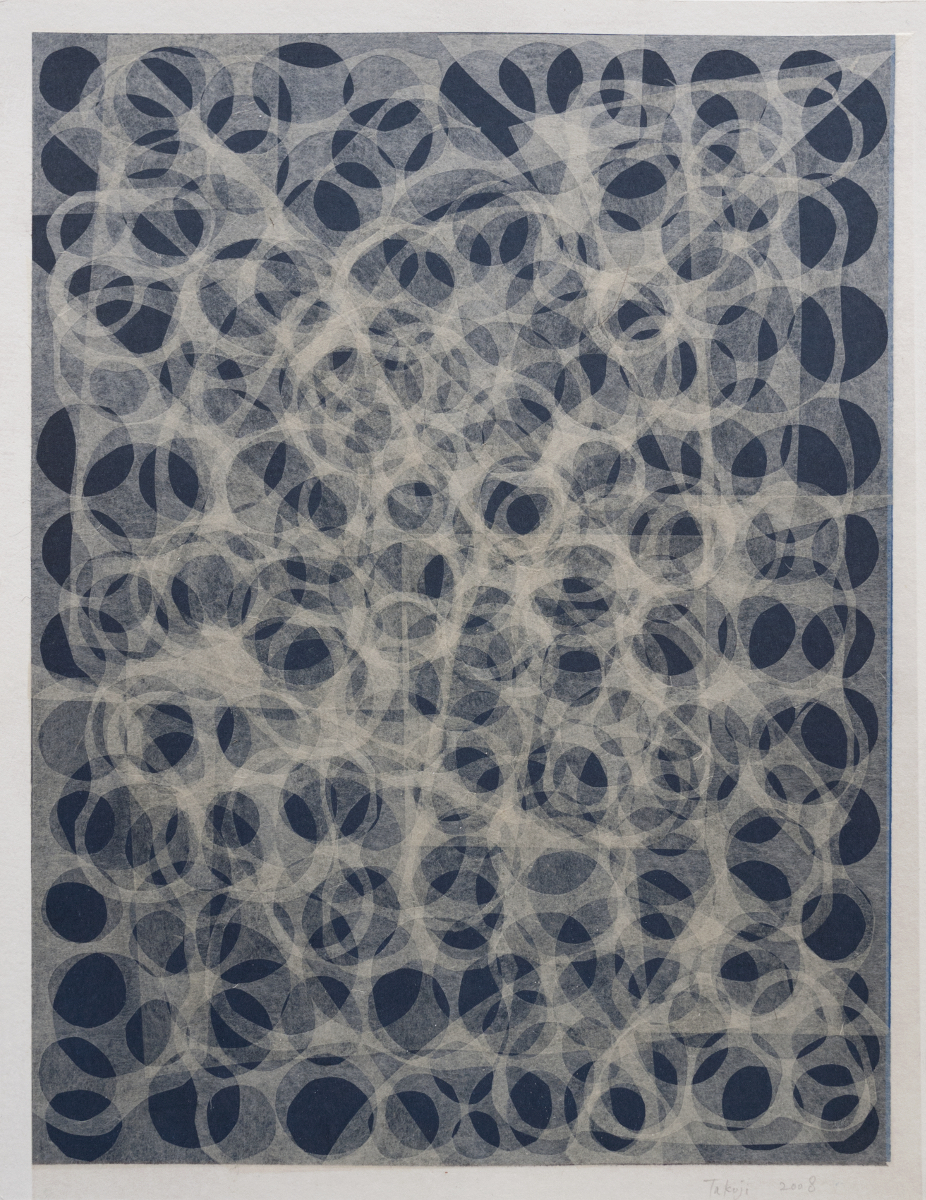

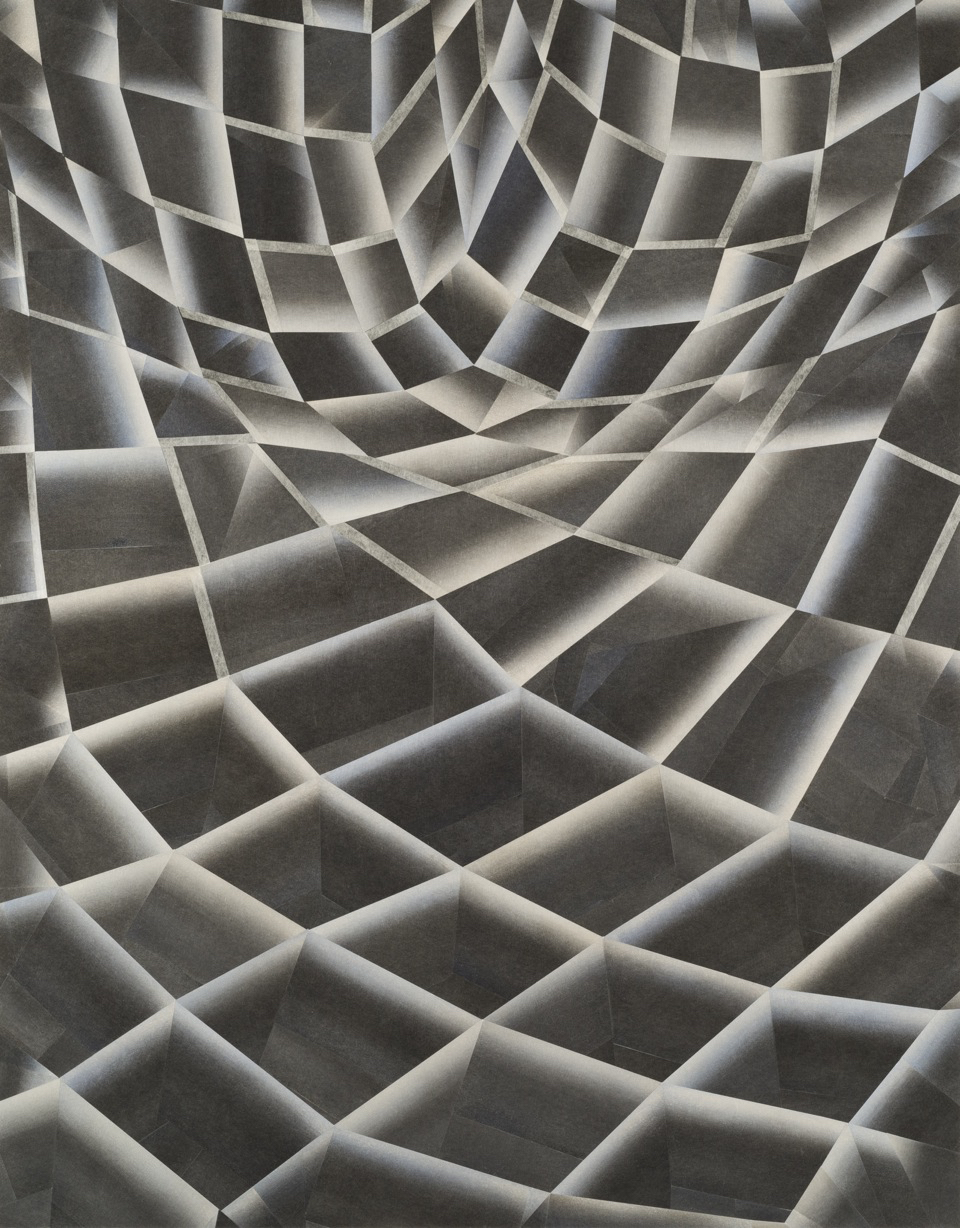

Negative Circle, 2008, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 12 3/4 x 9 7/8 inches. Image courtesy of Owen James Gallery.

In the spring of 2015, artist and printmaker Takuji Hamanaka taught an introductory workshop in Japanese woodblock printmaking at Penland School of Crafts in North Carolina. At Length‘s art editor-at-large, Elaine Bleakney, was a student in the workshop, and followed-up the experience by corresponding with Hamanaka about his painstaking inventions in process, including an extracurricular use of Japanese Gampi paper–an extremely light tissue familiar to printmakers.

