For our latest feature, we’ve asked 50 poets to weigh in (briefly) on the long poems that interest them. To avoid spending too much time on the usual suspects, we suggested that most of our contributors focus on poems from the last 70 years.

This is the first of six installments (you can see the others here, here, here, here and here.) Scroll down or click on the links to read:

—R.T. Smith on Robert Penn Warren

—Michael Leong on Nick Montfort And Stephanie Strickland

—Dana Levin on Anne Carson

—Paisley Rekdal on Marianne Moore

—Cecily Parks on Lorine Niedecker

—John Poch on Charles Martin

—Daniel Bosch on Derek Walcott

—Spencer Reece on Adrienne Rich

—Michael Ryan on Emily Dickinson

—Sam Hamill on Thomas McGrath

—Erica Dawson on Anthony Hecht

—Robert Pinsky on George Gascoigne

R.T. SMITH ON ROBERT PENN WARREN

“Tell me a story,” says the child yearning to delay the darkness, and all the better if the story features recognizable characters and patterns, if something important is imperiled in the narrative, then rescued, and if the tale is, in the end and against expectation, soothing. In an era of so much discordant poetry built of fractured structures and anti-melodic prosody, I remember how startled I was on first encountering the shifting planes, altered pitches and bold, jigsawing parallelisms of Robert Penn Warren’s poetic sequence Audubon: A Vision. He has anticipated so many of the current free-wheeling strategies, but without sacrificing coherence and the conventions of common sense, without striving to be gnomic or difficult. And I also remember how spellbound I was with the flashes of candor from Warren’s narrating persona, who says in the final movement, “I did not know what was happening in my heart.” Forty years after the poem first found me, I am still in awe of it.

Why was the discovery of that poem so word-altering and world-altering? Operating by turns as agent of historical narrative, allegory, meditation and lyric–a song as well as a story–Audubon brought back into relevance the frontier, the haunting natures mortes of the great artist/ornithologist and my own questions about source and destiny. It serves as a powerful reminder of how the Other of the natural world, confronted deliberately, could provide direction and amplitude to the search for identity, as well as an arena for epiphany.

The poem is a benchmark, beyond Warren’s own aesthetic evolution, a guide for Americans willing to admit to shortcomings like pride, greed and pretentiousness always marbling the national virtues, for the person fleeing civilization with its (as Merwin puts it) “ruth of the lair” to risk the indigenous perils and revelations lurking in the wilderness. The poem dramatizes both Audubon’s and the author’s attempts to reconcile romantic idealism and pragmatism, to reach out and discover one’s own unclassifiable core in a realistic realm both mysterious and flat-iron factual.

The shape of the poem is not simple, yet its seven numbered parts signal to readers a design near-symphonic, if rife with elements of fugue, riff and aria, all brought to bear on questions of identity, myth, dream and compromise. In the final section of boyhood epiphany, the poet makes a plea, asks to be told a story “of great distances and starlight,” named Time, but that name unuttered, “a story of deep delight,” a phrase surely borrowed from Coleridge’s interrupted dreamer.

The glory of this poem is, in part, its boldness: by turns imagistic and elliptical, in part philosophical, it combines episode, summary and conclusion, but refuses mechanical continuity, employing tonal overlap and emotional resonance on a cosmic scale (the dawn is “God’s blood spilt”), conveying a three-dimensional feel. Yet its central episode, in which the painter/hunter is rescued from goblin-like outlaws who would slit his throat over a gold watch, is riveting in its naturalism, while offering a troubling chronicle of the inevitability of horror.

The two aspects of this poem which most haunt me are the grim story which unfolds at dark; “On the trod mire by the door crackles the night-ice already there forming” to provide the threshold of a “dark hovel /In the forest where trees have eyes,” which he (surely Warren here, through Audubon) retains from childhood. The deliberate pace, building suspense, the imagery of dim light, a one-eyed Indian, the “whish of silk” as the grotesque hostess hones her knife on a spat-upon stone, the terror and paralysis–it’s one of the great episodes in our literature.

Over the years I have concluded that Warren has led me to experience poetry as language sculpture, architecture, without sacrificing the thematic weave, satisfying patterns and echoing, reinforcing sounds, which in Understanding Poetry he had called “the tangled glitter of syllables” and which I went to the well of poetry in quest of. Once I recovered from my shock at the formal appearance of the poem, I began to learn my way around it, weaving through biography, history, metaphysics, folklore and bold invention. I had not expected any poem to quench and nourish me the way “Audubon: A Vision” had with its imprinting in my imagination a distinctly American quest accepted by a man who represented our national hardships and achievements, their romantic distractions and their roots in the understory of the forest, where power and access, beauty and apprehension are steadily negotiated. In short, Warren had made it personal in ways I could neither ignore nor deflect.

Even now, as I have learned it by heart, I find the poem coming alive inside me at moments of strong emotion, as I hear “The great geese hoot northward,” delivering that “deep delight” with, even in the resonant “first dark,” so much promise, richness, the sheer pleasures of mind and tongue.

