As we enter the workshop room, three girls hover in a slow-motion game of musical chairs. The movement is familiar to me. Commit to a seat too early and there may not be enough seats for your friends, or you may be stuck next to someone who talks too much, or not enough, or otherwise fails to understand—at least, in the same way that you do—the unstated, byzantine codes of teen-hood.

We’re at the Carnegie Museum of Art and have just viewed the Iris van Herpen exhibit, Transforming Fashion, which brings together seven years of van Herpen’s original haute couture. The poetry workshop is organized by Girls Write Pittsburgh, a nonprofit dedicated to empowering girls through writing. Our aim today is to write in response to van Herpen’s designs.

We sit around a long oak table surrounded by floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. The girls range from first to eleventh grade. Each says what they like to write—slam poetry, argumentative essays, short stories. One is a visual artist. Another plays the bells in the school band. It turns out the hoverers go to school together; the other four attend schools scattered across the city. They all seem focused, ready to work. The quietest one runs her fingers over her journal and looks at me, waiting for instructions.

*

I know little about fashion. My wardrobe consists of Toms, jeans, and t-shirts. I’ll focus on the poetry, I think. The words. But as I’m planning the workshop, I read up on van Herpen and become intrigued by her designs. I learn that early in her career, while interning for Alexander McQueen, she was required to do a variety of handwork, including beading and embroidery. Van Herpen says about that time, “I realized that an idea can come from a process of making. While doing handwork there, I had lots of ideas and got restless. I was dying to work for myself again. But it was really good to train myself to have that patience.”1

Van Herpen’s language about the “process of making” reminds me of being forced to write a sestina or a sonnet. As a writer and teacher, I’m continually trying to learn patience. I’m still no good at rhyming couplets, or obeying the sestina’s strict pattern of repetition, the way you have to pull out a word like a stitch again and again to come in at a cleaner angle.

*

As we enter the heavy gallery doors, our docent talks loudly, all business, and keeps waving to us, “Come closer. Closer.” Her bangs are curled under tightly, a brown inverted wave. Her posture, perfectly erect.

Down the expansive marble room stand two straight rows of bald mannequins. Each strikes the same pose—one foot an inch in front of the other, arms hanging down at the side, a slight bend at the elbow. The first collection, “Refinery Smoke,” is inspired by industrial smoke emitted by refineries. I call them the “cloud skirts.” Nutmeg brown cumulus clouds, they are made of metal gauze. A wide cloud formation hugs one mannequin’s hips. Another cloud hovers around her neighbor’s neck, obscuring her face. If you look closely, you see a fine latticework of threads, hard metal masquerading as a downy puffball.

One of the girls crosses her arms over her chest, says to her friend, “How could you sit in that skirt?”

I think of the ending of May Swenson‘s poem, “Question”:2

How will it be

to lie in the sky

without roof or door

and wind for an eyeWith cloud for shift

how will I hide?

The docent shifts her stance, and stares directly at us. “Iris van Herpen was trained as a dancer. This gives her special insight into how the body moves.” The girls seem impressed when she lists some of van Herpen’s clients: “Björk, Tilda Swinton, Lady Gaga.” She adds “Beyoncé” as an afterthought, and a few girls open their mouths and look more intently at the dresses. When asked by an interviewer, “Who buys and wears your clothes?” van Herpen responded, “People who see clothes in a different way.”

*

We move on to the “Skeleton Dress.” “Has anyone ever jumped out of a plane? Gone skydiving?” the docent asks. Nobody says anything; we just glance around at each other stiffly.

Van Herpen’s skydiving experiences inspired her “Capriole” collection. The dress that represents her racing thoughts before jumping resembles a jumble of thick black snakes. My personal nightmare, it’s a dress Björk wore with a big smile on her face. Van Herpen says of the dress, “It visualizes the extreme energy I feel during the one minute free-fall, where I become strangely aware of the inside of my body.”3

My co-workshop leader, Laurie, whispers to me, “It’s like she’s making visible the things we drag around all the time. Putting on the outside what’s inside.”