At Length

I’m curious about your recent series of Gampi paper collages that alter the traditional Japanese woodblock printmaking method you have mastered. What inspired these works?

Takuji Hamanaka

It started out by a mess my mother made. In my parent’s apartment where I stay whenever I come back to Japan, there is shoji screen facing east. In the morning when the sun hits the paper on the screen, light transmits through paper, brightening the room without exposing what’s in the room to the outside.

One visit, I found a repair on the screen–a rather common occurrence you would find on a shoji screen. It turned out that my mother had broken a hole through the paper when she was vacuuming the floor. She had cut a small round piece of paper and glued it to hide the puncture. It’s something we would have seen much more back in the days when there were children in the household; you can imagine how fun it could be for a child to poke through paper with a stick or a finger. This thought was inspiring for me, maybe because I have spent many years now in a foreign land and I might have forgotten one of those typical images of daily life back home.

Once I came back to Brooklyn, I wondered if it would be possible to capture the effect I saw on my mother’s repaired screen. I started using a couple of different Japanese papers and experimented with paper-on-paper collage. They looked interesting but since I used plain paper there was no color and it was hard to see the layers unless I placed the collage by the window. After a couple of experiments with different papers and mixing this up with woodcut, I started using Gampi paper. I have known Gampi as used in the Chine-collé technique in etching and lithography. But I wanted my application of Gampi to be quite different from the way it is usually done.

Traditionally, Gampi is used at the receiving end of printing: its surface is fine and smooth so that an image on a plate or stone can be transferred to it much better than other heavier papers. What I do is use Gampi as a more active main component in image making. I cut a large number of papers, sometimes hundreds of them in different shapes, and repeatedly paste them on the woodcut.

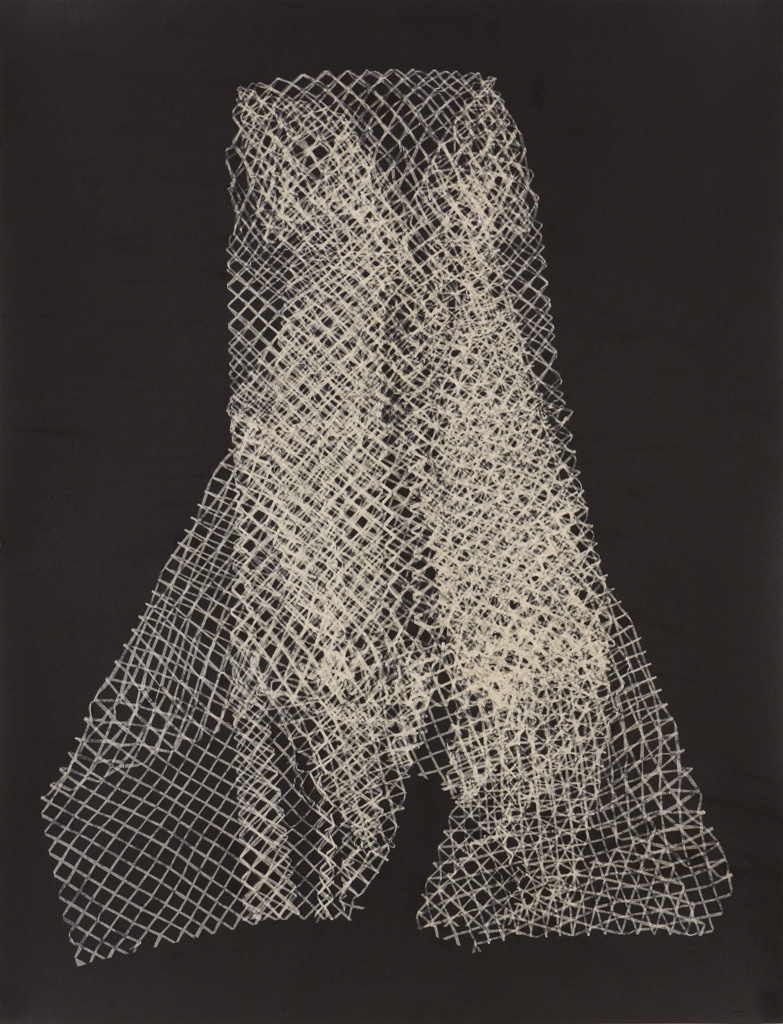

Night, 2012, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 30 3/8 x 23 3/8 inches