MICHAEL LEONG ON NICK MONTFORT AND STEPHANIE STRICKLAND

O What an endlesse worke haue I in hand,

To count the seas abundant progeny

—Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queene

In terms of scope and scale, Sea and Spar Between is—according to one perspective—a modest piece of text; indeed, in their explanatory introduction entitled “how to read Sea and Spar Between,” Nick Montfort and Stephanie Strickland describe their composition as “fairly small and simple.” It is, to be precise, 502 lines long–shorter than Wallace Stevens’ “Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction” and slightly longer than T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. In a recent technical report, Montfort considers it a “medium-length” project. But the “it” to which I have been referring is not a poem per se but the JavaScript code that implements Montfort and Strickland’s online poetry generator, which is capable of producing approximately 225 trillion unique stanzas or a long poem that would require what Spenser might call “endlesse worke” to read and interpret. The code itself might be relatively short, but it offers a virtuality of poems of enormous length or, indeed, an endless, interactive poem. The output stanzas of Sea and Spar Between (whose total number is comparable to “the number of fish in the sea”) is based on particular words found in Emily Dickinson’s poetry and Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. The carefully selected “word-hoard” (which, as the authors point out, depended upon quantitative counting as well as a qualitative understanding of Dickinson’s and Melville’s rhetorical styles) includes monosyllables such as “buzz,” “pike,” and “hive,” which are combined or re-mixed into kennings (“hivehusk,” “pinkblur”) and words that are appended with the “-less” suffix (“phraseless,” “noteless”) that reflect Dickinson’s interest in negativity.

“Each stanza is indicated by two coordinates, as with latitude and longitude.

They range from 0 : 0 to 14992383 : 14992383.”

Other structures include a series of imperatives, such as “circle on,” “dash on,” “loop on,” “reel on,” and “roll on,” which I read not only as a meta-textual commentary on the potentially endless unfurling of stanzaic structures but also as an extended dialogue with the climactic and penultimate section of Walt Whitman’s “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” (a lyric in which the speaker memorably exhorts the river, waves, birds, and ships to “[f]low on,” “[f]rolic on,” “[f]ly on,” and “[c]ome on”), creating a suggestive triangulation of three of the most inimitable American writers of the nineteenth-century.

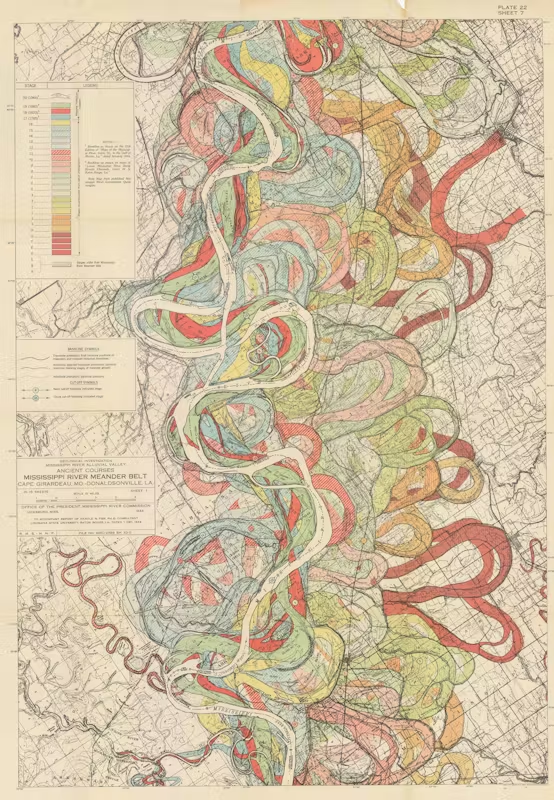

The field created by the generator is a “sea-like” expanse framed by the dimensions of the web browser, allowing the reader/user/performer to scroll vertically and horizontally through the text, simulating the effect of nautical navigation (Sea and Spar Between was first published in an electronic journal called Dear Navigator). Such an effect might be analogous to what Ezra Pound called sailing “in periplum” (the stated objective of his Cantos)—that is, apprehending the earth “not as land looks on a map / but as sea bord seen by men sailing.” Yet the sensitivity of the program is such that just a modest movement of the computer mouse or gesture on the touchpad will send the reader hurtling through the stanzas at sometimes vertiginous speeds. It is sailing “in periplum” but turbo-charged.

If Sea and Spar Between is a map-like representation, it is a dynamic one that refuses a totalizing schema. One is able to zoom out in an attempt to get a bird’s eye view (by pressing the “Z” key) but only to the limited extent that 70 whole stanzas will be visible at any given time. Contrastingly, by pressing the “A” key, one is allowed to zoom in to a much greater degree, to plunge into the blue, to delve deeper and deeper into the spaces between lines, to conduct what poet Ed Roberson might call “research at the interstice.”

These videos above dramatically demonstrate new interactive modes of reading that are now possible in our digital age. But rather than repudiating older, more established ways of reading, Sea and Spar Between asks the reader to conceive of reading in the twenty-first century as a heterogeneous activity that encompasses a variety of skills, concentrations, and demands. That reading is not a monolithic process seems obvious. Yet when it comes to approaching literary texts, reading is almost always (and not surprisingly) defined as a slow and painstaking endeavor. For example, after Oprah Winfrey chose Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon for her book club in 1996, Winfrey called Morrison and asked, “Do people tell you they have to keep going over the words sometimes?” Morrison famously responded: “That, my dear, is called reading.” More recently, Dana Gioia’s preface to the NEA’s controversial report Reading at Risk (2004) has extended this conventional wisdom in claiming that “[r]eading a book requires a degree of active attention and engagement…. By contrast, most electronic media… make fewer demands on their audiences…. Even interactive electronic media… foster shorter attention spans and accelerated gratification.” As a literary text, Sea and Spar Between is remarkable in the way it calls for not only a narrowly defined kind of “active attention” but also an “accelerated” engagement. The reader’s ability to rapidly surf across the flickering surface of the poem might be understood, along with the related on-line activities of browsing, skimming, and scanning, as the passive and impoverished type of reading that Gioia decries. But I would argue that this “speed reading,” as it were, is a crucial component to the overall appreciation of the poem. Montfort and Strickland’s readers are able to enjoy the aesthetic experience of skimming through a vast and breathtaking textual ecology just as readers of a printed codex can relish the turn of each page and the sensuous feel of the book in their hands. Surfing through the trillions of these fragmentary stanzas allows one to more fully register the poetry generator’s mathematically sublime output.

