Robert Calafiore, interviewed by Debra Klomp Ching, about his extraordinary and colorful pinhole photographs.

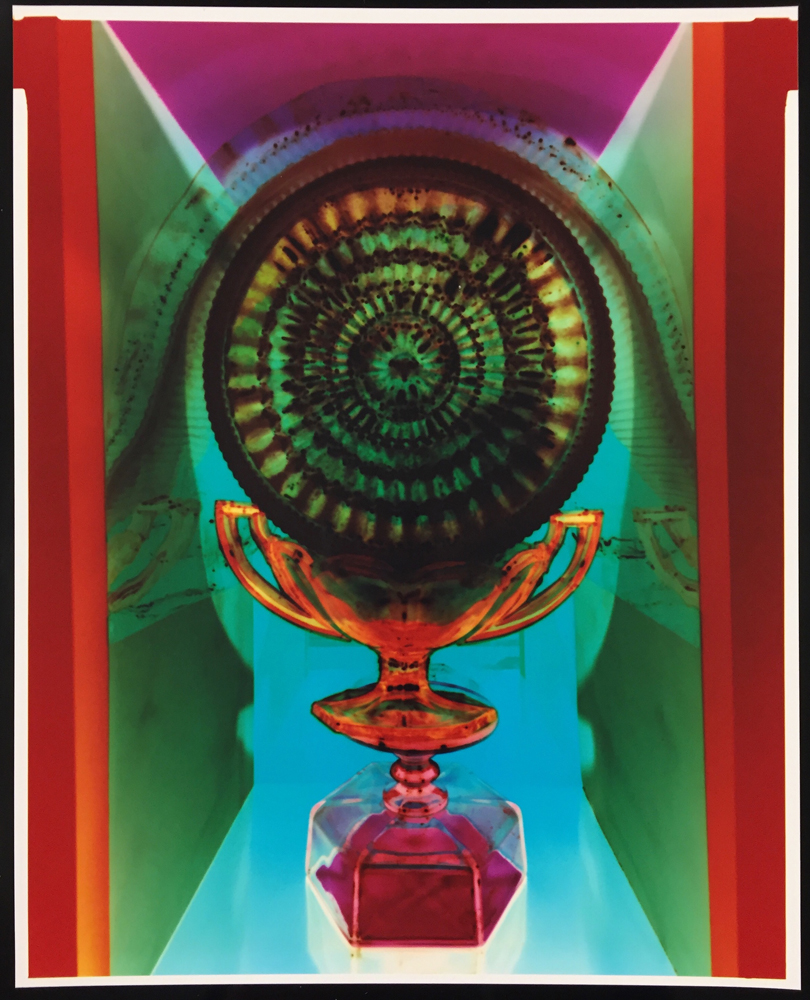

Still Life (2017-2018), 10″x8″ unique pinhole C-Type ©Robert Calafiore/courtesy ClampArt, New York

At Length: Your work was initially brought to my attention via your Instagram feed. How important is your social media presence to your creative practice?

Robert Calafiore: A very close artist friend of mine sat me down one day and said she wasn’t leaving my house until I did two things: build a website and open an Instagram account. I did both. I was excited about launching a website and worked for a few weeks to get the first version up and running. However, I was far more hesitant and nearly unwilling to begin a relationship with another social media app. I had read a great deal about the opportunities it might provide for broad exposure of my work but still had lots of questions. My friend advocated for the app and I ventured a toe in, slowly at first, and then more and more calculated as I became more savvy. What we all know now is that it can be a powerful tool. It became clear to me, after I noticed your gallery following my work, that I had to pay attention and learn how to leverage its use. That decision was one of a few pivotal moments that changed the direction of my work as an artist. Some attention had been building, but it was the first exhibition at Klompching in 2015 that made all the difference. It wouldn’t have happened the same way without Instagram.

AL: How and when did you first come to work with pinhole photography?