TH

I like the translucency of Gampi paper and the effect I can achieve by layering. Once many layers of paper are pasted on the woodcut it attains a somewhat contradictory visual effect: in one sense it appears to be so flat because of nature of paper yet if you take microscopic point of view there are mountains and valleys of paper. It’s as if you’re looking down into clean and deep water, seeing from the surface to the bottom, capturing the distance between the peak and the depth. I also feel that repeatedly pasting paper after paper is like making a time recording device: time spent on one particular piece is visible and can be returned to even at the end of the process.

For the last several years I have been thinking about characteristic expressions or materials in printmaking and using them in an unconventional context or a context that I haven’t tried before. My use of Gampi is one example of this. Also, I exclude act of cutting wood, except for a base-color woodcut on which I build layers of shape.

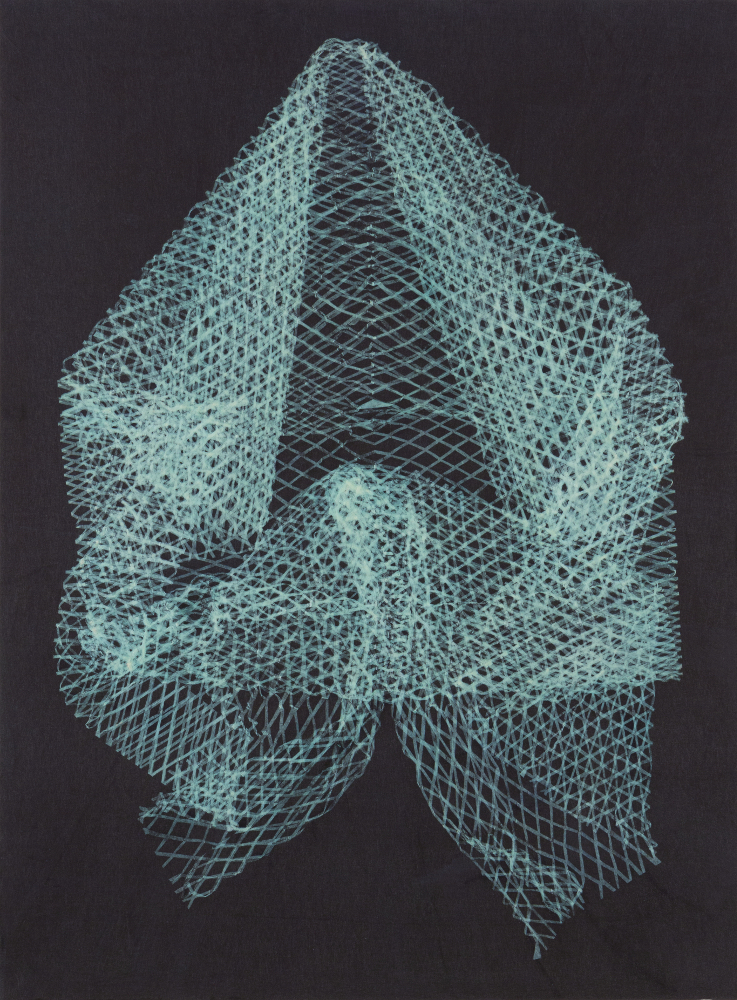

Quiet Person, 2013, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 26 x 20 inches

AL

How long does one of the Gampi collages take? Do you find that–embarking on a technique with the paper that is unconventional–your errors also feel unconventional or surprising?

TH

Collage works takes so much time to complete. The paper itself is so thin and light that it requires extra care to handle/cut it in the shape I like, and in some of these works I cut hundreds of different-shaped papers, individually pasting them in one work.