Moreover, Sea and Spar Between’s zoom function encapsulates—in a brilliantly transformed fashion—both “close reading” (hearkening back to a reading practice that started at least with I.A. Richards and progressed, most notably, through the New Critics) and what Franco Moretti has polemically called “distant reading” (a recent methodology, outlined in the essay “Conjectures on World Literature,” which involves not the careful scrutiny of particular texts but the synthesis and analysis of large sets of quantitative data in order “to focus on units that are much smaller or much larger than the text: devices, themes, tropes—or genres and systems.”) The output of Sea and Spar Between is a rich, combinatorial poem in its own right, but it also offers the productively defamiliarizing experience of reading Melville and Dickinson “at a distance,” giving us a “slant” perspective on two very familiar, canonical authors. Toggling back and forth between the close and the distant allows for exercising different scales of focus whether it be jumping from a p’s descender to an l’s ascender in the word pole (like Melville’s Ishmael hopping “from spar to spar, like a grasshopper in a May meadow”) or floating far above the stanzas in this digital sea (like one of Dickinson’s butterflies cruising “[i]n purposeless Circumference / As ‘twere a Tropic Show.”) We can say that Montfort and Strickland’s poetics privileges neither the sea nor the spar but the between.

In short, Sea and Spar Between suggests that the long poem in the digital age has to make room for shifting kinds of attention, slow and fast, near and far. If we are to ponder the fate of reading (and of reading the long poem) at the beginning of this new century, at this interstice between print and digital textual cultures, we would do no better than to explore the sublime permutations of Sea and Spar Between.

DANA LEVIN ON ANNE CARSON

Clear as an Alarm: 675 Words on Anne Carson’s The Glass Essay

Anne Carson’s thirty-six page poem The Glass Essay, from 1995’s Glass, Irony and God, turns on the most precarious of pivots: love lost. Who has not attempted such a poem, only to be repelled by melodrama, self-pity, sentimentality, cliché? “Not enough spin on it,” the speaker’s lover of five years declares on page eleven. Stunned, demolished, the speaker flees to her mother’s home on the Canadian moors, The Collected Works of Emily Bronte in tow. There, where “the April light is clear as an alarm,” where “the bare blue trees and bleached wooden sky” carve into her “with knives of light,” Carson’s speaker gets down to the work of trying to understand what has happened to her. She reads, she thinks, she walks, she has banal conversations with her mother; she says “I am not unfamiliar with this half-life” after describing Bronte inventing a Heathcliff who, in the place of a soul, has “the constant cold departure of Catherine from his nervous system.” For a poem sparked by a break-up, with the heart-slinging, fate-slapping Wuthering Heights as ur-text, the tone of The Glass Essay is thrillingly, devastatingly, deadpan.

Where then is the drama in this long poem? The drama is in perceiving and thinking, in the desire “to speak more clearly” and the cool, lacerating narratives of analysis that follow. The drama of feeling is constantly deflated or displaced. Descriptions of light, weather and landscape, quotations from Bronte, and, later, the hallucinatory appearance of the fantastic Nudes, serve as feeling-emblems; the speaker “whaches” them like a reporter at a parade. “To be a whacher is not in itself sad or happy,” Carson writes; she’s describing Bronte but it’s a key too to understanding the poem’s tonal attitude, so at odds with the excruciating pain we know, via image and quotation, the speaker is feeling (the poem is a triumph of the objective correlative):

When Law left I felt so bad I thought I would die.

This is not uncommon.

I took up the practice of meditation.

Each morning I sat on the floor in front of my sofa

and chanted bits of old Latin prayers.

De profundis clamavi ad te Domine.

Each morning a vision came to me.

Gradually I understood that these were naked glimpses of my soul.

I called them Nudes.

Nude #1. Woman alone on a hill.

She stands into the wind.

It is a hard wind slanting from the north.

Long flaps and shreds of flesh rip off the woman’s body and lift

and blow away on the wind, leaving

an exposed column of nerve and blood and muscle

calling mutely through lipless mouth.

It pains me to record this,

I am not a melodramatic person.

But soul is “hewn in a wild workshop”

as Charlotte Brontë says of Wuthering Heights.

If we had kept on with the Confessional impulse as an exploratory mode―if its central practitioners had not been felled by madness and compulsion―maybe we would have eventually gotten a poem like this out of Berryman or Plath: a poem without raging and maudlin ahoys, where Confessionalism’s essential gift―self-analysis―was given free rein to get beyond personality (Lady Lazarus! Henry!) and closer to what might be called a sense of soul. The Glass Essay deflates self-importance while at the same time completely validating the scarring nature of personal emotional experience; it also honors such scarring as a subject worthy of poetry―perhaps not the most casual thing to do in the early 1990s, as American poetry was walking away from Confessionalist bequests. The primary difference between Carson’s Nudes and Plath’s Lady Lazarus is that Carson’s speaker doesn’t take personally the emotional stripping loss compels; she recognizes it as part of the soul-hewing in the “wild workshop,” a hewing that, in the quest to “carry this clarity with me,” she endures until the last page’s last Nude, whose bones stand “silver and necessary/…the body of us all.” The poem teaches us to think through feeling; I find it immensely solacing.