One of the girls stands in front of a black leather dress that looks like it was pushed out of a pastry bag. Black waves of icing snake up and down the A-line dress in maze patterns. She leans in close, her nose almost touching the leather.

Installation view, Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion at Carnegie Museum of Art. Photo: Bryan Conley

Installation view, Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion at Carnegie Museum of Art. Photo: Bryan Conley

Iris van Herpen, “Radiation Invasion, Dress,” September 2009, Faux leather, gold foil, cotton, and tulle, Groninger Museum, 2012.0201. Photo: Bart Oomes, No 6 Studios

The “Radiation Invasion” collection has the slick look of oil—the dresses alluring and sinister, what Bellatrix Lestrange might wear to drink her morning tea. The designs are based on the radiation that surrounds us, alpha, beta, gamma, x-ray, and neutron waves. Van Herpen imagined what would happen if we could manipulate these waves in the future. “What if our bodies could attract and repel as living magnets?” reads the description I find online.

One of these dresses has a mask that covers the mannequin’s face with silver leather interlaced into a stack of shimmering V shapes. “The dresses are made for model’s bodies. Very slim,” says the docent. I wonder how the girls register this comment. Their faces are impassive.

*

How to say in language what van Herpen’s dresses do? I can feel my words touching the textures and shapes of her dresses, but the whole of them make an experience words can grope, but fail to hold. For me, each dress functions the way a poem does: “A poem should not mean / But be.”4

Van Herpen allows the material she’s working with to help dictate the form. “It’s my direct action with the material that often is my design process,” she says. “Each technique and each material asks for another approach and process, and that’s what challenges me, to find new ways of thinking and doing.”5

For writers, words are our sole material. But in the process of ekphrasis, a verbal description of a visual work of art, the visual can be a springboard to new language. Ekphrasis creates something separate but connected, not entirely a new thing, but one charged with the force of the new.

Art can give us a new space to move our thoughts around in, an unfamiliar space in which to imagine standing. It’s especially necessary for young people. I remember my own teenage years—the sudden feeling of options narrowing. I wouldn’t be an Olympic soccer player, or an astronaut. Walls rising up around me. Those walls already felt gendered: I could like sports but should also be pretty; I could be smart, but not outspoken. Some things made me feel free: books, music, nature, art. Art offers us permission to expand. To be uncontainable.

*

Van Herpen’s work, which is in a form that is at least imagined as capable of containing people, feels colossal. It reaches beyond—not only language, but also our usual understanding of physical reality, what the materials of our world can do.

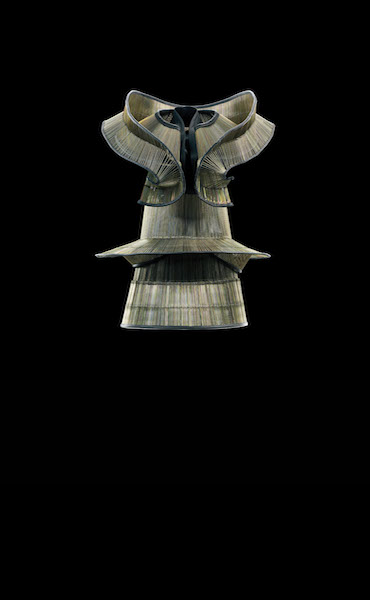

To make the “Chemical Crows” collection, van Herpen and her team took apart 700 children’s umbrellas. I’m drawn to a dress that has wings made of brass umbrella ribs arcing above the shoulders. I want to run my fingers over each brass rib.

Iris van Herpen, “Chemical Crows,” Dress, Collar, January 2008, Ribs of children’s umbrellas and cow leather, Groninger Museum, 2012.0192.a-b. Photo: Bart Oomes, No 6 Studios

Installation view, Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion at Carnegie Museum of Art. Photo: Bryan Conley

One dress has hundreds of ribs fanning out in a tall, regal collar. I’d like to wear it on a day when I don’t want to talk to anyone. A few of the girls whisper something about warriors. I hear them saying, “Cool, cool.”