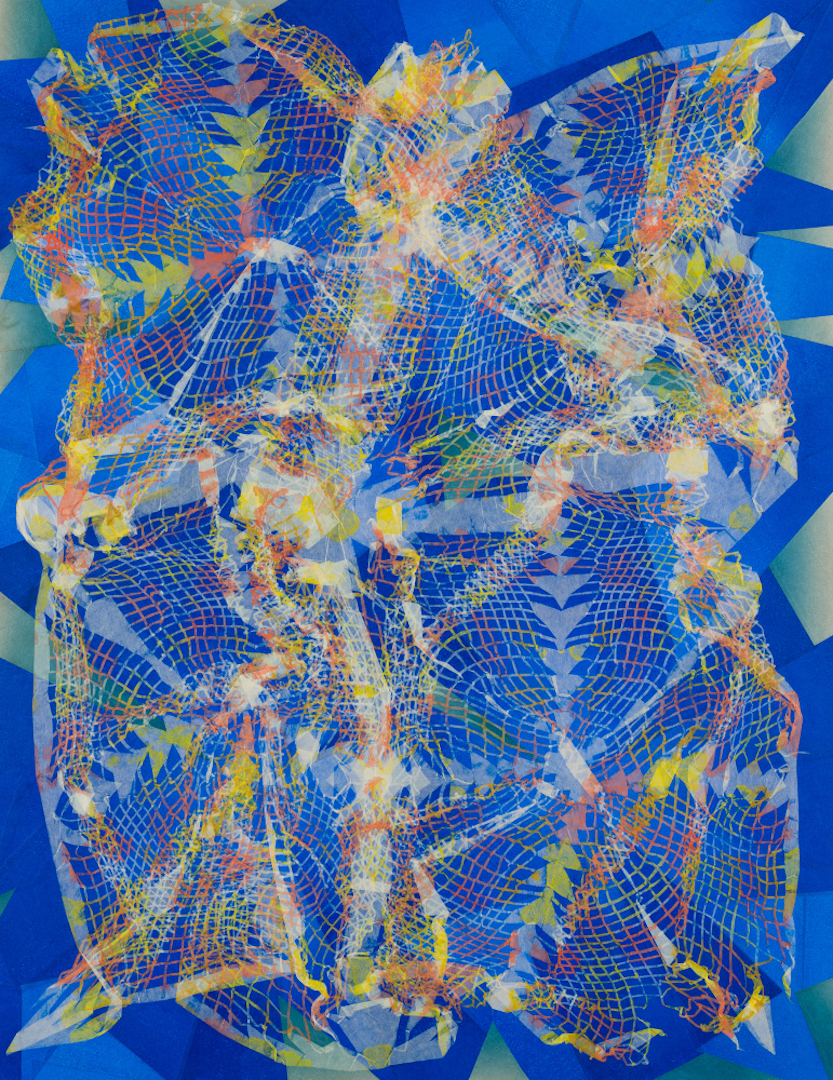

Sometimes I found that when I applied wet Gampi to print, it didn’t adhere in clean way and looked like bad wrinkled paper. This really disturbed me. I put aside those mistakes. But after a while I looked back and found potential to explore some other direction in my works. How what disturbed me became something interesting, I don’t know–but the more I looked at them the more I started to see differently. This is how I started cutting many grids on a sheet of Gampi, making a sort of paper lace and fold like Veil [shown below]. Error would happen often in a way that could be inspiring. Of course sometimes an error was just error and pissed me off!

Veil, 2013, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 26 x 20 inches

AL

The scene you speak of–your mother repairing the shoji screen–I’m wondering if you’ve told her that it inspired your current work?

TH

After I made a good chunk of collage works I did tell my mother how I got inspiration in the first place and she demanded some credit, only laughingly.

AL

Does it surprise you, looking back and through to the place where you have arrived in your work?

TH

I often think about using the characteristic expressions and materials of printmaking in different contexts. I guess you could call it ‘transplanting’ or ‘displacement.’ Putting familiar elements in unfamiliar places creates different meanings and that simple act really intrigues me.