PAISLEY REKDAL ON MARIANNE MOORE

Moore’s poem “The Jerboa” may best be summed up as a poetic debate about what defines versus what passes for art. In the first half of the poem, Art is either representational–in particular, mimicking the elaborate and entirely organic forms in nature, such as the pine cone, duck wing or the tail of a peacock—or manipulated, in that animals are taken out of their natural environment and forced into activities meant for human entertainment, such as the “dappled dog-/cats” used “to course antelopes,” or the baboons that perch “on the necks of giraffe to pick/ fruit.” Moore is clearly suspicious of both these kinds of art, which is everywhere slyly denigrated: from the heading of the first half of the poem itself (“Too Much”) to the sidelong glance inherent in Moore’s subjunctives and passive verb tenses (“Others could build” and “it looks like a work of art”), artistic representation is based on man’s assumed mastery over nature, as everything here is massaged, manipulated or brutally trained into pleasing use-forms for the households of nobility. Here, art is not just a product of empire, it is a way of maintaining empire itself. And how can it not be, when the art proves to be so voracious in its accumulative gaze that it becomes “a fantasy/ and a verisimilitude that were/ right to those with, everywhere,/ power over the poor”?

Such, Moore’s poem argues, is the real definition of “too much”: any art swollen with self-importance and notions of political mastery becomes, finally, an art of accretion, domination and excess. It’s tempting to extrapolate from this Moore’s possible suspicion of representational art in general, and to consider the poem’s possible critique of certain art forms today. For example, is this a problem representational or narrative art itself creates, or is it a problem that arises in the specific instance where empire meets representational art? Is representational art the “natural” choice for consumerist societies, in particular cultures busily ravaging the natural landscapes around them? Is it the expression of an empire’s faded dreams or its final death knell? Reading “The Jerboa” now, I can’t help thinking of the recent death of that famous American workhorse Thomas Kinkade, and of his kitschy, hyper-elaborate and pseudo-pastoral landscapes that were (and, I’m guessing, still are) sold in the exhaustively cultivated bucolic downtowns of places like Aspen or Solvang.

Compare this, however, with Moore’s notion of “Abundance,” the title of the second-half of her poem. Here she finally presents the jerboa of the title: a pin-thin, tidy little desert rat whose two real skills in life are a) being able to jump exceptionally well and b) being able to disappear into its environment. Leaving aside for the moment Moore’s famous introversion which might make her seem like the perfect ally for a desert rat (or vice-versa), what’s important about Moore’s imagery of the rat is how it, too, manages to encapsulate within its appearance a plenitude of other animal and natural forms. The jerboa’s head is like a bird, it has “chipmunk contours,” moves with “kangaroo speed,” and has fur on its back that’s “buff-brown like the breast of the fawn-breasted/ bower-bird.” Even the fine hairs on the tail possess a mark “fish-shaped and silvered to steel by the force/ of the large desert moon.” The jerboa becomes the art form into which dozens of other animals are contained, not by political but by natural comparison and accretion; also, implicitly, by the force of Moore’s imagination.

There’s also the issue of race to be considered. As Moore writes in the opening to her second section:

Africanus meant

The conqueror sent

From Rome. It should mean the

Untouched: the sand-brown jumping rat—free-born; and

The blacks, that choice race with an elegance

Ignored by one’s ignorance.

It’s a back-handed and also racist “compliment”—to compare Africans (and by extension African-Americans) with a desert rat as an indirect attempt to criticize America’s ignorant racial policies–but I think Moore is exploring a larger point about the problems of critiquing narrative representation, even as she makes the same mistake herself. To express ourselves to ourselves, as “The Jerboa” argues, we often have to resort to images that we create about the natural world. These are images that we worship, desire, cultivate and abuse, but they are often the only way through which we can express our more abstract longings. If an empire is obsessed with the reach of its political power, the art forms it chooses will begin to reflect the anxieties of that power, which is why the Romans seem—as Moore notes—to like “small things,” and why the words “free-born” and “freedom” reappear (and why “the blacks” would be a notable inclusion) in the poem as important descriptors. Moore is no better than the Romans she critiques in this regard: as they have made representations of peacocks and pine-cones to reflect and be dominated by their aesthetic and political interests, so too has Moore loaded down the simple jerboa with her own yearnings for the freedom she assumes that simplicity, natural skill and invisibility will provide.

Which is why I think the aesthetic divide between the “Too Much” of political art and the “Abundance” of natural or organic forms of art that “The Jerboa” proposes is ultimately a red herring. In the end, Moore can’t escape the problems of representation that she investigates as these problems are built into any language contained in narrative argument: as soon as you start to describe the world in any representational terms, you have made a stance. Language itself isn’t clean, containing—and representing–as it does both literal definitions and figurative meanings. We may applaud the simplicity of the jerboa, but the language that Moore uses to describe it is as ornate as anything the Romans contrived as toys for themselves. The question, then, that obsesses me as I read Moore’s poem—and the one which may best define my own political self-understanding—is which type of excess I want to believe passes as more naturally “artful.” It’s one reason why I return to “The Jerboa”—and Marianne Moore—so frequently: to see how my own definition of art continues to change, and to test it against Moore’s own bracing examinations.

CECILY PARKS ON LORINE NIEDECKER

Lorine Niedecker’s “Paean to Place” celebrates Blackhawk Island, Wisconsin—a periodically flooded peninsula flanked by Rock River and Lake Koshkonong—where the poet spent most of her life. The poem spans decades, beginning with an account of Niedecker’s childhood and ending with a meditation on the marginality of human life in contrast to the sometimes-cruel landscape that makes such life possible. The poem cascades through multiple pages, but its lines are almost ruthlessly short:

Fish

fowl

flood

Water lily mud

My life

In eight words, this opening stanza introduces the three most captivating aspects of Niedecker’s poem: her music half-indebted to the nursery rhyme, her trust in the chosen word to build an expansive line, and her celebration of a natural world that includes not the birds and flowers of the pastoral tradition but rather fowl (a pun on foul) and mud.

