our materials ourselves, a society, and a web of human institutions. We knew this grisly phase was but an introduction to the failures and reinventions to come, but that foreknowledge made few of us any wiser. For the time being we were still stupefied by our inquiry into wartime physics. How long does a dead body bake in the sun until it explodes? What shape does a family sedan take after it burns, melts, and cools with the family inside? How long do half-destroyed buildings remain standing? What’s the boiling point of a man’s identity? What happens to those traces of sect, tribe, and politics when the state that suppressed them by fiat burns away in a flash?

Sa’ad al-Azawi and I would navigate Iraq’s dissolution on parallel but unconnected paths. “Please don’t come to see me again,” I said, wan and tense from the effort to control the emotions that would take me years to understand. “Good-bye.”

“Good-bye,” said Sa’ad, crying freely, but suddenly looking more relaxed than I’d ever seen him. He never contacted me again. Years later I heard he had left Iraq too. He’d taken Elizabeth’s nickname as his email address.

—

—

Thanassis Cambanis’ first book, A Privilege to Die: Inside Hezbollah’s Legions and Their Endless War Against Israel will be published by Free Press in September. He served as Baghdad and Middle East bureau chief for The Boston Globe, and writes about the Middle East and the Arab world for The New York Times, The Boston Globe, Global Post and other publications. He teaches at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs in New York, where he lives with his wife and son.