AL

Did these acts of displacement feel like acts of bravado, at first, considering your years of formal training in traditional Japanese woodblock printmaking?

TH

It is true that I was trained in a very traditional printmaking style [at the Adachi Woodcut Print Studio in Tokyo] where they force you to you adhere to a set of values in visual sense, and the ways things should be done.

I appreciated that visual sense and respected it very much. I still do. But even when I was an apprentice I was aware how living in very restricted environment (traditional printmaking) affects your way of thinking. In a way it feels like a complete world where the rule is clear and the standard is set and you only need to achieve that, no more than that. That alone is not an easy task. But the limit is set. For me, making art is to break [a limit] and displacement helps me realize this.

In traditional printmaking, a clean beautiful finished surface of print is critical and you aim to achieve that. In contrast, I felt an urge to curve and mess up lines using a v-shaped gouge to make a print complete. This was against what I acquired at the shop and it was a very interesting moment for me. I understand to some people this might be nothing but for me it was a good step forward to making interesting works.

AL

Did your work on woodblock print editions for artists like Sol Lewitt and others encourage you in a more experimental direction?

TH

Having the opportunity to work on a Sol Lewitt print project [at Watanabe Studio in Brooklyn in the early 1990s] had educational meaning to me. I did not have much of a personal interaction with Lewitt but he was a very generous person. I not only looked through what he had done, but I also began looking at artists from the 1960s and 70s. The studio I worked for had lots of Lewitt books and also old editions of Artforum. I rediscovered many great works made by various artists then.