The form and content of “Paean to Place” reinforce a theme of subsistence in a place without sweetness, without brightness: “No oranges—none at hand / No marsh marigold[.]” When Niedecker remembers her father coming home with “a sack / of dandelion greens,” the reader tastes the weeds’ bitterness and feels their jagged leaves inside her mouth. Unpleasantness also characterizes Niedecker’s parents’ dissolving marriage, in which the poet’s father “Saw his wife turn / deaf // and away[.]” For the poet herself, there was: “Seven years the one /dress // for town once a week[.]” The poem celebrates not what Blackhawk Island provides but rather the thrill of living in a place where provision is scarce. Niedecker declares:

O my floating life

Do not save love

For things

Throw things

To the flood

Over the course of the poem, the act of writing reveals itself as an act of jettisoning: “Paean to Place” allows Niedecker (who was in her sixties when she wrote it) to cast accumulated adversity into the flood of time. What remains is “moonlight memory / washed of hardships[.]” By calling the poem a paean, Niedecker indicates that it is meant to communicate triumph. What triumphs is the act of thinking, which becomes inseparable from the floodscape where it takes place. The poem concludes:

the sloughs and sluices

of my mind

with the persons

on the edge

Among the anonymous persons who stand poised to be washed away by the force of the flood is Niedecker, who relinquishes herself, and the poem, to the white space after the poem’s final unpunctuated word.

JOHN POCH ON CHARLES MARTIN

There are few good poems in terza rima in English and there are perhaps even fewer good poems about the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center of September 2011. You would think that Charles Martin’s “After 9/ll” would be an impossible poem to write. It is impossibly good.

Some might not think of a 118-line poem as a “long poem,” but when you see the dearth of poems in English terza rima written with an essential and cleanly rhyming iambic pentameter, you tend to think of this kind of poem in different terms. Dante had an easier time achieving the rhyme in the vernacular Italian, for sure. The only other recent poem worth reading in English terza rima I can think of is Greg Williamson’s “On the International Date Line.” Richard Wilbur, our best living master of the iambic pentameter line, has a poem called “Terza Rima” in the form, but it is only sustained for seven lines. Who doesn’t shrink in the face of Dante’s formal achievement?

Imagine a generation of people 250 years from now who cannot remember the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Impossible? Less than 250 years ago, ten thousand captured American men died unimaginable slow and torturous deaths just off the Manhattan coast in Wallabout Bay where they were imprisoned in the holds of the ships there. When they were sufficiently dead, their bodies were thrown overboard, a few washing up on the shores where they were retrieved and could be buried properly. Martin does not try to describe this. Rather, he faces the cold fact of our having forgotten our dead: four times the number of dead from the World Trade Center attacks. Four times. Imagine forgetting this kind of human terror.

We hear the politicians cry, “We will never forget.” But we do forget. Who doesn’t want to forget terror? Oblivion is both the salve and the festering wound, the drug that soothes and at the same time destroys. By virtue of this poem’s form, like Dante’s own greatest of poems, “After 9/11” summons us back through a repetition of rhyme that lends itself to the pace of crisis, to the patient equivalent of two steps forward and one step back, to a question of how we remember or fail to do so, to our dead, to a re-orientation of our lives in order that we might be saved.

In a plain vernacular Dante would approve of, Charles Martin writes of the towers “burning”:

Together, like a secret brought to light,

Like something we’d imagined but not known,

The intersection of such speed, such height—

These towers then “unmake” (a term Dante famously used) their outlines and the scene, by virtue of an almost endless repetition on television. And then, despite our memory, the horror “Would grow familiar; deadening the ache.” “Grim repetitions,” Martin writes, and this is a result of what Time perpetrates against us. Toward the end of the poem, the anaphoric use of the words “Time” and “Against” portray our annihilation through the repetition of the moments that add up to that monster, Time, reminding us of Auden’s own repetitious “Time will say nothing but I told you so.” Time… Against… us. The ticking of the clock is hypnotic, and we must ultimately sleep. Any poem may suffer its own repetition of rhyme, of anaphora, of historical duplications, but repetitions (especially rhyme) are powerful mnemonic devices, as well.

The poem ends almost hopelessly: “Against the need of the nameless to be named / In our city built on unacknowledged bones.” For who remembers the dead of Wallabout Bay? Who had ever heard of the ones who died at the very birth of our country fiercely seeking its independence, liberty, and individual human freedoms we mostly take for granted? Not one in ten thousand you might ask on the street would have any idea. But the poem itself, this poem, signifies that while we are already in the midst of forgetting the dead of 9/11 (we hate to believe this awful truth), perhaps only poetry can restore the forgotten dead, giving these “unacknowledged bones” the power to rise up and walk. These “bones” are the final word. I am reminded of Donne’s “Death, thou shalt die.”

DANIEL BOSCH ON DEREK WALCOTT

Samuel Johnson said of Milton’s Paradise Lost, “None ever wished it longer than it is.” But every time I read the 197 lines of “The Spoiler’s Return,” and I must have read them a hundred times, I am sorry to reach the last, and I wish that Walcott had let Spoiler keep talking. (And why shouldn’t he rail on? The Spoiler tells us “I decompose, but I composing still.”)