*

Van Herpen’s “Bird Dress” has seagull skulls nested in it, made to look like live birds, with fierce eyes and open mouths. One looks about to bite the mannequin’s pallid neck. Some girls seem impressed by this fact, others grossed out. Van Herpen said of this dress, “There are 3 birds that are fighting together and trying to fly off. The dragon-skin feathers move completely differently from normal feathers. They vibrate in all directions when you wear the dress, which creates a strange optical illusion when looking at the birds in motion. I tried to visualize the surreal movement between man and nature here. The dress looks technical, but is completely handmade.”6

My favorite dress looks like an organ in a European cathedral, and also like something Artemis would wear on the hunt. It’s made of magiflex, a plastic used in the sign industry—the dress is at once rigid, intricate, and earthy. I hover near it awhile, wishing I could try it on. Maybe I wore this dress in another life.

My notes tumble into a list of oppositions that later seem beside the point: technical/handmade; soft/hard; wood/plastic; process/product; utility/beauty.

*

In the workshop room after viewing the exhibit, we ask the girls to take a few minutes and look through their notes.

“What words or thoughts interest you? Underline them if you want,” I say.

Someone asks, “What is the point of creating clothes that aren’t accessible to real, everyday people?”

“It’s about expression and experimenting.”

Another girl says, “Yeah, it’s fashion as an art form.”

“But why can’t she make it more open for normal people to wear?”

I thought the girls would be interested in writing into their imaginations—naming superpowers, or science fiction flights of fancy—instead of wanting something for normal people to wear. I think of my eleventh-grade English teacher, Dr. Brozick, standing at the chalkboard next to the scrawled question, “What is normal?” He had nipple rings that poked through his shirt, and supposedly rode his motorcycle cross-country to go whale watching in California every summer. I loved him and I feared him.

I can’t remember anything more than the question—and what it did to me. It was the first time I saw that word. “Normal.” I started looking at people differently, wondering why I bought clothes at the Gap, or hadn’t dyed my hair green. But I think by the word “normal” the girls mean a dress they can wear in everyday life. Something that is of use.

Gaga and van Herpen would agree that there is no normal. Yet the dominant tide of our culture still pulls us all toward a milquetoast middle ground.

Marianne Moore argues that in poetry, we find:7

Hands that can grasp, eyes

that can dilate, hair that can rise

if it must, these things are important not because ahigh-sounding interpretation can be put upon them but because

they are

useful; when they become so derivative as to become

unintelligible, the

same thing may be said for all of us—that we

do not admire what

we cannot understand.

Van Herpen would have us live in Moore’s “imaginary gardens with real toads in them.” And, I think this is what the girls want: some sense of a colossal world in which the ordinary can also live, as well as the reverse—the colossal in the everyday.

Installation views, Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion at Carnegie Museum of Art. Photo: Bryan Conley

Our first writing prompt uses the beginning of Lucille Clifton’s poem “it was a dream.”8

in which my greater self

rose up before me

accusing me of my life

The handout reads, “What does your greater self or fiercer self look like, sound like, act like? What does she say?”

Like the girls interrogating van Herpen’s dresses, I sometimes wonder, what is the use of art and poetry, of one workshop on a Sunday afternoon in April?

We write for a while to the prompt, and share with the person next to us. The girl next to me shares her poem. I have to lean in to hear her voice. She reads about how her best self, her fiercest self, walks down the street with pride. Holds her head high. It’s a concise, powerful lyric poem. She’s only in seventh grade. But she doesn’t leave her contact email, so I can’t reach out to ask for the poem. I keep trying to remember the words. I can see them in neat printing on the lined page of her journal.