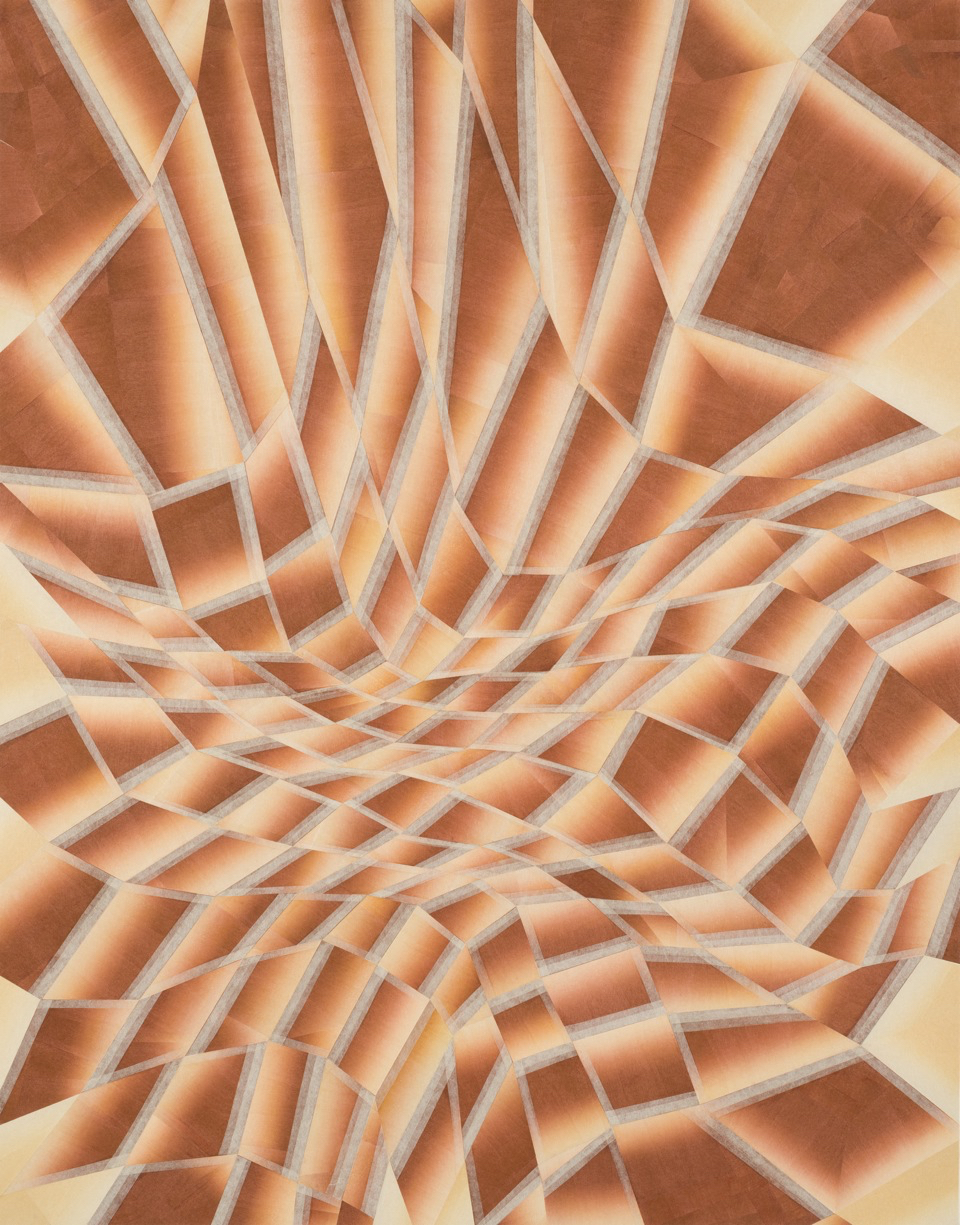

Whirlwind, 2015, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 32 x 25 inches

AL

We haven’t talked about your actual displacement–from Japan to living and working in New York City. Do you feel, looking at some of your recent work, that living in a large foreign city is something expressed in your works? In your prints Night and Negative Circle for example, I wonder if the energy in these patterns have any connection to living in a place where space is compressed or even claustrophobic at times.

TH

I have never thought about making a connection between my works and living in city. Do some of my works look urban to you, I wonder.

I am aware that it is good thing for me to stay away from NYC from time to time. Wherever you live I think it’s nice to step outside of your familiar environment and see it from another point of view, if you can.

One thing I can say I like about living in a big city is that I can be anonymous. This gives me a sense of freedom.

Shattering Echo, 2015, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 32 x 25 inches

AL

How do you experience the city geography? Do you walk often?

TH

I’ve enjoyed walking since I was young in Japan. On sunny days I used to walk to the nearest town to check out a bookstore and such. It was long walk, a little more than two hours round trip, but I enjoyed that. I did not enjoy using public transportation. I liked the private space I could maintain while walking.

I still prefer walking to riding a bicycle in my neighborhood here in Brooklyn. I like the speed of walking: no rush, not so fast.

AL

When you were young, what sorts of books did you enjoy looking at?

TH

When I was young I would go to various second-hand bookstores. I wasn’t a physically strong kid but I never seem to get tired when I was at a bookstore. I would search through piles of old book and magazines for hours. Mostly I was interested in literature and books about woodcut. I also liked the book as object, a beautiful cover design and text to read. These combined seemed to me a perfect medium.