In the context of Derek Walcott’s oeuvre, to call “The Spoiler’s Return” a long poem is a bit perverse. The cast net comes back alive with such big, beautiful poems as “Origins,” “Guyana,” “Saint Lucie,” “The Schooner Flight,” “The Fortunate Traveller,”—even the books Another Life and Midsummer considered as wholes—not to mention Omeros. Walcott’s long poems range from archipelagic to continental in size and scope. What is so thrilling about this small fry?

I take enormous pleasure in the complexity of the poem’s construction, and in how the poem’s structure is a kind of portrait of both its speaker and its author. The speaker’s explicit concern is to excoriate contemporary Trinidad in song. Walcott’s concern, from the late 70s on, is to stake a claim on literature on behalf of contemporary poets who have been told they cannot or ought not try to write poems that resonate with the past.

“The Spoiler’s Return” is a dramatic monologue in heavily-substituted iambic pentameter rhyming couplets, and its speaker, known only by versions of his sobriquet, is the ghost of a beloved calypsonian (perhaps an echo of the real-life “Mighty Spoiler” famed in Port of Spain) who passed away some years before. Its eight verse paragraphs are mainly quite short. The first five verse paragraphs comprise a twenty-line introduction, a four-line set of song lyrics, a fourteen-line mock-epic invocation, a six-line passage, most of which is borrowed from the Earl of Rochester’s “A Satyr Against Mankind,” (c.a. 1675), and a two-line refrain that recurs in the seventh verse paragraph. The sixth and seventh verse paragraphs, by far the longest at 59 and 72 lines, are satirical discourses in which “Spoils” attacks the political, economic, moral, environmental, psychological, and emotional states of Trinidad and its neighboring islands. The eighth section is a twenty-line farewell, for The Spoiler must return to a Hell quite like Trinidad. To attempt so much in a poem betrays Walcott’s fundamental values: a general recognition of verse as a capacious rather than limited form, and a particular and challenging recognition that iambic pentameter couplets remain, in the late 1970s, a flexible and contemporary medium. I find it inspiring that each verse paragraph of “The Spoiler’s Return” is so vividly accomplished and so coherent in its expression of the speaker’s character.

Yet it is the voice of The Spoiler that spoils me for other poems. In him poem construction and character construction converge: Walcott has built him out of different kinds of utterance and those different kinds of utterance complicate and enrich a polyglottal, polymodal identity. Walcott’s investment in such a complex fictional character for the expression of political content came at a time when a typical North American poet was busily “discovering (his or her) own voice,” and The Spoiler’s difference is bracing. How simple (and in their simple, supposedly expressive structures, how unintentionally cynical about verse) seem to me the speakers of so many political poems by American poets of the same period. How delicious seems to me his invocation of fellow satirists (Martial, Juvenal, Pope, Quevedo, Byron, Swift, “Maestro,” “Desperadoes,” “Commander” and “Attila”) that is itself an evocation of his song as a choral, rather than solo, performance.

The difference of The Spoiler both is and is not Walcott’s difference. Likewise, The Spoiler both is and is not Walcott. An account of the term “Calypso”—which does not appear in the poem, because it is “hidden” under a more authentic term—may help me to explain what I mean. Ethnomusicologist Errol Hill (among others) early realized that the Greek root, kaluptein, meaning “to hide,” must be a European imposition upon or a hybridization of an African term brought across the Black Atlantic by the slave trade. Thus associations of a cultural-critical calypsonian with an enchantress out of Homer or an image-cluster derived from the English word calyx, however rich to ponder, however tantalizing, are theatrical scrims we must pull aside, though we do not have to destroy them. Hill traces “calipso” (as it first appeared in print in the Port of Spain Gazette in 1900) to the late 19th century Trinidadian term caiso—the three syllables of which make it nearly homophonic with the earlier Creole kaico, “you will get no sympathy, you deserve no pity, it serves you right,” which is only a consonant shift away from Hausa kaito, “an exclamation of great feeling on hearing distressing news.” He speculates that as white auditors of caiso music slowly grew to appreciate its poignant rhythms, the term was Europeanized, mistranslated and misconstrued as the name of the island nymph who kept Odysseus captive. Both the heart-rending implications of kaito and the harsh criticality of kaico are for Walcott a living legacy still audible under the classical mask of a persona.

I wish its historical circumstances undone, I wish Walcott’s African ancestors were never stolen from their homes, but this hegemonic grafting of three languages in kaito, kaico, and calipso yields a nexus of meanings I savor when I read “The Spoiler’s Return.” For English “Calypso” acts as the screen for, hides the captive Hausa traveller “kaito” in the same way that the sobriquet of the calypsonian performer is a cover for the individual who sings in a received but flexible, polyglottal, and polymodal form. (As in the case of Odysseus, the hiding is only a detainment.) In much the same way, “The Spoiler” is a meta-name and metonym for the whole tribe of satirists, with the added coincidence (and it’s hard for me to believe that Walcott is not aware of it) that the real name of the historical calypsonian “Mighty Spoiler” was Raymond Quevedo—his last name the same as that of the great Spanish poet and satirist of the Golden Age. Walcott, who has written elsewhere, “I have Dutch, English, and nigger in me, // Either I’m a nobody, or I’m a nation,” speaks, from behind the screen-name “Spoils,” an island patois leavened by the same iambic measure that was English prosody’s best echo of the Classical measures in which Homer conjured his own screens and characters. And thus the cry of distress first heard in Africa is reconfigured and made even more resonant as the pitiless bawl of a dead, mixed-race singer, now a tourist in his own fucked-up country, an “Area of darkness with V.S. Nightfall.”