*

I wish I’d had a workshop like this when I was their age. I was writing alone, not sharing with anyone. It took me twenty years to write a poem about being harassed by the boy who sat behind me in eighth grade homeroom. He would lean up every morning and whisper things in my ear while I was trying to finish my homework. Things like, “You have such a nice ass” or “I know you’re actually a slut.” My spine froze. I pretended I didn’t hear him. I wish I had been able to write about it and share it with someone who might have understood. I wish I could have imagined being protected by the Artemis dress. His knife-like words bouncing off my body like tiny leaves.

*

One of the older girls, Sophie, shares her poem. We all listen, then comment on parts we liked. One of the girls says, “I liked how you said you felt inhuman. That felt powerful to me.”

Sophie later says she’d love for me to include it in my essay. Here’s an excerpt:

Freedom

I’ve always felt like I don’t belong.

I’m not referring to feeling isolated from people. I’m not referencing the idea of being a unique and “weird” individual. What I am trying to convey is much less earthly and far darker than anything human.

I feel inhuman.

I feel like my body is not mine at all. I feel like an outsider in this sphere that we call our world. I feel like I am not a person. I truly feel like life was not meant for me.

And I’ve felt this way since I had the ability to form and remember thoughts.

I feel like I’m an invisible gas just floating about, with nothing but thoughts to call my own.

But I AM human. I DO live in a body. It’s mine. I have eyes and a brain and muscles and skin. I live and experience the earthly life.

—Sophie Williams

We’re out of time, so we give the girls a prompt to take with them: Pretend you are writing a letter to yourself. What do you want to say? You might think about the van Herpen dress you found most striking. What about it compels you? What makes you feel free?

If you get stuck, try what Jan Beatty does in her poem, “I’ll Write the Girl.” Name what you’ll never write, then write what you will.9

The thing I’ll never write is the green leaf

with its rubbery-hard veins, I’ll never

write the structure exposed, insteadI’ll write the girl picking it up, green leaf,

her pudgy hand & her wanting it, that’s it

—–

Emily Mohn-Slate‘s recent work is forthcoming or has appeared in New Ohio Review, Crab Orchard Review, Indiana Review, Tupelo Quarterly, Poet Lore, and elsewhere. Her manuscript, The Falls, was a finalist for the 2016 Agnes Lynch Starrett Prize offered by University of Pittsburgh Press, and the 2017 Blue Light Book Prize offered by Indiana University Press/Indiana Review. She teaches creative writing at Chatham University and lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

—–

1. Alice Gregory, “Iris Van Herpen’s Intelligent Design,” The New York Times Style Magazine, April 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/08/t-magazine/iris-van-herpen-designer-interview.html.↩

2. May Swenson, “Question,” Nature: Poems Old and New (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1994).↩

3. Liz Stinson, “Iris van Herpen’s Extraordinary Clothes Are More Like Wearable Sculptures,” Wired, November 2015, https://www.wired.com/2015/11/iris-van-herpens-extraordinary-clothes-are-more-like-wearable-sculptures/.↩

4. Archibald MacLeish, “Ars Poetica,” Collected Poems 1917-1952 (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1952).↩

5. Stinson, “Iris van Herpen’s Extraordinary Clothes Are More Like Wearable Sculptures.”↩

6. Stinson, “Iris van Herpen’s Extraordinary Clothes Are More Like Wearable Sculptures.”↩

7. Marianne Moore, “Poetry,” Others for 1919: An Anthology of the New Verse, edited by Alfred Kreymborg (New York: N.L. Brown, 1920).↩

8. Lucille Clifton, “it was a dream,” The Book of Light (Copper Canyon Press, 1992).↩

9. Jan Beatty, “I’ll Write the Girl,” Red Sugar (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2008).↩

—–

Exhibition Credits, from Carnegie Museum of Art website. Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion was co-organized by the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, and the Groninger Museum, the Netherlands. The exhibition was curated by Sarah Schleuning, High Museum of Art, and Mark Wilson and Sue-an van der Zijpp, Groninger Museum. Support for this exhibition has generously been provided by Creative Industries Fund NL.