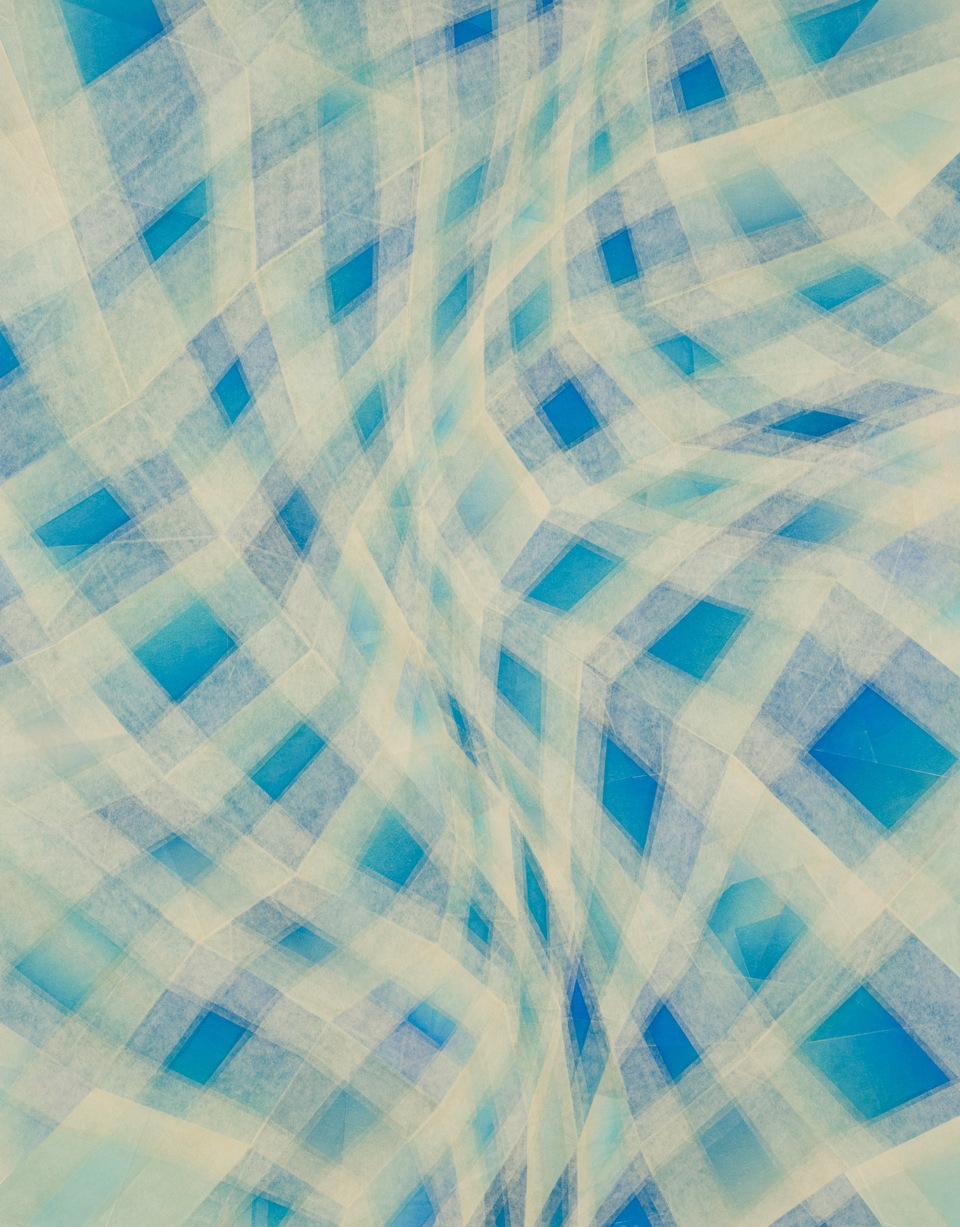

Kasutera, 2015, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 32 x 25 inches

AL

There is something about color in your newer works, the layering of color and tones, that evoke interior emotional life to me. Do you have thoughts about color and your relationship to it?

TH

There had been a time where I could only work in black and white–for a long time. Generally my relationship with color wasn’t good, it was always difficult and I tended to minimize the use of color. But my very current works and a new series of works I hope to finish in a few months will be a departure. I am quietly excited about the possibility these new works embody.

Distorted Web, 2015, Japanese woodcut with Gampi paper collage, 32 x 25 inches

Takuji Hamanaka presenting a slideshow of his work at Penland School of Crafts. Photograph by Elaine Bleakney.

Takuji Hamanaka is an artist and printmaker living in Brooklyn, New York. He apprenticed in traditional woodcut printmaking in Tokyo, Japan. In recent works he combines printmaking with collage, using extremely thin Japanese paper called Gampi. His work has been exhibited at the International Print Center, New York; Whitman College, Washington; National Academy of Fine Arts, India; and the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh, Scotland, among others. Takuji Hamanaka has received a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship, NY; KALA Art Institute Fellowship, CA and has been a resident at the MacDowell Colony, NH; Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, ME; and at Open Studios, Museum of Arts and Design, NY. He is represented by Owen James Gallery in NY.