If “The Spoiler’s Return” weren’t so funny it would be a tragedy, and if it weren’t so sad it would be a silly romp, and if it weren’t so ambitious it would not feel so much bigger than its 197 lines. Certainly the decision to make an ambitious poem is no guarantee of success, but without the grain of faith upon which ambitions like Walcott’s rest, without a consciousness that art’s power is always derived from forms greater than any particular self, the question of artistic success is always reduced and sometimes foreclosed. The Spoiler says much the same thing about the oil-flush Trinidad of the ‘70s. What good is it to be so richly-endowed with resources (even if only relatively rich) if Trinidad does not raise its ethical sights? In “The Spoiler’s Return” Walcott resurrects a one-man chorus of the dead to ask English-language poets a similar question: What good is it to have so rich a heritage if poetry aims so low? The answers to such questions do not remain hidden for very long—not even for the length of “The Spoiler’s Return.”

SPENCER REECE ON ADRIENNE RICH

This week, in Madrid, the news reached me that Adrienne Rich had died. The poet Richard Blanco was visiting me, giving readings here in Granada and Madrid after a reading he had given in London. We sat in my living room with the French doors overlooking a construction site, the floors a honey-color, as I told him I’d just read on my little laptop the news of her death. There we were, two American poets in Europe, stopping to take in the news. I’ve often thought artists, and poets in particular, form their own tribe. The loss of one member is felt by the rest. He began to recite a line from one of her poems, and then recalled his love of “Twenty-One Love Poems.” Oddly, I remembered the same.

As Easter approaches here at the cathedral, crowds gather with their olive branches and flowers. You have asked me to consider a long poem and meditate on what makes a successful long poem. I pick this one. The long poem “Twenty-One Love Poems” has been with me since I was in college twenty-seven years ago. My professor, Gertrude Hughes, taught it to us in a large building from the 1800s on the Wesleyan campus there in Middletown, Connecticut. Our class was on the second floor, our chairs were wooden with desk-tops that swung up and down. Professor Hughes introduced the poem, teaching from a dark blue anthology. Many of my classmates were articulate students from New York prep schools like Dalton and Horace Mann, and so I always recall myself listening to them more than saying anything myself. The class was captivated by this poem, as I recall.

The mid-1980s was a curious time to be in college out East in America. The AIDS crisis had just been recognized in The New York Times. We never thought it would touch us. But within five years after graduation, five classmates had died. The shock of all these deaths coincided with America speaking about homosexuality frankly for the first time. Puritan America was going to have to talk about sex, and, more, talk about homosexuality. I read this poem at that time. We, as students, didn’t use the word “gay” in common discourse. Although Wesleyan has to be the most liberal leaf shining on the branches of the Ivy League, gay awareness was in its infancy. Same-gender marriages were not announced in The New York Times yet. There was still a polite avoidance of the topic.

And so this poem, with its frankness about homosexuality, made quite an impression, like someone pulling off the tablecloth on the dining room table in the middle of a meal. The poem still holds my attention. Listen to how it begins: “Whenever in this city, screens flicker/with pornography, with science-fiction vampires,/victimized hirelings bend to the lash,/we also have to walk… if simply as we walk/ through the rain soaked garbage.” The New York she is describing, the one I remember from the 80s, was not the slick version, Time Square was still dark, muggings were something you cheerfully assented to if you ventured into the subways.

Later in this first love poem, she writes, “No one has imagined us.” A phrase like this gives the poem permission to be long, I think. I have always loved that line, and it meant something to me in college. Who would I become? My journey would not be what my parents had expected. Hardships and joy all awaited me outside that small hill and cluster of brown-stone buildings at Wesleyan. Curiously, I lived in a fraternity called Eclectic of which there were only two chapters, and this odd fraternity was designed by the same man who designed the Lincoln Memorial, and, indeed, the building oddly resembled that memorial. It was as if that building was preparing us, too, for some kind of emancipation proclamation.

All is to say, this poem has stayed with me, and what sign can there be of a more successful long poem than that? In section three she writes: “Since we’re not young, weeks have to do time/for years of missing each other…./Did I ever walk the morning streets at twenty,/my limbs streaming with a purer joy?” The poem is a joyful celebration of love at middle-age, a hard-won love, against immeasurable odds. Perhaps that is why the words and lines stay lodged in my head after all this time?

I will always cherish my memories of Professor Hughes teaching this poem, how excited she was about it. I, too, was excited by it, lines like: “the maps they gave us were out of date/ by years.” The beautiful sexual frankness of the unnumbered section stays with me: “your strong tongue and slender fingers/ reaching where I had been waiting for years for you/in my rose-wet cave — whatever happens, this is.” That is it, then. Whatever happens, this is.

Rich has died. New generations have come along. The world and the culture keep changing. The Episcopal church I work in continues to change. Sometimes slowly. The Anglican communion is threatening to split over the issue of sexual orientation, in its clergy and the blessing of same-sex unions. European Episcopalians tend to be conservative. A missionary just the other day said he did not approve of gay people, believed they were a destructive force for the church and yet wanted them to come to the cathedral. Whatever happens; this is. This poem is a blessing of a same-sex union before we used those words. I sometimes think poets are the prophets of our days, for prophecy is never a tidy thing.

MICHAEL RYAN ON EMILY DICKINSON

Emily Dickinson’s Long Poem

What Whitman wanted to do in Leaves of Grass is its abundantly-stated subject: literally to “inaugurate a religion” in which he would be the new priest directing not only the cultural life but also, through his spiritual guidance, the political and social affairs of the young nation in which “every man shall be his own priest.” For this task, Whitman designed what he called a “transparent, plate-glassy style” for the democratic bible that Emerson famously praised as “the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom America has yet produced,” full of “incomparable things said incomparably well, as they must be.”