RC: I have been using an assignment to build a pinhole camera in my experimental photography courses for two decades. Over time, I began to notice a change in the dexterity of my students. What was once a simple project became a grueling task. The cameras were no longer light tight, there were no straight lines and the lids didn’t fit. Students were having difficulty with measuring, cutting and assembling the parts. It intrigued me and my observations of the change grew more careful and led me to study other aspects of their manual skills. I realized that their relationship to their physical world was much different than mine. The sensitivity I had to materials, objects, space and more, was missing or different in my students. I needed to spend time reviewing measurements, using a straight edge to draw and cut lines, holding a utility knife, and using tape while manipulating parts for bonding. Of course, there is now much written about our screen life. It is this shift to an experience of the world through digital life that has altered my students’ manual skills… dexterity. I was fascinated and set down a road to use the pinhole camera myself in a new project I would create around it.

Still Life (2017-2018), 10″x8″ unique pinhole C-Type ©Robert Calafiore/courtesy ClampArt, New York

AL: What was it that inspired you to work with this process? Was it particular photographers, images you had seen, or was it more to do with the process itself?

RC: It was a combination of things. The observations I was making around my students and a passion that was growing for a large collection of family glass I was hoarding came together to spark the start of a long-term project. I wanted to take working hands-on to an extreme. I decided to build my own cameras, use analog materials, make unique prints and employ the glass collection as my main subject. The piles of glass started with a few pieces my immigrant parents were first able to buy after they came to the United States in the 1940s and began building a new life. They are the face of a classic immigrant story. Arriving with nothing and working hard to raise a family, they taught us the value of labor. I watched my parents work blue-collar jobs for over 40 years. As I grew up, they also instilled in me a desire to learn and pushed me not only to work hard but to take advantage of schooling available to me, unlike them. The irony is that as a first generation American and the first in my family to go to college… I decided to major in art. Nobody really knew what that meant or where it would take me. I wanted this work to reflect on my family history, telling my personal story but also relaying some universal narratives found in objects. Objects that hold memories and drip with nostalgia. The camera’s unique perspective and ability to transform the real to a magical and extraordinary place made everything, my vision, possible.

AL: In many respects, you’re working with the most basic form of photographing—the pinhole camera. But it’s not necessarily the most straightforward or easy device to use. What have been the key challenges that you’ve needed to resolve?

RC: The extended exposures, the need for 15 to 20 thousand of watts of light, no viewfinder, and the color paper’s slow ASA were all challenges. When I first began working with the large cameras, 40″ x 30″, about 9-10 years ago, I was photographing male nudes placed in large-scale stage sets. The exposures were at least 20 minutes. The models had a hard time holding poses, and for me, creating images that satisfied what I had imagined was very difficult. On average we shot for three to four days on one set, at least 10, 12, sometimes for 15 takes to get a final image. I worked for about three years to create 20 or so pictures, learning new things every time and solving problems at every turn. Space, props, enough lighting, processing large RA4 materials and more were all obstacles but just as much inspiration too. Process and material are as integral to my work as are the ideas that drive my practice. The experimentation, the techniques and skill, all contributed to my ability to gain more knowledge about the work itself.

Untitled Figure (2008-2011), 40″x30″ unique pinhole C-Type ©Robert Calafiore/courtesy ClampArt, New York

AL: You took the unusual step of not only exposing directly to paper but exposing to color paper. Why not work with a negative and then print the results?

RC: From day one, when I saw the first print emerge from the chemicals, I was captivated. The negative image was able to see not only through and into the subject, but across it as well. It exposed something I couldn’t otherwise see. Something seemingly not meant for my human eyes. It came close to elevating the ordinary to that extraordinary place I wanted to reveal. It left me wanting more.

AL: Considering that photography is a visual art form that allows for infinite copies to be made, why is it important to you to make a unique art object?

RC: I think I have always thought about my photographs as objects themselves. And for me it was important to make each one as individual as the moments, dreams, and experiences that inspired them. No digital tools or technology are ever used. Given the choice of endless change and progress in technology available, I instead choose to use the simplest method for capturing an image, connecting more closely with my interest in understanding how technologies like augmented reality and artificial intelligence are changing our physical relationship to the world.