Both Whitman and Dickinson come out of Emerson, but what distinguished them from Emerson was their ability to alter poetic form to accommodate what they wanted their poems to do. Emerson pointed the way: “it is not metres, but a metre-making argument, that makes a poem– a thought so passionate and alive, that, like the spirit of a plant or an animal, it has an architecture of its own, and adorns nature with a new thing.” Emerson rendered passionate and alive thoughts in his essays— life-changing thoughts, which he generated from his journals— but he couldn’t do it in his poems and this killed them, probably because no matter how he coached himself he was unable to write poems without an inherited preconceived notion of how a poem sounds.

But Whitman was able to, and so was Dickinson. Emerson apparently never read Dickinson’s poems, although in 1857 he was an overnight guest at her brother’s house next door, and her sister-in-law Sue had copies of most of what Dickinson had written to date. Dickinson was 27. She had already begun the rigorous poetic practice and poetic project (whose ambition dwarfs Whitman’s– designedly enormous as it was) based in her remarkable understanding that poetry finds its power in truth but not truth as it can be otherwise described or articulated, much less translated into social or political discourse. This does not mean her aesthetic was privileged but only particular, and thoroughly connected to humanity by being embodied in language and the meaning language can communicate to the poet and her readers when words are arranged and discovered through the agency of poetic form.

To do this, she invented a style more radical than Whitman’s. Whitman abandoned rhyme-and-meter for the rhetoric and versification of the King James Bible and retained conventional grammar. Dickinson wrenched the rhyme-and-meter of the hymn stanza and invented a grammar based on an understanding of implication and inference beyond her time and still beyond ours. How to make poetry of the English sentence is the question answered passionately by every sentence of every real poem in English. Whitman gave us great answers, but Dickinson’s sentences are more astonishing, various, and ground-breaking than his or any other poet’s ever. Her best fifty poems are probably among the best hundred poems ever written. Do her 1789 poems taken together constitute the best long poem ever written? Depends on what you mean by the long poem.

SAM HAMILL ON THOMAS MCGRATH

When I was editing Thomas McGrath’s magnificent 400-page Letter to an Imaginary Friend, I asked Philip Levine to contribute a comment, and received this cogent response: “I hope I can someday give this country or the few poetry lovers of this country something as large, soulful, honest, and beautiful as McGrath’s great and still unappreciated epic of our mad and lyric century, Letter to an Imaginary Friend, a book from which we can draw hope and sustenance for as long as we last.”

Tom McGrath, World War II veteran of the North Pacific, was a Marxist-Leninist socialist sent into interior exile by the patriots of McCarthyism, only to spend half a lifetime working on the greatest American epic poem of the last century, a visionary work borrowing from various of our cultures and visions including the Hopi Blue Star Kachina, the tetragrammatron, biblical revelations, and the common habitat and blue collar philosophies of Midwestern farmlands. It is a work of sustained narrative like no other in our language or in our time. It is, like Pablo Neruda’s Canto General, a sublimely revolutionary work. The New York Times noted his “inspection of history from the street, an imagination imbued with facts, an uncanny grasp of the politically absurd, an appetite for mockery and affection, and a gift for describing the toils and pleasures of work.”

If there is a “great American poem,” it must be McGrath’s. There is simply nothing to which it can be compared, including Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, which, after all, is composed of poems in sequence, as are Neruda’s Canto and Ezra Pound’s Cantos. McGrath’s personal-public voice, his visionary and sustained narrative lyrical power, will endure for as long as there are poetry lovers and revolutionaries in the Americas of the future.

ERICA DAWSON ON ANTHONY HECHT

Anthony Hecht’s “The Venetian Vespers” terrified me in 2000. I still shudder in a persistent flinch. At that point, I’d never read the best kind of long poem: a poem grandly intimate; constantly turning a corner to something you think you recollect, though it smacks of a stranger’s stroke; a poem treading its space while lapping your skills of apprehension.

Something like absolute magnitude—the combination of my very young, unaided eye, and Hecht’s voice, resounding and sounding clean as a piccolo—made Hecht, too, seem terrifying. He wasn’t. I was too shy to introduce myself each of the three times I had the chance.

I had no choice but to give in to “The Venetian Vespers” stripping me down to flight or fight. The skull (belonging first to a small bat undermined by the pox in Section I, then the bone concavity of an expatriate in Section II, and, finally, the soldier’s chalice of his own brains in Section III) insisted I move. I moved through the final three sections, hoping I’d find a bone, again, while running fast from its absent eyes wholly fractured.

The skull didn’t return in that first read, or ever. Surrounded by thews of the appalling world of dreams, the vermiculated mind’s 4am, a mind scarcely coping with the world’s sufferings, looking, as if it saves itself by looking, losing but never shaking its protective shell, it keeps its head up. It warily finds ward in anything as immediate as any Venice evening, even if, like me, you’ve never been. Head high, I romanticize what was, its ruins turned memorials reminding me of the equally predictable what will be.

ROBERT PINSKY ON GEORGE GASCOIGNE

Gascoigne’s “Woodmanship” is a model long poem: completely original. Under an apparently earnest, foursquare surface, this account of a life is endlessly complicated. The last image of the slain doe’s teats—“Methinks it says, ‘Old babe, now learn to suck’”— is the climax of possibly the best ending of any long poem, and the prose dedication to his patron, who laughed at Gascoigne’s ineptitude with the bow and arrow, is possibly the best preface ever.

His way of writing about himself, neither introspective nor charismatic, remains unusual: self-celebration qualified and transformed by comedy of the self. The closest comparison for me is with Allen Ginsberg.