Still Life (2017-2018), 10″x8″ unique pinhole C-Type ©Robert Calafiore/courtesy ClampArt, New York

AL: The result of working with a positive photographic paper is that your photographs render in negative form. This produces some surprising and lushly wild color results. I wonder if you could say something about the extent to which you employ color theory, and if there are art historical figures or artifacts that have informed that part of your practice.

RC: The color is certainly one of the qualities about exposing the paper directly that I responded to immediately. It represented a lot for me but mainly my parents’ amazing life and the place from which they came. Of course, as I made more pictures, many other influences came into play. One of the most important would be Henri Matisse and his extensive work with objects in the studio. The repetitive use of objects over time, as well as the use of pattern and still life, has been inspiring. His relationship to the objects is fascinating and provided endless material, as it does for me.

AL: Between 2008 and 2011, you made a series of photographs on the human form. Can you tell me more about this project?

RC: This is how my work with the pinhole camera began. To be honest, I was unsure about what the series would become or what specific ideas would eventually emerge. I did sense that there was something there, and it excited me. These were luscious, indulgent, over-the-top, baroque, and decadent pictures that exposed my interest in the relationship between figure and environment. Influenced by art history, mythology, religion and my personal, sometimes intimate experiences with other people.

AL: Why did you change your subject so radically, from the human form to the still life?

RC: I was unsure where I was going with the figurative work. I needed some time to live with and think about the work I had made. The two subjects weren’t so different for me either. I am equally passionate about my relationship to both.

AL: Your choice of object for the still life studies is glassware. But it’s very specific isn’t it?

RC: Yes, as I mentioned earlier, this collection began with a few pieces from my parents and grew by taking pieces from everyone in my extended family and then friends. Most recently, the collection has been added to by way of purchase through flea markets, garage sales and antique shops.

Still Life (2017-2018), 10″x8″ unique pinhole C-Type ©Robert Calafiore/courtesy ClampArt, New York

AL: There’s also a wonderful abstraction—with both the form and temporality. How does this tie in to your creative and conceptual vision?

RC: I love the abstract passages that occur in the work. Though not abstract as a whole, finding the abstract moments in my work lends it some of the magical and otherworldly qualities that I seek to create. In transforming the ordinary to the extraordinary, abstraction within the pictures allows the subject to become more than it is. Hence the whole is greater than the sum of all its parts. Something new. Something iconic.

AL: You’ve said elsewhere that you make many more prints than what make the final edit. Is there a good amount of serendipity involved? Are you able to control the results more, the longer you are making the work?

RC: Yes, I have become much better at controlling results. However, I have always worked intuitively and find it important to my work to allow for surprises. Listening to the work and not getting stuck on what I had initially envisioned is critical. It still takes several tries with most set ups, but I am beginning to see some of those as variations and possibly something I can use in some way.

Untitled Figure (2008-2011), 40″x30″ unique pinhole C-Type ©Robert Calafiore/courtesy ClampArt, New York

AL: Are you continuing to work with still life—and glassware—or do you have other subjects you’ll be turning to?

RC: This summer I will return to working with the male figure. Given our current political climate and shift in cultural values, I feel like the work now has a more specific purpose. I will set out to embrace and promote our differences and provoke audiences to once again consider the benefits of those differences. And as has always been clear to me, in the end, we are more similar than different.

AL: People have really started to pay attention to you and your work. What have been the highlights for you, regarding this recognition?

RC: Wow! I still feel like I am dreaming. The most rewarding impact has been meeting so many fabulous artists, gallerists, writers, and industry experts. I have made countless new friends and connected with a whole new circle. The supporters and collectors are just wonderful. It has allowed me to continue to forge ahead with more work.

AL: Recently you exhibited at the ClampArt gallery in New York, where you’ve also attained representation. Anything else on the horizon?

RC: I am so very fortunate to have received exposure for my work. It is to be credited to many people like yourself, who offered support and opportunity over the last few years. I hope to work this summer and into early next year to finish a new body of work. Beyond the incredible relationship with ClampArt, I am working to get the work included in more reviews and critical essays as well as in front of curators who may find the work a good match for certain museum exhibitions and more.

Robert Calafiore lives and works in Connecticut, and is represented by the ClampArt Gallery in New York.